Eye For Film >> Movies >> Touched With Fire (2016) Film Review

Touched With Fire

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Carla (Katie Holmes) has been having another episode, waking her mother up in the middle of the night just for a chat, demanding answers to difficult questions, getting worried about what might have been written about her in her medical records. Marco (Luke Kirby) has been found by the police perched on a rooftop, gazing at the moon and longing for his people to come and take him away from a planet where he doesn't fit. Carla knows she has mental health problems, though she doesn't think they're beyond her ability to manage. Marco doesn't accept that there is anything delusional about his ideas. But when they meet whilst institutionalised, something clicks. It's the beginning of a relationship that will challenge them both.

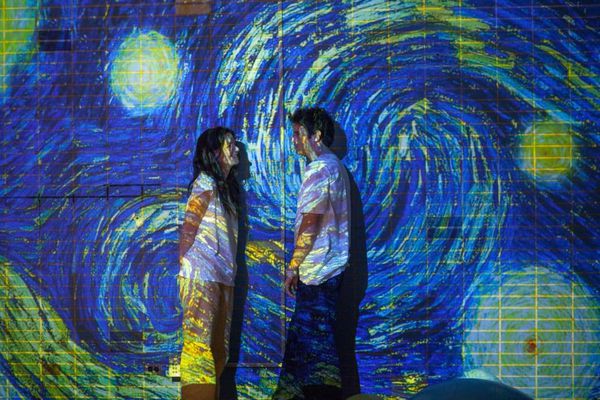

Paul Dalio is not the first director to take on the subject of romance between people with severe mental health problems, but he's one of few who have done so with the benefit of personal experience. Considering this, the balance he manages to strike is all the more impressive, and the film is constructed with remarkable confidence given that it's his first feature as a director. Particularly important is the sense of normalcy he creates around the spaces his characters inhabit, reminding viewers that, no matter how wild their ideas may seem, they are living as many thousands of people do, day by day, in similar environments. Whether it's seen as a gift or a curse, mental illness is just part of life. And yet despite this, there is a luminosity to his imagery, a beautiful use of colour, that encourages us to engage with these people and feel their joy as much as their pain.

The difficulties Holmes faced after marrying Tom Cruise, whom she has suggested tried to make her give up acting, took a serious toll on her career, so it's really good to see her back and getting her teeth into a meaty role like that of Carla. She's substantially better than she ever was when playing high profile but underwritten love interest roles, presenting us with a bruised but highly relatable woman who just happens to be emotionally unstable. Like Marco, Carla has manic depression, but they're very different people. His flights of fancy intrigue her, sometimes carry her along, but she doesn't share his conviction that their illness is a gift, providing them with enhanced creative powers. Whilst he seeks escape, she is constantly engaged in a struggle for control of her life.

Dalio doesn't demonise the psychiatric doctors and nurses trying to intervene in Carla and Marco's lives, but he does successfully communicate the frustrations of having one's freedom curtailed in adulthood, and of knowing there's a danger of forcible separation from loved ones. There's a cluster of great supporting performances from the actors playing their worried parents, patient and enduring as only lifelong carers learn how to be, yet sometimes deeply hurt by what they have to deal with. Balancing their vital yet depressing focus on things like employment, housing and adequate food and sleep is the wild romance of Marco's ideas about running away to live in the wild where the forces of nature will be on their side. It's easy to be drawn to this despite its obvious foolhardiness, and cinema is the perfect medium for it because it keeps us rooting for a Hollywood ending where dreams will come true. Meanwhile it grows more and more painfully apparent that, like addicts, our protagonists will never be able to sort themselves out whilst they remain together, will never really be able to help each other whilst clinging to their love.

The final credits of this film commence with a list of famous artists, writers, musicians and other creatives who were manic depressive. It's a nice touch - a reminder that having a diagnosis like this doesn't mean having nothing to offer to the world - but one can't help but note that a high proportion of them died young.

Reviewed on: 08 Oct 2016