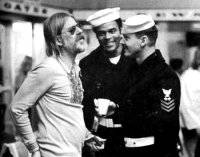

Ashby directs Jack Nicholson on the set of The Last Detail

With a straggly greying beard, white flowing hair, a cigarette eternally connected to his whiskery lips and ripe-for-the-times rose tinted glasses, Hal Ashby was tired. Long days and long nights at the Moviola had left him a virtual insomniac yet, with an precise eye for the right snip, the hazy days of the 'sixties saw Ashby begrudgingly become the most sought after editor in Hollywood. He wanted out.

Born to a Morman family in Ogden, Utah, Ashby was a rebel on the road to Hollywood. A high school flunkie who found himself married - and subsequently divorced - by the age of seventeen, it was a simple epiphany that carried him away from a languid existence. In search of the fruits ripe in California's sun-dripped land, he upped, left, and began his journey. Sadly, this journey was to begin and end in the turbulent 'seventies. In a decade where combustible talent came to town, decadence and downfall were only a knock away - Hal Ashby was soon to become the ultimate Hollywood casualty.

Starting out with jobs as an assistant to William Wyler on The Big Country and George Stevens on The Greatest Story Ever Told, Ashby used the swinging 'sixties as his time to fine-tune an emerging talent as an editor. It took a triumphant first cut of Tony Richardson's The Loved One before studio heads began to turn and a creative partnership with master helmsmen Norman Jewison beckoned, propelling Ashby into a dizzying stratosphere. This talent payoff culminated in an exhausted rebut at the Academy podium.

Perhaps it was the time Ashby invested in putting a film together that prompted him to create controversy by telling the press, upon receiving an Oscar for In the Heat of the Night, that he would use his accolade as a doorstop. He was working seven days a week, seventeen hours a day! Ashby felt he had learnt all he had to; he was ready to become a director and, at almost the age of forty (ten years senior to the talents-in-waiting of Spielberg, Milius, De Palma and so forth), with full Academy recognition, he found that filmmaking was his true calling.

Through his close relationship with Jewison, Ashby was soon handed his first shot wielding the megaphone. Adapted from its novel form, The Landlord was an intriguing comedy that, tying in with Ashby's own active political stance, contained a solid message. Relative to Rod Steiger's winning turn in In the Heat of the Night, the unknown Lee Grant bagged a Supporting Actress nomination. From this, all the way up to Jon Voight's Oscar nabbing turn in Coming Home, there was a clear indication that Ashby's time sweating it out in the editing suite had forged an uncanny ability to jigsaw together dramatic scenes, a trait that consistently proved a winner in awards season. He was, most definitely, the actors' director, his ability to coax out a performance summed up by Jack Nicholson who declared him to be one of the greatest "nondirectors" of all time.

Anticipation surrounding Ashby's sophomoric feature was high. With Harold And Maude Ashby and producer Charles Mulvehill were certain their black comedy, indie appeal would grant an audience in the mainstream. Sadly, the tale of Bud Cort's death-obsessed youngster falling for Ruth Gordon's life-loving granny turned out to be an unprecedented flop. With elements of social satire and a quiet anti-war message, Harold and Maude was a feature too far from the norm. Lambasted by critics and ignored by confused audiences, the film was described by Variety as 'about as funny as a burning orphanage'. A flurry of scathing reviews proved to be a death sentence for a film that bore all the qualities of a true new wave classic, released before the new wave truly began. However, Ashby's "failure" has fared well with time. Achieving cult status through the video boom and even the writings of Douglas Coupland, Harold and Maude later found itself at No.45 in the AFI's list of 100 Funniest Movies. But later success was irrelevant to the director's career at the time. Ashby's rising star was stalled. He was now in need of a hit.

