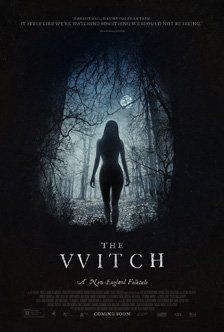

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Witch (2015) Film Review

The Witch

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

Religion, Grimm-style fairy tales and superstition mingle with sexual awakenings and the overwhelmingly harsh realities of early US colonisation in Robert Eggers' assured debut, which shows - just as The Babadook did last year - that imagined monsters can still be deadly.

America in the mid-17th century is a place where all you have are your wits and your family - and when Red Riding Hood scampers through the forest, it doesn't necessarily mean you're set for a happily ever after. For Yorkshireman William (Ralph Ineson) and his family, things are tougher than most, as they have been ostracised from their settlement on religious grounds. The family is devout and the reason for the banishment never spelled out but it is an early indication of the sort of societal schisms that would result, later in the century, in the Salem witch trials. An early shot showing the family's rickety wagon exiting the gates of the town has a balanced grace that is a hallmark of the film, conveying a wealth of information in a single moment.

The family's new homestead is marked by isolation on the fringes of a forest, with the children strictly forbidden to go in. Eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya-Taylor Joy) is tasked with looking after her younger siblings, which is easier said than done. Her younger brother Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw) is devout and thoughtful but, as lingering camera shots of Thomasin's bodice tell us, sinful thoughts come to the best of us. Meanwhile twins, Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson) are partners in crime, scampering mischievously round the farm singing songs about the family's Billy goat, portentously named Black Phillip. Then one day, Thomasin takes baby Samuel to the brook and he vanishes in the middle of a game.

We witness a possible gruesome fate of Samuel - but now we are dwelling in the emotional landscape of the family, so this could be satanic fact or just a manifestation of their deepest fears.

After the disappearance, things begin to unhinge. Mum Katherine (Kate Dickie), prays and cries in equal measure, breaking off only to berate Thomasin whom she blames for Samuel's loss. William, meanwhile, is soon contemplating his own sins of pride and omission. The children feed on the fears of their parents, listening at night to the talk downstairs, the possibility of burning in hell as real as a the spectre of starvation from a failed harvest. As the psychological and religious framework of the family begins to break down, the supernatural increasingly manifests itself. A hare staring in the woods or frightening the goats at night becomes less a part of the natural order than something malevolent waiting to feed. "We will conquer this wilderness," says William. "It will not consume us." But perhaps the family have more to fear from themselves.

Eggers draws fully on the iconography of the period, the muted greys and greens of the landscape captured by cinematographer Jarin Blaschke broken only by repeated flashes of cardinal red, bringing with it the suggestion of cardinal sin. Several candlelight scenes recall the work of the 17th century masters, such as Caravaggio, with William frequently presented in Christ-like poses. Mark Korven's music also draws heavily on religious themes extending them discordantly and even incorporating sounds from the farm, such as the goats, as part of his 'orchestra'. The cast are a powerful unit, from Ineson's gruff stoicism to Dickie's bottled up resentments and Scrimshaw's bright openness, which we see cloud over when he considers his lack of baptism. He and Taylor-Joy, who brings a mixture of vulnerability and quiet determination to Thomasin, are names to look out for in future.

Beyond its considerations of the evil that men do in the name of religion, Eggers' film could also been seen as an origins story for some of horror's favourite devices - witches in the wood, goats as the shape-shifted devil and the shared connection of twins as something to be wary of. But though Eggers nudges us to remember the irrationality of our fears, he carefully stokes them at the same time as the family falls apart, sucking us into a world where the devil may ride out whether you believe in him or not.

All the while, Thomasin, the only one of her family to fully vocalise uncertainty and recognise hypocrisy at the heart of their home, could be the witch of the title or a victim of belief in a God who must, by definition, have an evil opposite. Faith can be fatal.

Reviewed on: 25 Jan 2015