Eye For Film >> Movies >> Youth Without Youth (2007) Film Review

Youth Without Youth

Reviewed by: Jeff Robson

It's been 10 years since Coppola directed a movie – and he seems to want to make up for the absence by cramming at least five different films into one.

Youth Without Youth couldn’t be more different from 1997’s accomplished but fairly conventional John Grisham adaptation The Rainmaker. It’s a modern version of the Frankenstein myth as well as a deeply serious analysis of the nature of language and experience. It’s also a spy thriller, an epic romance, a road movie and a Kafkaesque portrait of isolation.

Confused? You will be, but it’s worth the effort. While this doesn’t hit the sublime heights of The Godfather or Apocalypse Now, it’s a reminder that Coppola is one of the few genuine auteurs working in American cinema at the moment. Put another way, you simply don’t get films like this from anyone else.

Bizarrely enough, the Coppola film this most resembles (in its initial premise, at least) is Jack, his pre-Rainmaker effort, which turned a standard Robin Williams vehicle into something altogether more subtle and affecting. But where that was the story of a boy turning into a man too quickly, Tim Roth here faces exactly the opposite problem.

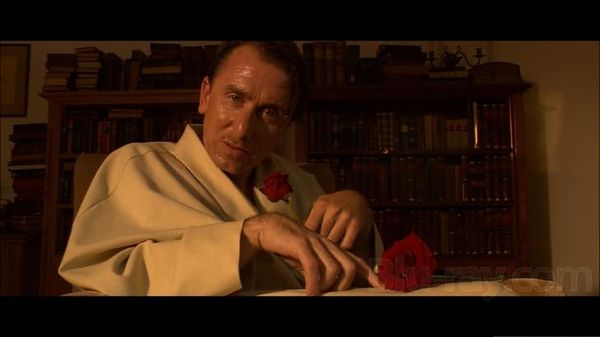

He plays Dominic Matei, an elderly Romanian linguistics professor frustrated by what he perceives as his lack of academic success and still in love with the girl who broke off their engagement 50 years ago and who has since died in childbirth. He travels to Bucharest intending to kill himself there but instead is struck by lightning outside the railway station.

Not only does he survive but he finds himself rapidly growing younger, and his brain power increases exponentially. But this is the era of World War Two, and pro-Nazi elements in the Romanian government inform the Germans of this unique specimen.

A Nazi spy (Alexandra Priciki) seduces him – easily done since he now has the libido of a 30-year-old and she happens to be the spitting image of his lost love. But a sympathetic doctor (Bruno Ganz) helps him to escape.

He spends the war years in hiding in Switzerland, pursued by Nazi eugenicists keen to recreate his lightning experience by hooking him up to the National Grid. The academic establishment, unaware of his past experiences, eagerly use his prodigious knowledge, and he supplements his income at the roulette table, finding that as well as being able to read a book in seconds, he can predict the wheel’s results. He is determined to use his new-found knowledge for good, attempting to trace the origins of language back to its starting point, and using his own invented tongue to record his discoveries on nuclear power – thus keeping them safe until the rest of the world catches up. Oh, and did I mention that an evil double has appeared, urging him to use his talents for money and fame?

After the war, it gets really weird. While hiking in the Swiss Alps, he meets a girl on a motoring holiday (the image of his lost love again – do keep up at the back!). Soon after she is involved in a motoring accident that wipes out her memory – but leaves her believing she is the disciple of an ancient Indian philosopher and speaking centuries-old Sanskrit. Dominic takes her under his wing and they fall in love. But she continues to have dream visions in which she talks in ever more ancient languages, and after each one she ages. Dominic is torn between pushing her to the point where she records the birth of language (urged to do so by his doppelganger) even though it will kill her, and saving her by giving her up...

On paper, this undoubtedly looks a bit silly, and there are frequent lapses into bathos (Dominic can also force a Nazi spy to turn his gun on himself by will power alone, handily enough) and cliché (the scenes with the Nazi seductress might as well have Liza Minelli singing tunes from Cabaret in the background). There are also times when Coppola seems to have used the film as an excuse for a gap year’s worth of travelling; now they’re in India! Now it’s Malta! At its worst, the film resembles one of those globetrotting made-for-TV Sidney Sheldon adaptations of the 80s, where everyone’s beautiful and no-one lives in less than a palace.

But adapting Mircea Eliade’s short story has clearly been a labour of love for him, and what emerges, despite the magic realist trappings, is a classic Coppola tale; Like Kurtz and Michael Corleone, Dominic is a man alone, haunted by his memories and driven to tragedy by the essence of his character. The difference here is that he is a man of thoughts, not action, but his efforts to find the answers to the essential questions are as doomed and as moving as those of Coppola’s other classic protagonists. Alas, the background narrative here is nowhere near as gripping as in his finest work. You’ll be unsurprised to hear that the end to Dominic’s tale is puzzling, inconclusive and (for me) anticlimactic.

There’s also plenty of the other Coppola on display here – the tendency to labour a point that ruined his 1992 take on Dracula, and a more than occasional lapse into pretentiousness – but with a genius you take the rough with the smooth. In an industry content to pump out formulaic dross, his desire to get an audience thinking as well as giving them ‘a thrill every five minutes’ has been much missed, and it’s great to have him back.

Reviewed on: 04 Dec 2007