Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Taking (2021) Film Review

The Taking

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Between the 1780s and 1880s, the frontier of what would become the US pushed westward from Virginia to Oregon and then south into California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. It traversed thickly forested valleys, snow-capped mountains, thundering rivers and hundreds upon hundreds of miles of broad, grassy plains. In the popular imagination, however, these diverse landscapes frequently converge into one: the red, dusty desert and towering wind-carved buttes of Monument Valley.

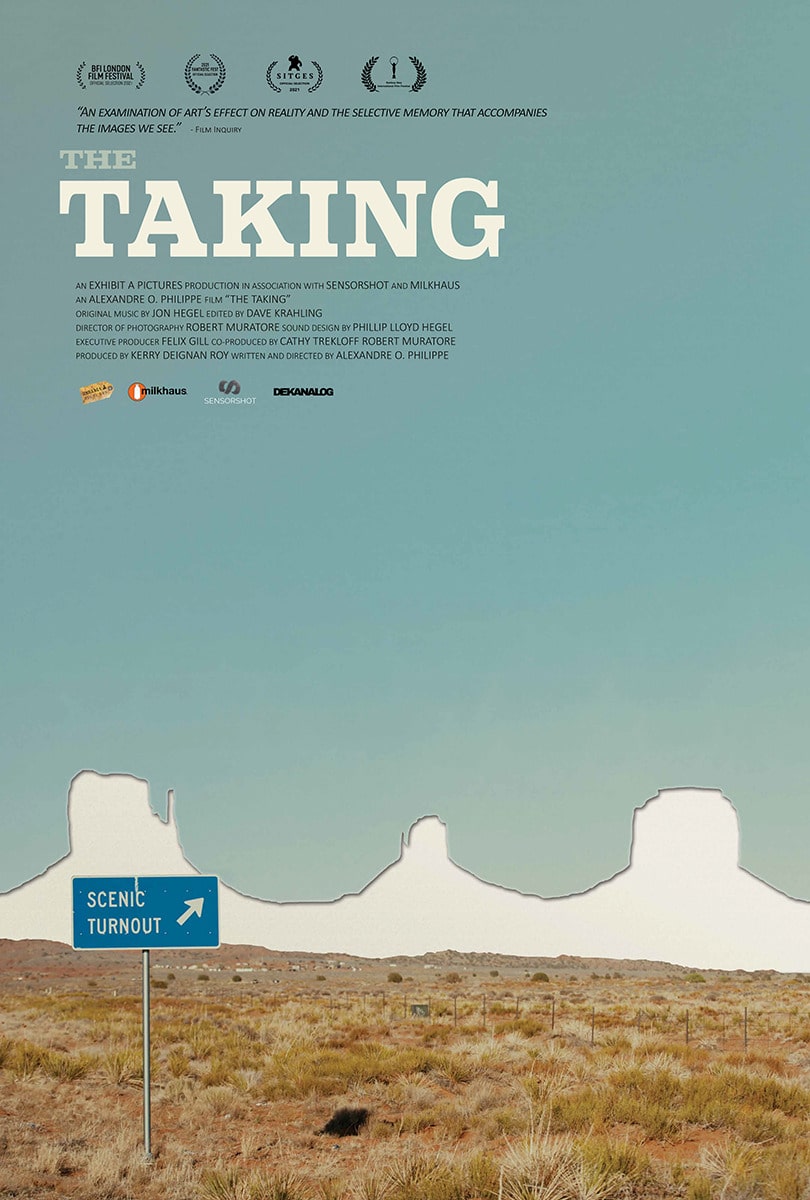

There are, in fact, several Monument Valleys scattered across the US. This documentary is concerned with the one known as Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii to the Navajo people in whose nation it stands, astride the state line between Utah and Arizona, on the Colorado Plateau. It’s a place which cannot help but make an impression. As director Alexandre O Philippe notes, the writer Willa Cather called it ‘God’s unfinished construction site.’ It is a place full of memory and tradition for its indigenous inhabitants, making it very hard for them to leave, even though staying has forced them to endure desperate poverty for generations. To most outsiders, however, it is indelibly associated with the films of John Ford.

Moulding an assortment of refugees and opportunists from traditionally antagonistic backgrounds into a new nation in just three centuries is no easy task, and the legacy of Hollywood (in partnership with pulp literature) as a purveyor of easy-access foundational myths is too often overlooked. Philippe approaches it here with mingled admiration and horror. The latter, of course, because it required covering up genocide and creating a new version of history in which innocent white settlers in an unused land were attacked for no reason by bands of savages and relied on brave vigilantes for their salvation. The former because Ford’s work is stunning, its appropriation and reinvention of sacred Navajo territory some of the most impressively crafted and effective propaganda in history.

His technique is analysed in detail here, going back to his childhood in Connemara and the impact of growing up in a landscape which towered over anything human beings could construct. His art, Philippe suggests, grew from understanding the quintessential American to be a lone outsider, always on the move in a strange land; and recognising that the journey west represented an inner journey still going on today. The iconic geology of the valley is transformed through his work to become symbolic of the trauma of migration and conflict. Philippe reflects on the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Capitol building as similar symbolic acts, engaging with key features of the US landscape as a means of trying to reshape what they represent.

The trauma created by such acts for those invested in the original symbolism can be considerable. Though there are not many Native voices in this film, they come through clearly. Adding to the suffering caused by the appropriation of sacred land and the new history Ford created was the fact that many Navajo and Apache people themselves participated in the films, dressing up in skins and feather headdresses and whooping as they road horses, pretending to belong to any number of different tribes. Ford paid them, however, and in hard times, their livestock having been confiscated by the US government, they had little choice.

Today, the myth is perpetuated through tourism. Visitors often ask, we are told, where the tall cacti are, having seen them in the films. They don’t exist. Ford simply planted them as required to add an extra bit of visual interest. He also added, at various times, cows, towns, tepees, even a railroad – all laughable to those living locally, though ultimately no sillier than having this same stretch of land stand in for Dakota, Oklahoma, Arizona, Nebraska and even Texas. Of course, people believed it all. They saw it on the screen.

We see smiling visitors take photographs of one another with the famous landscape in the background. White people taking ownership of brown people’s spaces, Philippe reflects – perpetuating white ways of seeing whilst brown people’s stories go unheard. And yet here, too, the silence echoes. Where are those other stories? The quietness of the landscape itself speaks to the genocide. Philippe could have presented us with some of those narratives but others are irrevocably lost. The old symbolism is faded, overwhelmed. As white people at last begin to question what replaced it, the symbols remain, aloof, looking on, a reminder of the small and fleeting nature of all of us.

Philippe’s incisive, forthright approach leaves no room for apologism. He admires Ford’s films like a he admires the desert, recognising their lack of mercy. This information-dense film demands a lot from the viewer, but it has a lot to give. It invites viewers to look at every landscape with fresh eyes.

Reviewed on: 03 May 2023