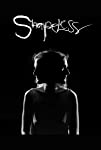

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Shapeless (2021) Film Review

Shapeless

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Ivy (played by co-writer Kelly Murtagh) is a singer with a soft but powerful voice and a distinctive style. She’s serious about what she does, and working hard to advance her career, but being a successful singer comes with certain other expectations, not least in her own mind. She not only has to sound good; she has to look a certain way, and she always has to maintain control. Her intense focus on this means that it’s getting harder and harder to do. Somewhere along the way, she has become bulimic, and now it’s beginning to overwhelm her.

People – not least those in the early stages of struggling with them themselves – tend to think of eating disorders in terms of behaviours around food, weight loss and a bit of delicate fainting. The reality is much uglier, as this film makes clear. As a body goes into starvation mode, all sorts of things begin to break down. A shortage of micronutrients interferes with the functioning of the brain, making it harder and harder to make good decisions or control one’s mood. A weakened diaphragm interferes with breath control. Bulimia, or simply an insufficient amount of food to absorb stomach acid, resulting in gastric reflux, damages the throat. Needless to say, none of this is good for a singer. It also means that the more severely one is affected by such an illness, the harder it gets to regain control.

The result of several years’ close collaborative work between director Samantha Aldana, screenwriter Bryce Parsons-Tweston, and Murtagh, herself a singer (amongst other things) with a history of bulimia, Shapeless eschews many of the demands of traditional narrative in order to explore an experience which doesn’t follow logical rules. Visually, it’s impressionistic, reflecting the psychological impacts of the disorder. We experience it almost exclusively from Ivy’s point of view, so that it’s actually the moments when we pull back from that – in the presence of professional colleagues or medical personnel – which feel the strangest. Elsewhere, as the film progresses, Aldana employs the language of the body horror subgenre to address how alienated Ivy feels from herself, and her sense that there’s another creature living inside her, trying to destroy her.

The slightness of the narrative structure here is a problem, especially towards the end, but its success in engaging viewers is likely to depend a good deal on personal taste and experience. Those who struggle with eating disorders themselves will find it easy to relate to but in places, very hard to watch. It has the potential to be cathartic viewing, as Murtagh has said it is for her, but people at risk of relapse should be cautious about watching it without support in place. The filmmakers hoped that it would help those who loved ones are in that situation to better understand how it feels from this inside, and in this regard it is pleasingly different from most of what’s out there, moving beyond the simple pathologisation of specific behaviours to provoke and inspire actual empathy.

In terms of its success as art or entertainment, it will leave many viewers frustrated (always a difficult thing to avoid when addressing a subject which is frustrating to those directly engaged with it), but it deserves credit for innovation – if not in style, then in applied technique. No doubt unintentionally, it fits within a wave of new films, most of them wiuth female directors, which are structured around experience or sensation rather than linear storytelling, and as such it contributes to an interesting process whose results are as yet unknown – but just as cinema is beginning to allow for more experimentation of this sort, so is our culture more widely, and with this in mind, what may seem a minor film today (outwith its impact on one specific community) may very well emerge as an important piece of work in years to come.

Reviewed on: 11 Feb 2022