Eye For Film >> Movies >> Tigers (2020) Film Review

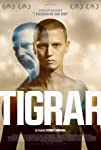

Tigers

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Martin Bengtsson was just 15 years old when he was first signed by a professional football club, Sweden’s Örebro SK. Two years later he was snapped up by Inter Milan. It seemed like a dream come true, but as Bengtsson went on to reveal in his autobiography, it was anything but. This film by fellow Swede Ronnie Sandahl dramatises his story, with a powerful central performance by Erik Enge as the brilliantly talented young man who is hopelessly out of his depth.

Sweden’s official submission to the 2022 Oscars, Tigers – a title which will make complete sense when you watch it – picks up when Martin is first invited to join the Italian club. There’s a medical, naturally, but the dehumanising nature of it as presented here is the first clue that this might not be a conventional sports film. Martin is paraded around half-naked in front of much older men in suits who discuss him in a language he doesn’t understand and make notes. His teeth are examined as if they were buying a horse. In a later scene, we will see him fall on the pitch, get his leg sprayed by a physiotherapist and limp back to his feet under the watchful gaze of his employers. There is no human sympathy there.

As any ordinary youngster would be, Martin is dazzled by the scope and meaning of what is happening in his life, as well as by the sheer strangeness of the world in which he has found himself. En-route to the players’ house, he sits in the back of an expensive car eating an egg, looking newly-hatched himself. He’s lean, with a wiry physicality, yet there’s a certain fragility about him. he has made only one request – that he have a room of his own – and yet this is denied to him. it’s a mix-up, they say. It will get fixed. Of course, it never does. it is very difficult for the shy teenager to get any time alone, and over time it becomes apparent that his new masters know exactly what they’re doing to him.

Competitive sport always involves pressure, and talented young people are very vulnerable. If you watched one of 2021’s other hit sports films, King Richard, and wondered why Venus and Serena’s father risked so much to protect them, this film neatly sums up what he wanted to protect them from. Although it was conceived beforehand, it has taken on new meaning in the wake of the #MeToo movement, especially as that movement has expanded to acknowledge abuses against men and the fact that abuse can take non-sexual forms and still be seriously damaging.

Martin’s famous talent means that he faces bullying from the moment of his arrival. His initial inability to speak Italian makes it difficult for him to defend himself or make friends. He is put through rigorous physical training, which he is happy enough about, but then gets no opportunity to relax. Any time spent outside the bounds of the house is severely restricted. At one point the team visits a nightclub, but Martin is not interested in the casual hook-ups with fans that his teammates engage in. he desperately needs a point of human contact, and when he manages to meet a girl, another Swede, who might be able to offer that, the reaction of his bosses is not exactly positive. At every stage he is subjected to measures of physical or psychological control which would exhaust the resources of most fully grown adults and seem impossible for a teenager to overcome.

Seen through this lens, the familiar excesses of young footballers might be interpreted differently. Martin doesn’t really know what to do with his money, having no opportunity to spend it in a normal way, so he splashes out on a sports car which he’s still too young to legally drive. This leads to a brief respite from all those claustrophobic interior scenes, and we get a glimpse of who Martin really is, or could be. The simple joy he finds in going fast, and in the glamour of the car, highlight the ways in which he’s still just a child. The contrast which this presents with the rest of the film brings his depression into sharp relief and also demonstrates how unnecessary it is. The idea seems to be to let him expel all his pent-up emotion on the pitch, but in the process he loses sight of the joy which football used to bring him.

In the footballing scenes, which are relatively scarce, Sandahl adopts an unfamiliar perspective. He takes the camera in close, often focusing just on the feet, so we see that talent, that machine, detached from Martin’s humanity. We also see the pitch as Martin sees it, a vast space unnaturally lit beneath a vast dark sky. It’s a lonely space, with teammates, and the ball, far away for most of the duration of a match. When Martin demonstrates his talent (cut to archive footage) he is celebrated, but what Sandahl is interested in is the weight of all this other experience which fans don’t normally see.

Inter Milan have admitted, now, that that was a problem with what happened to Martin, and they cooperated in the making of this film. What really gives it weight, however, is the near certainty that there are other young athletes out there going through similar experiences right now, in sporting institutions around the world. Meanwhile, sports scientists are increasingly of the opinion that it is not the only way to bring out their potential. Tigers is a tough film to watch, immersive viewers in Martin’s pain, but it is also, in the end, a testament to his courage. Trapped in that space, he spirals into self-destructive rage and finds himself in increasing danger. It takes a different kind of brilliance to find a way out.

Tigers is in UK cinemas from 3 June, and will be screening at the Glasgow Film Festival on 10 March.

Reviewed on: 20 Dec 2021