It's not talked about much but a lot of critics have a fear of the middle seats in cinema rows from where, if they hate a movie, they have to clamber out over 15 or so disgruntled people who love it in order to escape. As someone who has only walked out of two films in my life - and regretted it both times - I like to think of myself as 'fearless' in that regard. Which would be great, if only I could remember my schedule early in the morning.

So, it came to pass that as I sat in the middle of a row in the Kursaal cinema - with around 20 full seats to either side - to watch Iran Hostage Crisis film Argo, the credits rolled and I realised it was Blancanieves (about which, more in a later update), which I had watched a mere 12 hours before. Admittedly, extracting myself from the cinema wasn't quite in the same league as trying to extract a group of petrified Americans from a country before they are killed but if looks could do the same job as guns, I wouldn't be writing this now. And trust me, getting into a Mexican stand-off staring match with a woman who refuses to budge is not a great way to start the day.

Argo - when I finally got there two minutes in - soon made me forget all of that, though. Ben Affleck's latest is a gripping thriller which, incredible though it may seen, is based on real events. Back in 1979, when a group of Islamic revolutionaries stormed the US Embassy in Tehran, 52 Americans were held hostage, it became world news. What didn't make the TV, though, was the story of six Embassy staff who escaped before the lock-down came and found themselves holed up at the Canadian Ambassador's house.

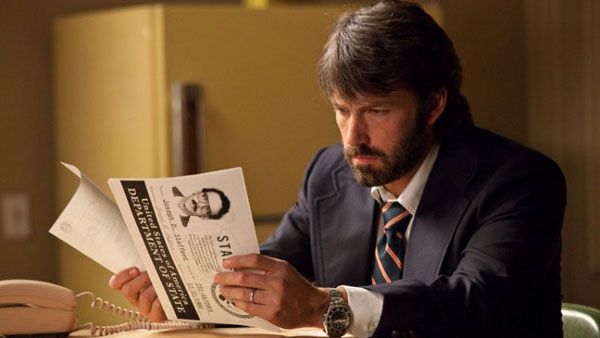

Affleck plays Tony Mendez, the "exfiltration" specialist, who is taxed with getting the six out of the country before it's too late. He hatches "the best bad idea they have" - pretending to make a science-fiction movie named Argo as a pre-text for getting into the country for a 'location scout', and then giving the six Americans movie cover stories to sneak them out in plain sight.

Affleck, perhaps surprisingly, finds plenty of humour in the situation - particularly from the double act of John Goodman and Alan Arkin, who play their roles of Hollywood make-up artist and producer essentially for laughs. But when it comes to turning the screw in terms of tension, the director - who puts in a measured and engagingly understated performance as Mendez - delivers a nerve-wracking last quarter that notches up the nervousness to almost unbearable levels.

There's high tension, too, in another snapshot of history recorded in Clandestine Childhood (Infancia Clandestina), which is based, at least partially, on director Benjamin Avila's on experiences as a youngster. It tells the story of Juan, a 12-year-old who, after living in exile with his family, returns to Argentina, in 1979, with a new name - Ernesto - and parents who are determined to maintain the 'Operation Counterstrike' to topple the military dictatorship.

Avila - whose own mother was one of the 'disappeared' - presents the film from Juan's viewpoint, so that we see the same snatches of militant conversation between his parents and their comrades as he does but are also immersed in his own move towards adulthood, including the flutterings of first love. It's an interesting move that keeps the story rooted in Juan's perceptions, giving a sense of the lasting effects left on children who were forced bystanders of their parents' struggle. The director makes great use of animation at key points in the film - mainly concerned with violence - as though they are the storyboard imaginings of what Juan believes happened more than documents of fact.

The subject of military might also raises its head in Pablo Larrain's No. The film, set in the dying moments of Pinochet's rule, records the run-up to the 1988 referendum on his presidency that the dictator was forced to hold. Using a camera from the period - which gives the film a 'muddy' TV look - Larrain is able to seamlessly blend his own film with large amounts of archival footage from the time to paint a picture of a vote that was less about actual politics and ideology than about selling a dream of the future.

Advertising executive René Saavedra (Gael Garcia Bernal) finds himself co-opted onto the 'No' campaign to reject Pinochet even as his boss Luis Guzmán (Larrain regular, Alfredo Castro) is being called upon as an adviser for the 'Yes' camp. The result becomes as much a personal battle between the two men as between the parties their films are set to represent. Larrain shows how both men treat politics like a product to be sold through advertising that has more similarity to a Coke advert than a party political broadcast. Black comedy lurks in almost every scene and while there is knowing humour to be had from looking back at what modern viewers might consider to be some of the campaign's 'dafter' moments - mime artists, anyone? But there is also a very serious point being made about politics in general that spreads way beyond the reaches of Chile and the Eighties, to ask us to consider just how we are all susceptible to manipulation through advertising.

Rounding out the festival's first few days of blasts from the past was Olivier Assayas's Something In The Air (Apres Mai), which presents a snapshot of the Seventies from a French perspective. Loosely based on his own experiences and that of his friends, the director paints a picture of French youth in revolt against the police in the years following the 1968 student uprising in Paris. Gilles (Clément Métayer) is just one of many young Frenchmen and women, blending creative, hippy-style tendencies, with a destructive impulse. Assayas's depiction of a summer of love (and quite a bit of hate) has an intimacy that brings the politics down to a personal level. While it does have a tendency to meander in places - mirroring in many ways that the youngsters are meandering their way towards adult convictions - it scores on an emotional level and is likely to find favour with young rebels everywhere.

More soon on films including the black and white joy of Blancanieves and the elderly love of Michael Haneke's Amour. If, that is, there are no more schedule slip-ups.