Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Machinist (2004) Film Review

Sleep deprivation, even if it's just for one night, can alter your perception of the world entirely. Vibrant colours become drained and to gain any kind of clarity, the use of industrial strength paint thinner is required. This grey, out-of-focus feeling is reflected perfectly in The Machinist.

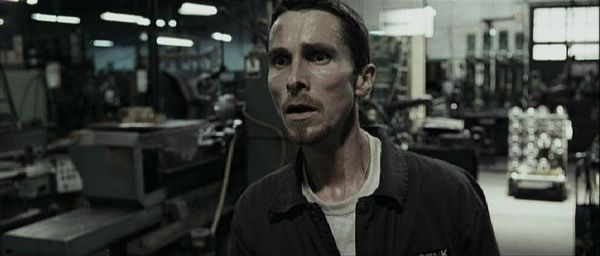

The pace drags, raising anxiety through Hitchcockian cross dissolves and harsh strokes on the violin and cello. Overflowing with symbolism and ironic dialogue, the film is beautifully washed in grey light. Despite this lack of colour and a numbing storyline, it is never anything but captivating, the graphic presentation of Trevor Reznik (Christian Bale) contrasting the slow realisation the audience feels as the plot comes into focus.

The Machinist has received mixed reviews, critics commending Bale's excruciating devotion to his craft while suggesting the film follows a much travelled path, revisiting the psychological unwiring seen in Fight Club and Memento. Yet, it offers up originality in the form of the protagonist, a bony insomniac who works as a machinist and lives in a decrepit apartment, alone, turning to call girls for companionship.

Director Brad Anderson (Session 9) shows no compassion when presenting Reznik's weight problem, causing the audience to resist sympathising with him. Although we take part in Reznik's confusion over what is happening to him, Anderson keeps us at a distance, allowing us to witness Reznik's increasingly dangerous paranoia without involving us in it. So, when the film reaches its climax, our mixed feelings slip into distaste, similar to Leonard Shelby's character arc in Memento, except more unflinching in its resistance to empathy.

At first, it seems like we won't be receiving any explanation as to why Reznik is anorexic and unable to sleep, but this becomes more apparent as the film goes on. The Machinist is dense with symbolism, which at times may seem too overt, such as Reznik's fairground ride on Route 666. However, the ridiculousness of the set-up is clearly intentional.

Reznik looks on in disbelief at what is happening around him - mangled corpses from car wrecks on a children's ghost train - and the audience is told that something is bubbling to the surface, while also being given an insight into his mind. We must never forget that most of what we see is a figment of Reznik's guilt-ridden subconscious, which Anderson communicates expertly through his use of on-screen metaphor and strong use of symbolism, as well as ironic self references.

The style enhances the psychological nature of the plot. Hitchcock was always one to delve into the twisted minds of his characters and Anderson heightens the quality of the story by borrowing some of his tricks. The chase sequence, where Reznik looks for a Red Firebird, is reminiscent of Psycho, the short sharp high notes in the soundtrack raising tension while communicating the prickling unrest in his mind. These scenes, which utilise cross fades and overlaps to cement the idea of a dream-like haze, contrast with the stark cuts in less tense scenes, where the editing is sharp, almost mechanical.

The Machinist will, in time, become more highly appreciated. Bale's performance is superb, his devotion to the role scary - the producers are said to have refused to let him drop an extra 20 pounds - and yet there is far more depth to this film than superficial shock value. Anderson has used cinematography, editing, sound, script and symbolism to its fullest potential, reflecting expertly the inner workings of a psychotic mind.

In places it feels overlong and at times is difficult to follow, but The Machinist remains a high quality film, combining graphic disbelief with thought provoking substance and a hint of dark humour.

Reviewed on: 28 Mar 2005