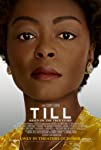

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Till (2022) Film Review

Till

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

For African Americans, and for anybody who studies the history of race relations in the US, the name Emmet Till carries a special charge. It conjures up the face of a 14-year-old boy who was murdered in horrific circumstances for reasons which most people will find hard to comprehend. The killing is remembered in numerous poems, songs, books and plays, and the facts surrounding it have been the subject of several documentaries, but this is the first big screen feature film to explore it in dramatic form. In doing so, it asks a key question: why, when so many other Black people were lynched in the Deep South, is it Till whom we remember most clearly?

That question is an important one because the legacy of the case led to major cultural changes, and eventually – in the year this film was made – to a legal one. It is widely attributed to the actions of the murdered teenager’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, and accordingly this film focuses on each of them in turn. Beginning with them together in Chicago creates the sense of a reality not so different from the present day, so that the journey to Mississippi feels like a trip back in time. Bobby Bukowski’s cinematography bathes the South in golden light, inviting us to look at it like sentimental tourists do. To the untutored eye, the underlying horror is all too easy to miss.

Mamie tries, of course, to warn her boy, her Bo, as he is known here, a pet name acquired in early childhood – but he’s a teenager getting a lecture from his mum on being careful, and we all know how that kind of thing goes down. She, meanwhile, is full of lurching presentiments, struggling to stifle her terror, yet telling herself that she’s overreacting and that it’s foolish to imagine such things when the odds are that he’ll be fine. He’s going to stay with his cousins, after all, and they know the rules. Danielle Deadwyler is remarkable in these scenes. Every parent will relate to Mamie’s reasoning, and yet the fact that we know what’s going to happen allows us to share that terror with her.

Playing Bo himself would be a huge challenge for any actor, with so much riding on it. Jalyn Hall brings an impressive lightness and ease to the role, immediately making him into someone we can understand, good-humoured and full of energy and so remote from the gravity of the material that it feels – in a good way – as if he has stumbled into the wrong film. Natural in the Chicago setting, he feels like an alien in the South, a myriad small details of his voice and bearing at odds with the other Black people around him.

Director Chinonye Chukwu is to be commended for casting someone with such obvious confidence and physical presence, as opposed to presenting Bo as a younger, more helpless-seeming child. When Bo makes the fatal mistake of flirting with grocery store clerk Carolyn Bryant (the always impressive Haley Bennett), he comes across as a teenager expressing genuine desire, rather than just a child fooling around. The film thus makes it clear that we ought to be horrified not simply because of Bo’s youth or vulnerability, but because the response to his actions was horrific in and of itself.

There is no apologism in Bennett’s Carolyn. Her own hatefulness is immediately apparent, allowing no room for the later claim that she just went along with what the men in her life wanted. The physical resemblance is striking, and importantly, Carolyn, as the town beauty, is not too beautiful – just the kind of girl whom a good looking kid might have imagined he had a chance with, and who happened to resemble his movie star crush. She’s also not too prominent, diminishing her victim narrative. After the scene in the shop, which has been painstakingly recreated and looks uncannily like the real one, we see her mostly by way of sidelong glances, never framed too directly, never admitted into the space where we might think of her as a person whose grievances were remotely proportionate to those of Bo and his family.

What follows focuses quite a bit on interactions within that family, and particularly Mamie’s struggle, after Bo’s death, to understand why others didn’t fight tooth and nail from him as she would have done. There is an important emphasis here on lynching as terrorism, its instigators as people who had disproportionate power because every Black person in the South knew that they or their loved ones could be next. The familial interactions also make clear that most people could not simply escape the legacy of chattel slavery by moving up north, because their relatives were effectively held hostage even under the Jim Crow system which followed Abolition.

The latter part of the film is interesting because, although it slows down a little too much in places, it takes a different route from most politically-related biopics. The focus is on Mamie’s slow shift from a bereaved mother who can think of nothing but her child to a campaigner determined to ensure that this never happens to anyone else. There are none of the big set piece speeches traditionally associated with winning awards. Instead we are presented with something which feels much more raw and natural. The big decision that she would make – the one which shocked the nation and succeeded in changing the way many white people thought about lynchings, tipping the balance politically – carries with it a wave of pain which makes clear that it was more than a stunt, that it was necessary but extremely difficult.

In the end, this film feels like an extension of Mamie’s choice, of her desire for the world to see and recognise the full horror of what happened in that Mississippi town in 1955. Carefully chosen costumes, furnishings, music, all speak to the period yet remind us that this wasn’t really all that long ago. The cotton fields look much the same today. At the time of writing, Carolyn Bryant is still alive. Chukwu’s film is not simply a tribute to a brave woman and a boy who died too soon. It is a challenge. Look, and understand.

Reviewed on: 03 Jan 2023