Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Seashore Village (1965) Film Review

The Seashore Village

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

For all that human cultures vary around the world, there are certain features that have more to do with environment than location. Every coastal settlement, every fishing community has legends and songs about men lost at sea, about widows who spend their lives watching the shore and waiting for them to come back. In every such settlement there are rituals, prayers, superstitions meant to keep the men safe, to bring them back. The Seashore Village is based in such a place, in a remote corner of Korea by the East Sea, where great store is set by dreams and omens. The trouble is that bad dreams about boats sinking are hardly a rarity, and sometimes the boats have to go out anyway, and when the sky darkens there is nothing for the women to do but beg the gods for mercy.

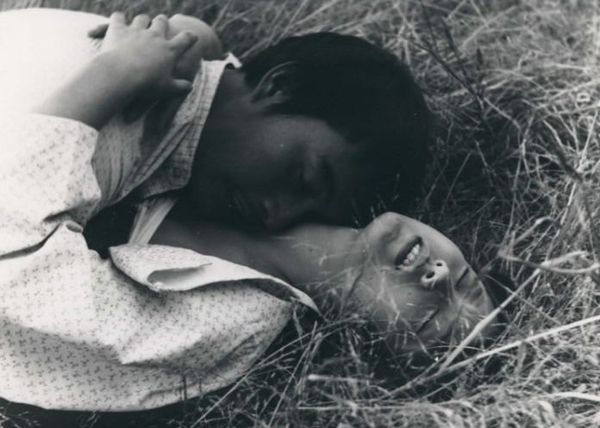

The heroine of this film, Hae-soon (Ko Eun-ah), has been married for just ten days when she loses her beloved husband to the sea. Continuing to live with his mother and his protective brother, she is thrust into a new way of life, joining a community of widows and diving for sea urchins in order to earn a meagre living, but her youth and beauty mean she faces constant pressure to get involved with another man. When drifter Sang-soo (Shin Young-kyun) takes an interest in her, she desperately tries to get him to leave her alone. His refusal to listen propels them both into a dangerous life, in which an onslaught of conflicting emotions and overwhelming experiences erode her sanity like waves beating up against the shore.

In its time, the Seashore Village was presented to viewers as a stirring tale of doomed romance. Most modern audiences will experience it very differently. Sang-soo's pursuit of the lonely young widow includes several attempts at violent rape before he he finds another way to compel her to succumb to his advances. Her subsequent expressions of desire for him can be read either as an unrealistic and disturbing male fantasy pasted into the story or as the first overt expression of her surrender to madness, a self-destructive impulse paralleled by the desperate actions of another woman who has lost her husband to the same storm. She seems to be condemned to suffer by her beauty, which makes women envious and sees several men assault her; without a man in her life she has no protection, no social recourse, so she might as well surrender to this one as to others.

Throughout, director Kim Soo-yong shows her drawn towards water - the sea, a mountain lake, a deep well. We see her caught in a storm; we see her weeping when her brother-in-law is told the he may not. There's a sense that she finds a connection in the water to her lost love, something that miner Sang-soo can never understand, but also that this is her nature as a saltwater girl and a truer expression of her desires. Though the film was made in 1965 when Korea was still very conservative, it deals extensively with female desire, something the widows are free to discuss as girls and married women could not, and there are even lesbian scenes the likes of which later Korean films would struggle to get past the censors. The rich and complicated lives that the woman experience within their community challenge then prevailing notions about widows. these scenes provide a rare early opportunity to glimpse women's lives in the absence of men.

The film is held together by Ko's heartbreaking central performance and by Jeon Jo-myeong's magnificent cinematography. Even though time has not been kind to the original print, there's a remarkable beauty to the landscapes it depicts, something that is essential to understanding Hae-soon's compulsions and her sense of self. Strengthening the sense of place are extensive scenes of the villagers at work, which also give the film an ethnographic quality. It's a testament to Kim's skill that these are always compelling to watch and never feel like padding. The action moves along more quickly than in many contemporary Korean works and throughout there's a sense that the characters are haunted by that initial tragedy - that it has not yet come to its conclusion and that, sooner or later, it will happen again. Yet as Hae-soon's mother-in-law (brilliantly played by Hwang Jung-soon) observes, who could bear to leave the sound of the waves?

Reviewed on: 21 Oct 2019