Eye For Film >> Movies >> Youth (Spring) (2023) Film Review

Youth (Spring)

Reviewed by: Dalesia Cozorici

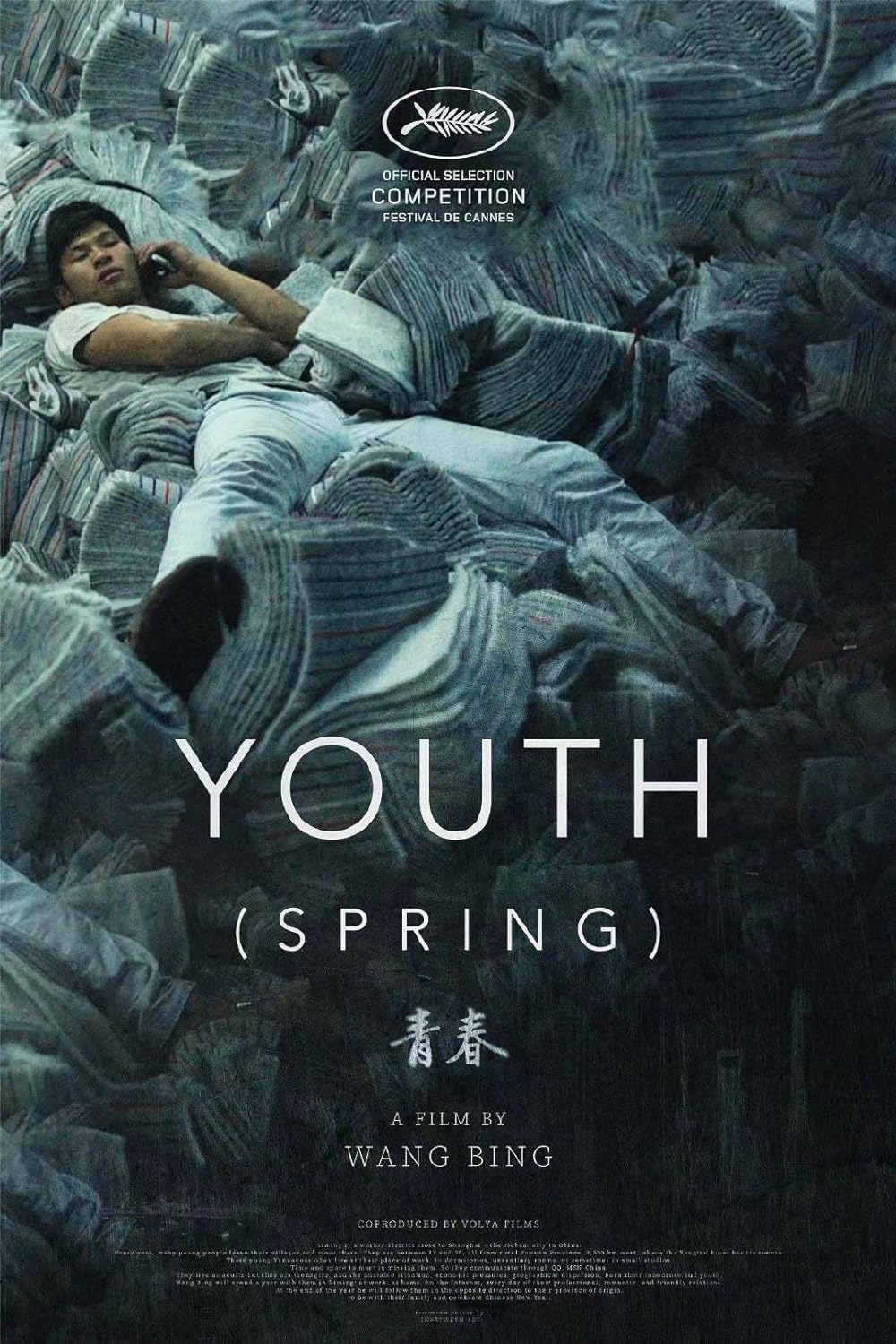

Chinese director Wang Bing returned this summer to the Cannes International Film Festival, where, in 2018, his nearly 500-minute documentary Dead Souls premiered. Youth (Spring) (2023) compromises half of those minutes, in which Wang partially abandons the conventions of observational documentary and his tendency to blend into the landscape, emerging more present than ever. However, he remains true to the idea that the created intimacy – the reciprocal bonds among the members of a small community of workers in Zhili and that which develops between them and their audience – can only be achieved through the extended moments on screen.

Workers in the tailoring workshops come from the neighboring regions of the industrialised textile city, and they are largely young, some even underage. Those who accept the working conditions are housed in the proximity of the workspaces, although the communal quarters are poorly maintained. Despite the popularity gained by the northern zone – partly due to the promotion of the complex designed for the products manufactured there (something that Wang doesn't particularly showcase) – what unfolds behind reveals individuals striving to secure the livelihoods of their families and business managers facing difficulties in maintaining stability.

However, to highlight salary negotiations and the workers' efforts to manage power abuses, Wang captures personal moments to emphasise compensation discussions. Intimate confessions or even friendly quarrels often occur, bringing moments of hope as young individuals search for romantic partners amid the mentally and physically-charged chaos. Between these two lenses, the extended montage sequentially unveils a key aspect of the documentary: the clothes made from synthetic materials, the most commonly used today, are unsuitable for manual labour. Footage captured over six years delves into an industry grappling with the challenges of overproduction, where workers struggle to break free to find something better.

Regardless of where you look, the scenario is the same; the only solace is found in Cantopop music, and even that is merely employed to cover up the harsh workplace conditions. To provide an immersive experience, sound is strategically used as a marker between long work hours and breaks. The persistent noise of sewing machines lingers, and when abruptly interrupted, it affects auditory perception. Amid this auditory dance, resilience echoes in the hum of industry.

On the visual front, the camera moves harmoniously with the workers' unpredictable gestures. Chaos ensues – for instance, when someone opens the door and rushes down the stairs, and the cameraman tries to follow, resulting in exposed frames, washed in the sudden influx of light – but there's also order simultaneously. The cinematographer pivots the camera following the protagonists in the frame, waiting as they depart and return, attempting to clarify their trajectories in constant motion. Wang has preserved instances where more people notice the camera, protagonists make remarks about the filming and interact with the cameraman, or with Wang.

But to fully grasp the situation at these workplaces, one must consider the last half a century of Chinese history, which was marked by upheavals brought about by the Cultural Revolution and the subsequent adoption of economic reforms. Diverse socialist ideas have continually shaped the politically and socially sensitive terrain, moving it toward the objective of restructuring China into a market-driven economy. Nonetheless, these reforms exacerbated already-existing gaps across social strata, labor categories, and levels of exploitation.

Wang's documentaries encapsulate an accumulation of tensions from this historical backdrop. Yet, there's also another tension. Understanding how the selection of the 2,600 hours of footage was made proves challenging; what was omitted and how did it contribute to our perception of the personnel and managers in those places? The extent to which the line was drawn regarding the workers' privacy and why Wang occasionally chose to step out of impartiality, directly participating in actions, even influencing them, can only be appreciated relatively.

Such decisions prove beneficial for the documentary as they showcase his openness to capturing spaces and people without the constraints of time or predetermined structures of a plan. Youth (Spring) inaugurates Wang's recently announced trilogy. The forthcoming instalment is anticipated to explore the challenges confronted by workers during the pandemic, persisting in the incorporation of standard documentary techniques, imbued with the fresh and humanistic vision of Wang and his collaborators regarding modern-day China.

Reviewed on: 13 Dec 2023