Eye For Film >> Movies >> Wild At Heart (1990) Film Review

Wild At Heart is not a good film for people who are trying to stop smoking. Seldom has a pack of Marlboro red looked so achingly cool; but then cool, as with much of David Lynch's oeuvre, saturates every frame like the smoke from those ever-present cigarettes.

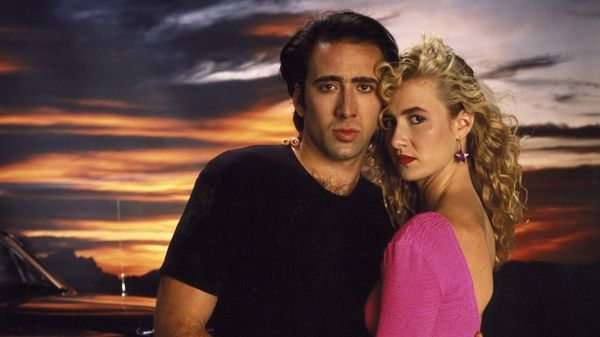

Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) and Lula Pace Fortune (Laura Dern) are a just a couple of crazy kids in love. Unfortunately for them Lula's mama, the gin-soaked, vindictive Freudian nightmare of a Southern belle, Marietta (Dern's actual mother Diane Ladd, in a genius piece of casting), is having none of it.

After trying to, alternately, fuck Sailor and have him killed, which works out well when he beats the assassin's brains out, Marietta is determined to keep her little girl away from the newly minted jailbird. The couple, awash with graphic sex and protestations of love, set out for sunny California in a convertible. They stop off to sample the magic of New Orleans and then find themselves marooned in Big Tuna, Texas.

Meanwhile, Marietta sets her competing lovers Johnny Farragut (an always-reliable Harry Dean Stanton) and Santos (J E Freeman), a shady character who has something to do with her husband's mysterious death, on their tail. Santos promises to dispose of Sailor but demands Johnny as his price. Johnny's death is one of the film's weirder detours; a crippled killer (Grace Zabriskie) kidnaps and tortures him, then shoots him in the head as the climax to an oversexed voodoo ritual with her big scary lover.

Holed up in their motel room in Big Tuna, Sailor and Lula grapple with her newly discovered pregnancy. Sailor hooks up with the fabulously toothed Bobby Peru (Willem Dafoe), a sinister drifter who's been hired to kill him. Peru talks him into a bank robbery that's planned as a hit. Will our hero survive Marietta's machinations? Will Lula keep the baby? Will love conquer?

Despite its many dark and twisted elements, Wild At Heart is essentially a love story. Plot-wise it's the most linear of Lynch's films, with only a few elements that will leave you with a sense of what-the-hell-was-that-about. The young Cage is astounding as Sailor, channelling Elvis into a performance that's all heavy romance, dark brooding intensity and perfectly delivered catch-phrases. Dafoe and Ladd, too, are impressive in their stunningly contrived evilness. Dern's Lula leaves a little something to be desired; she descends too easily into whininess, not quite matching up to her lover's iconic coolness (unlike, say, True Romance's Clarence and Alabama).

Sterling turns from Isabella Rossellini (Lynch's partner at the time), Stanton and a grievously underused Crispin Glover complete some excellent work from a very solid ensemble cast. This is a director who knows how to get the absolute best out of his stars, giving them free reign to create characters more rounded and easier to care about than is often seen in Hollywood.

As with most of Lynch's films, this is about more than the actors. His trademarks are all here - nightclubs, voodoo, whores, random incidences of utter weirdness, a fixation with the open road, rock'n'roll and American iconography - The Wizard Of Oz, Elvis, New Orleans. The brief appearances of Twin Peaks pin-ups Sheryl Lee and Sherilyn Fenn will have devotees salivating.

The meandering pace can get tedious at times, but cinematically it's a masterpiece. Every frame is carefully composed, evocatively packed with saturated colours and long slow shots. Lynch's script is also a standout; as usual, he's eminently quotable (though how much of this is down to Lynch and how much to novelist Barry Gifford it's hard to say). The tone is marked by a desire to really tell the story, but also by a light, comic touch. While Sailor and Lula's love affair is taken very seriously, they are not. The film is never heavy handed and allows the viewer to laugh at the couple. A modern Romeo and Juliet they may be, but we're not expected to forget their youth, their callowness, the faint aroma of white trash that clings to his snakeskin jacket and her too-tight trousers.

Like all great romances, this dances around the edge of cheesiness, with its intense sex scenes, serenades and meaningful looks deep into eyes. The same comic touch that keeps the characters bearable also keeps the deification of Love at a small distance. This is iconography we're dealing with here; the overblown, poetic quality of script and cinematography ensures that the viewer never feels slapped upside the head with the need to believe in romance.

This is Sailor and Lula's tale, not ours; unlike so many love stories, it doesn't leave you feeling slightly inadequate for being content with a cuddle and a curry on a Sunday night. It does, however, leave you gagging for a packet of Marlboros.

Reviewed on: 07 Dec 2005