Eye For Film >> Movies >> What You Gonna Do When The World's On Fire? (2018) Film Review

What You Gonna Do When The World's On Fire?

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

Roberto Minervini's latest documentary - which plunges into the African-American community of New Orleans in 2017 - is a purely observational consideration of multiple generations, complete with the intimacy and inevitable drawbacks that approach brings. Within its hefty two hours are hard kernels of truth concerning the lifelong anxieties of a community raised - with plenty of good reason - to be fearful of a predominantly white police force and its failure to protect. Themes include displacement due to gentrification, the toxic effects of white privilege and attempts to organise under the banner of the New Black Panther Party For Self Defense.

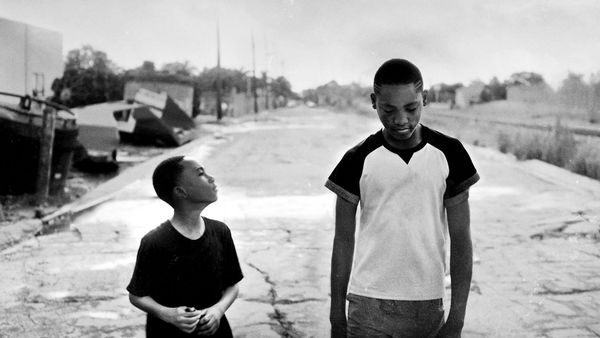

But while content is important, it is context that is king in a documentary, and this film could do with a lot more of it to orient viewers, especially those who don't have a full working knowledge of the American South. While anyone can relate to the mum and kids in one of the main strands here - Ashlei King and her sons 14-year-old Ronaldo and Titus, nine - it's harder to be drawn to the connection with the Black Panthers that are captured in the film's weakest element. Their group's anger is clear and many will recall the case of Alton Sterling, shot dead at close range in Baton Rouge by police who never had charges brought against them, but we're left struggling to glean information about the other young men mentioned here, Philip Carroll and Jeremy Jackson, who were killed in horrific racially motivated attacks. Minervini dips in and out of the Black Panther protests and grassroots activism in a frustrating fashion, so that it feels as though we never get to see fully past that anger to the arguments beneath.

Equally under explored is the presence of the Mardi Gras Indians, used here to provide a sort of musical and rhythmic chorus and captured beautifully in their downy feathered outfits by cinematographer Diego Romero. Those privy to the press notes can learn that during the period of slavery, "runaway slaves from the transatlantic slave trade were taken in by indigenous Native American people, shielded from harm and accepted into their communities". This led, down generations, to a "new masking culture" that "developed into the Mardi Gras Indian tradition" which is "an act of militancy". Sadly, because Minervini declines to have any of the meticulous artists at work here speak directly to the camera, none of this, beyond perhaps the emotion of rebellion from the end result, is made obvious by the film, which feels like a missed opportunity.

More successful is the film's final story, concerning Judy, a 50-year-old who, after a life that has included its fair share of hardships and a recovery from drug abuse, is trying to keep a bar afloat, while also looking after her elderly mum. She gives the best insight into the way that fear can become endemic in a community, describing how she was so petrified of what might happen to her after school that she wasn't able to concentrate on lessons when she was there. The film builds a successful connection between this and the emotions of Ronaldo and Titus, the older brother protective, the younger one often nervous but both all too acutely aware of why their mum wants them in the house "before the street lights come on".

The urgent subject matter here has been covered more comprehensively in films including 17 Blocks and Quest (although these films are set firmly in the northern part of the States, many of the same issues apply) and, closer to home, in Hale County This Morning, This Evening, and while Minervini's film offers moments of insight, it leaves the viewer with so many gaps to fill on their own that even those with the best of intentions may not know where or how to start.

Reviewed on: 14 Aug 2019If you like this, try:

17 BlocksBallast

Beasts Of The Southern Wild

Hale County This Morning, This Evening

Quest