|

| Jakob (Michel Diercks) tries to unleash the beast. |

It’s a small production originally made as a graduation film, but it has drawn praise from critics around the world and festival audiences love it. Now The Samurai is set for DVD release in the UK. The story of a shy policeman in a small German town and the mysterious cross-dressing stranger who tries to bring him out of his shell by wreaking havoc with a sword – and who just might be connected to the wolf he has secretly been feeding – it’s a film that is greater than the sum of its parts, a film that challenges and entertains without sacrificing its central ambiguity. It was a pleasure to talk to its young director, Till Kleinert, and ask where it all began.

|

| Pit Bukowski as the Samurai |

“I’d been a student for a very long time,” he told me. “It became clear that at some point I was going to have to make some sort of graduation film. When I was looking for something to make I got the initial idea and then lots of stuff started coming together. I used to draw comics when I was a teenager – that was my in, into visual storytelling – so when I make a film there’s always one or several strong images there at the start. In that case I was on a train to Berlin that was going through lots of forests and I look down, out of the window, at all the little hamlets. It was dusk and there was no-one on the streets at all. There as a strange sense of foreboding, as if all the little houses were huddling together against some kind of threat. An image popped into my mind of a lone figure walking through the streets rattling a samurai sword along the fences. From then it was about figuring out who that guy is and why he’s there. I didn’t start with the policeman; I started with the antagonist.

“I never thought to make the Samurai the protagonist,” he continued, “maybe because I’m me! Even though I’m attracted to violence in fiction I would consider myself much more of a square person, more repressed, so I look for avatars for myself. I don’t know if I’m really thinking about how general audiences would relate to it. In many ways I think Jakob (the policeman) is much more disturbed than the Samurai. The villagers sense something in him that he’s not quite aware of. All the stuff the Samurai does is something he harbours. In a sense the Samurai is doing his dirty work for him, releasing all that pent up anger and all that frustration. The Samurai is pretty sure of himself, pretty straightforward. It feels like it’s Jakob’s agenda to stop this guy.

|

| Back to nature. |

“The relatability of Jakob has been questioned at some Q&A’s as many people take offence at how bad a policeman he is, because he’s very soft, he has a very unclear sense of agency. People would rather have character who’s mucho macho and much more aware the of things he’s doing. Jakob’s motivations maybe needed to be made more clear to make it more palatable but for some reason I like this uncertainty.”

I told him that one of the things that struck me about the film was how it resembled a fairytale. He said that this emerged in part because of the wolf.

“That was another thing I added to the first image. Wolves are coming back in the area. They have been extinct in Germany for more than 100 years but now they’re slowly returning and several people are very afraid of that. They’re not very rational feelings connected to the fact that people are afraid for livestock and children, but others have a strange romantic longing for that unkempt wilderness, perhaps because of the perception of the wolf in Grimm fairytales. I have grown up with Grimm tales. My mother read them to me when I was a child and they made a lot of impact. So that’s part of my toolbox.”

A lot of the images he uses, he went on to explain, are not conscious – they’re simply ideas that have formed in his mind over the years because of the things he’s read or watched. This came up again when I asked him about the strong element of queer sexuality in the film, something that intrigued me because it often gets in the way of films winning over mixed audiences, but that doesn’t seem to have happened in this case.

|

| A policeman's lot is not a happy one. |

“In a way since there’s cross dressing, which has always been a part of it ever since the character first cropped up, and because of me having been a repressed young gay man, it became quite autobiographical in some ways... but I think it took a while until the producers, who are also very close friends of mine, told me this is what the film is actually about. I have been very coy only talking about what happens on the surface level.” So far, Till’s career has involved a lot of work with the same team off people. I asked him if this was advantageous in helping him bring his vision to the screen without compromise.

“Yes. definitely,” he said. “It goes the other way round as well. Anna [de Paoli] produced with Linus [de Paoli] directing as well. I was an assistant on his short films and I acted in his feature films. We work very closely together when it comes to developing scripts. It’s good to know where you stand with feedback, especially if someone’s telling you you’re not there yet. People you trust might know better than you where you might be going. It was easy have that sort of collaboration in film school but right now I’m initiating a new thing, developing a script, and I’m not clear whether I feel as good about working as a production company.”

Part of the business of production is, inevitably, the battle to find finance. The Samurai was originally designed to suit a possible grant of €250k but ended up having to be made for €150k. This meant that a lot of people ended up working for free, something that still makes Till feel bad. He hopes that one day he’ll have a project with a proper budget and be in a position to pay them properly.

|

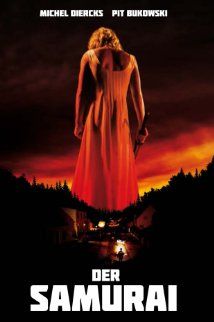

| The Samurai poster |

His new project is a television series. “In the GDR [former East Germany] they built those model socialist towns. They were not so much about high rises themselves. The whole idea about the layout of these little model towns was ideologically charged, the idea of a new kind of living for new kind of people. I had the pleasure of growing up in one of those towns. A lot of things frightened me about living there. There was a very uncanny feeling and for a long time I have wanted to make a series about one of those tower blocks. After Reunification the fell out of fashion. Nobody wanted to live there anymore and they got old pretty fast because of the impossibility of adapting them to more individual needs. Now the only people there are people who’ve hit rock bottom. I want to tell a story about one of those buildings, its inhabitants and about something else living there with them, something that crept in from the foundations and is squatting in the empty space where the ideology has gone. It’s about the quest of the people who live there to figure out what’s wrong and to figure out how to get rid of the thing.”

How about other films? He must have been excited by the response The Samurai got at festivals, I suggested.

“I’m very grateful,” he said, sounding it. “I didn’t expect it to do much. I would never have imagined it travelling so well. I’m grateful for every reaction, even negative ones, because I always learn a lot about film from talking to people. I don’t know yet if it has opened any doors but I hope it will help me to make other work.”