Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) Film Review

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Reviewed by: Anton Bitel

"You have nothing to worry about. You just take it easy now."

It may sound blandly reassuring, but there have been few utterances more misleading than this one at the very centre of Tobe Hooper's classic of southern discomfort. Even before it spawned sequels, remakes and a thousand imitators, Hooper's original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was already three distinct films at once: the expected shocker evoked by the title and by the film's near-instant notoriety; the masterwork of visual restraint (coupled with unhinged tension) that Hooper actually made; and the no-holds-barred gorefest that Hooper magically gets viewers to imagine that they have seen.

It is a status perhaps best summarised by the film's long and unhappy history with ratings boards and censors. It might seem unimaginable now, but when Hooper was making his ultra-low-budget film, commercial considerations led him to consult closely with the MPAA, his intention being to produce a horror film that would meet all the criteria for a PG rating in the US. The result is a movie where unspeakably unpleasant acts tend to take place out of shot, and are conjured more by atmosphere and suggestion than by any voyeuristic explicitness.

So successful, however, was Hooper in prodding and pounding the imagination that viewers would take away from the film far more than they had ever actually witnessed. When James Ferman, then director of the BBFC, announced that he was going to ban the film (indeed, it would remain unavailable legally in the UK, apart from brief screenings within the Greater London Council, until Ferman's departure in 1999), he also made it clear that he would not be dissuaded from his decision by the filmmaker's removal of any particular scene or scenes. Rather, what caused Ferman such concern was something irreducibly, indefinably disturbing about the film's totality. Of course, in terms of horror, there can be no higher praise for Hooper's art.

In its skeletal outline, the plot is incredibly simple, and in fact clearly forecast in the po-faced voice-over by John Larroquette with which the film opens. This is to be "an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her disabled brother, Franklin", who "could not have expected nor would they have wished to see as much of the mad and macabre as they were to see that day", when "an idyllic summer afternoon drive became a nightmare", leading to "the discovery of one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history." Yet if the terrifying misadventures of young co-eds in collision with a group of insane and murderous rednecks sounds like an overfamiliar premise, that is only because of the many, mostly inferior horror films that have subsequently picked every last vestige of flesh off TCM's bones – and in any case, with Hooper's original the devil is all in the details.

For a start, there is that introductory voice-over, claiming authenticity for events that never actually took place, and convincing many a gullible viewer, like any good campfire tale, that Leatherface and his kin might still be out there. True, one or two background details (the grave-robbing, the furniture and costumes fashioned out of human remains) have been borrowed from the real-life story of Wisconsin killer Ed Gein (who also loosely inspired Hitchcock's Psycho and 'Buffalo Bill' from The Silence of the Lambs). However, Hooper and co-writer Kim Henkel's mad family of cannabalistic Texan ex-slaughtermen is entirely their own invention, while the expressly stated date of the film's events, 18 August 1973, is linked to "the annals of American history" only in being a few days AFTER the film's production shoot ended.

Then there is the film's palpable sense of claustrophobic dread, achieved through the perfect storm of Daniel Pearl's eerie mobile camerawork, Bob Burns' surreal sets and props (all skin, bone and feathers), and the unnerving concrète score composed by Hooper and Wayne Bell. All these elements set the stage for some of the most prolonged scenes of sustained panic ever captured by cinema, as Hooper infects characters and viewers alike with the thrill of a madness from which there can be no real escape.

This film may be forever associated in the popular imagination with the sound of a humming chainsaw, but far more pervasive, and far more distressing, are the piercing, near constant screams of Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) - arguably cinema's first 'final girl' – as she is repeatedly subjected to bludgeoning psychological and physical trauma by her hungry captors, gathered round a dining table in the film's unbearably protracted final third. This sequence has often been imitated, but no other film, apart from Eraserhead (1977) with its memorable 'manmade' chicken scene, has managed to match it for sheer domestic delirium and shrill hysteria.

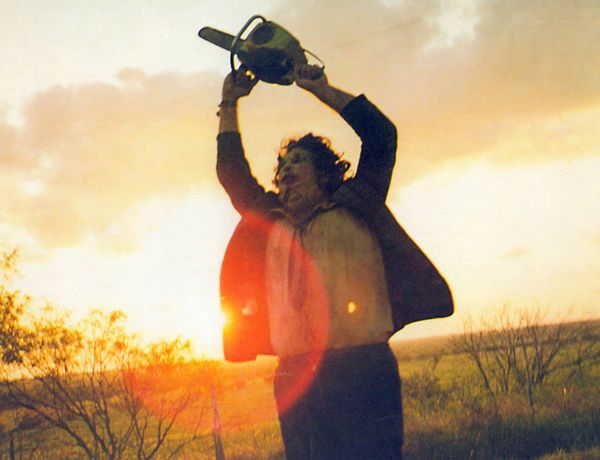

Adding to the unease is the film's refusal to pander to what we now call 'political correctness'. The chief killer here (Gunnar Hansen), called Leatherface because of his penchant for wearing masks made from the faces of his human victims, utters inarticulate gibberish and is clearly mentally retarded, while, conversely, little attempt is made to cast Sally's wheelchair-user brother Franklin (Paul A Partain) in any sympathetic light. Indeed, so persistent is Franklin's irritant, although understandable, whining that his eventual demise (in fact, the only death by chainsaw in the entire film) has been known to draw cheers from audiences. Uncomfortable, indeed – although none of the five young travellers wins our sympathies for anything other than their harrowing circumstances, and Sally, who is the most overtly annoyed by her brother, will in the end have been given her own taste, along with the audience, of what it is like to be stuck in a chair, immobile, terrified and helpless.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre may be a relentlessly agonising visceral experience that batters its viewers into submission, but it is also at times darkly funny – and in a way that only enhances the horror's special brand of derangement. For all its backwardness and homicidal tendencies, Hooper's cannibalistic family holds up an absurd mirror to domestic dysfunction of a more everyday variety. There is something immediately recognisable in the grandfather (a heavily made-up John Dugan), so ancient that he can no longer speak or act for himself, and in his three endlessly bickering grandsons - the eldest (Jim Siedow) always trying to keep the others in line, the youngest (played by a manic Edwin Neal) branching out as an aspiring artist (using corpses as his medium), while Leatherface just stays at home doing the housework (and butchering).

From our very first glimpse of him as a hulking monster with a slaughterhouse hammer raised for the kill above his hideous facemask, Leatherface cuts a terrifyingly implacable figure, and it is hardly surprising that he has become such an icon of horror – yet this image of carnal, masculine ferocity is undermined somewhat when he is later seen fussing around the kitchen in a feminine 'wig' and floral apron. In a household where there are no women (or at least no living ones), the merciless mass-murderer Leatherface has apparently also assumed the role of mother. It is shocking and grotesque, but also undeniably comic, to see in this crew of sickos something that resembles aspects of every family – and to realise that it is they who are the victims of home invasion here.

So The Texas Chain Saw Massacre both is, and is not, what its reputation would have you believe. It is not at all gory, not at all graphic – hell, it does not even feature a chainsaw massacre – and yet, for all that, it remains to this day a punishing assault on the senses, drifting from initial disquiet and foreboding to something altogether more off the hook. It is a special dish from the deep south, once tasted, never forgotten – and now, at a time when once again there is a Texan family dynasty running a deadly campaign of shock and awe against any perceived outside threat, Hooper's redneck-fearing mythology has never seemed more relevant.

Reviewed on: 06 Nov 2008