With studios jittery about handing the unproven Ashby another budget, his next feature, The Last Detail, was a low cost tale that was slow to gain a definite green light. With a lack of interest in Robert Towne's script - an adaptation of Darryl Ponicsan's novel - Ashby turned down helming the tale of navel lifers "Bad Ass" Buddusky and "Mule" Mulhall as they escort a young sailor cross-country for a stretch in the brig; but after a second read he came to feel differently. With numerous changes from the novel (increased amounts of obscenity, a daringly pessimistic climax) Ashby jumped on board and Columbia reluctantly agreed to distribute. Securing Jack Nicholson and Otis Young in the roles of the disillusioned naval men and unknown Randy Quaid as the doomed Larry Meadows turned the project around; it was Nicholson's star on the rise that helped The Last Detail avoid being culled by disapproving studio heads. Lobbying for the copious use of profanity and - importantly - the implementation of Towne's revised ending, the freshly Oscar nominated actor paved the way for The Last Detail to begin production.

Despite it bearing the hallmarks of a producer enfant terrible - Mulvehill frequently clashed with Ashby, even vowing never to work with him again -Ashby turned The Last Detail in, on time and within budget - a regimented success. But would its risqué content chart under audiences' radar?

From its sweary poster premise The Last Detail was a success. Well, of sorts. With Columbia unhappy about the disjointed cuts Ashby had applied and still more so with the quantity of profanity, it took a triumphant screening at Cannes to get a release date. Ashby's rage-within-the-machine ethos, Towne's blitzkrieg scripting and solid performances from the three leads all anchored its kitsch in the new wave realm. A classic in the making? No doubt. But with poor box office returns Ashby had struck out for a third. As The Last Detail sank Ashby was gearing up for Warren Beatty vehicle Shampoo - in its wake he never looked back, as his short directorial career neared its end.

If time and tide wait for no man, then Ashby's fish[head] out of water tale was the perfect encapsulation of his skills. Where drugs, alcoholism and a spiralling ego left him awash in the eighties, The Last Detail stands tall in his, and the decade's, body of work. It has an impassive yet soul-affirming view of institutionalisation. For machismo I am the motherfucking shore patrol, motherfucker! I am the motherfucking shore patrol! Give this man a beer!" is a testosterone spouted thwack upside the head. But beneath Towne's dialogue the beating heart of Ashby's Detail is worn on a uniformed sleeve. Stuck on "this chicken shit detail" Buddusky and Mulhall enjoy their brief stint of freedom. They show Meadows, their prisoner, the sights. He tastes the sting of a bar room brawl. He experiences the bittersweet lows of falling short in the company of a hooker. Through this R-rated rite of passage the three bond. With Nicholson playing the livewire master of ceremonies to Young's quietly learned take on life both leads are exemplary.

From the cracked greys of train station platforms to the blustery neon soaked side streets of a Boston we were never meant to see, Ashby's strengths behind the camera draw equal attention. Under the autumnal to wintery shine of Michael Chapman's cinematography, with touching character nuances spliced to perfection - earning another Oscar nomination for newcomer Quaid and the unstoppable Nicholson - The Last Detail's emotional core comes wrapped in a stoic socio-political message. Buddusky and Mulhall are lifers. Nuff said. Meadows may be facing a long stretch in solitude, but the three are all akin under the oppressive umbrella of the regimented military. With the transition to winter, where Detail's grubby vistas are blanketed in white, the cold climax sets in and, with its downbeat climax, one of Buddusky's quick fire zingers comes home to roost: "Why does all of this make me feel so fucking bad?" Expletive, but on the mark.

Though Academy recognition of Ashby's directing skills arrived at the decade's end for post-war drama Coming Home, it is still The Last Detail which stands as his crowning moment. Quietly directed and superbly realised in its underlying themes, this is anti-authoritarian cinema projected from a sacred source - the anti-authoritarian mind. Never bettered and never beaten, this is Ashby's indelible mark on cinema, like his untraceable - yet riveting - direction. Hal Ashby is a master begging to be exhumed and rediscovered.