Eye For Film >> Movies >> Bastardy (2009) Film Review

Bastardy

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

Aboriginal actor Jack Charles may not be a household name but that doesn't stop his story from being quite remarkable. One of the 'stolen generations' of indigenous kids taken from their parents and slapped into children's homes 'for their own good', he was a founder of the first ever aboriginal theatre group, Nindethana, and later The Black Theatre Group. Best known to audiences outside of Australia for his role in The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith, he has acted in many other films and TV series and in hundreds of plays.

What this brief introduction doesn't tell you is that he has also being serving time at Her Majesty's pleasure off and on for decades due to his talent for acting being matched by a skill for burglary and a formidable drug habit. Amiel Courtin-Wilson's film is an eye-opening documentary that not only tells Charles' story but also hints at the plight of many men of similar backgrounds who have also fallen through the cracks of Australian society or, perhaps, who been pushed down those cracks in the first place.

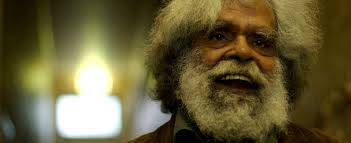

At first sight, it's hard to imagine this diminutive fella with his shock of white hair and bushy beard could be such a force of personality. But the contrast between initial scenes in which Courtin-Wilson shoots from a distance to give you a sense of this man's 'smallness' in the world and his close-up camerawork later as Charles tells his story, is surprisingly powerful. Right from the start there are no punches pulled. Charles lays out his drug paraphernalia, saying: "If I were to hide any of this I don't think this would be a true depiction of my lifestyle." It's the first, but not the last time he is captured on camera shooting up, and there's no indication of a high. "There's no outward signs," Charles says, matter of factly, "because I've been at it since 73."

Courtin-Wilson kept his camera focused on Charles for seven years, a period of time during which the actor-cum-philosopher-cum-down-and-out will show signs of taking his life in a different direction away from "collecting his debt" - a term he uses to describe robbing the affluent whites - towards a better place. The intimacy Courtin-Wilson shares with Charles is complete, as he becomes not just documentarian but a quasi-social worker, looking out for this incredible little man and even going so far as to try to spare him another trip to the nick, at the same time as charting his life and thoughts from his past.

Those coming purely to this film hoping to learn something of the actor's background, will not be disappointed, he goes into detail about being "split from our mob", the plight of his brother and about the love of his life, Jack Huston. Despite his dire circumstances he is, although sometimes regretful, for the most part upbeat - a state of affairs that somehow makes this film all the more heart-rending.

Courtin-Wilson's approach is graceful, impressionistic and with the heart of a poet. He uses Super-8 and 16mm among other formats to evoke emotions to accompany the facts as Charles lays them out, there's a sense of the old mingling with the ancient and the modern, one man's history impacting on his present. He also makes sure to document not just Charles himself, but others in his orbit, many also from the stolen generations, lost in their own sea of disenfranchisement.

Artful in a way that serves the subject matter, this is a poignant and heartfelt exploration of a life led paradoxically within the mainstream and on the fringes. Dedicated to "the lost and found", it is well worth hunting down.

Reviewed on: 21 Mar 2010