|

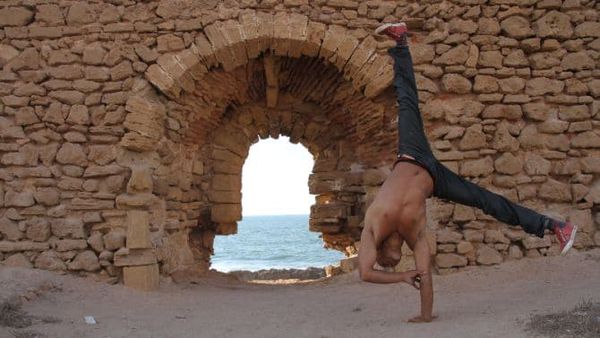

| Imed is the ancient pirate fort. |

A grim city where the jobs and hope have gone. A wild coastline where pirates once roamed. A hidden pavilion where young people, once bereft of dreams, are training to do things they never imagined – to be circus performers. Pirates Of Salé is a documentary about these young people and the adults who train them. It’s a story that director Merieme Addou stumbled upon accidentally in the course of her work with BBC Morocco, and which she couldn’t resist following up on.

“We heard about a new youth project teaching children circus skills so I went to do a report about it,” she says. A native of Salé herself, she was intrigued by what she saw, and when she met fellow documentary maker Rosa Rogers a couple of years later they began to talk about returning to find out more.

|

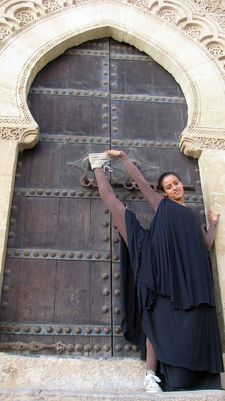

| Ghizlane practices her stretches. |

“In Morocco we don’t have the tradition of circus so for me when I first saw a circus it was like things that I never expected to see here,” she explains. “Especially in a city like Salé. There are not many opportunities for children. No work, no theatre, no cinema, nothing.”

One of the boys in the film, I note, says that when he first saw a circus he assumed all the acrobatics were faked.

“Like an illusion, yes,” says Rosa. “Salé looks a bit like a war zone in some places. We came through this area where Ridley Scott filmed Black Hawk Down, and there are ruined buildings everywhere. There’s nothing for miles and then you come through it and see the sea in the distance and the circus tent rising out of the old fort like a mirage. Inside it’s like a dream world, a magical place, and we tried to capture that in the film. It’s like stepping into a different world.”

People now travel to join the Salé circus school from all over Morocco, because success there can open up huge opportunities for them, enabling them to travel abroad and discover the world. Only a few make the cut, however, showing the right combination of physical skill, creativity and appetite for hard work.

“It is arduous,” says Merieme. “It’s not easy and simple, but then it’s never easy to find an opportunity to become an artist.”

There is a tradition of street acrobatics in Morocco, Rosa says, but it’s not seen as artistic or even particularly creative. It’s more like busking. “This is seen as something completely different,” she adds. “It’s a world apart from street acrobatics. People are really blown away by it. They may have seen an international circus on television or in a film but they’re delighted to see something like this coming from Morocco.”

Getting involved with the circus is a particularly big step for the young women, who would not normally have many opportunities to make their own way in life. Most girls are expected to finish their basic education and then stay at home until somebody asks to marry them. Unfortunately, the Pirates circus is in a dangerous area, more run down than other parts of the city, which causes problems for girls who want to train late.

“Generally girls don’t walk around much on their own at night but it is dangerous in derelict areas,” says Rosa, stressing that there’s a real reason for them to be concerned. One of the girls in the film, Ghizlane, was mugged travelling home from her training sessions. I ask after her, concerned that she might have been forced to give it up, but Merieme has good news.

“She managed to find work with another circus and she’s been working with a circus in Turkey. Now she has come back to Morocco and she’s making a small performance society.”

|

| Pirates Of Salé |

“She was in Turkey for about a year,” adds Rosa.

“Yes. Because she doesn’t have the papers she cannot stay longer. Now she’s working in Morocco again but she might go back.”

“It’s the same old story,” says Rosa. “If you’re from a country outside Europe, the US or Australia, it’s hard to get a work visa, which makes things difficult because most of the big performance groups are in Europe, Canada or the US.

The contrast between these challenges, the difficulties of daily life and the remarkable beauty of the circus performances were what made the subject compelling for Rosa, nd “more poignant than it could have been if we were filming a group of young people in France or London.”

“It’s the circus, not school really, where they learn their skills,” says Merieme. “It’s about more than the performance. It’s about life, the way they see life and think about things.”

“They’re learning to challenge the world around them and think critically and creatively,” adds Rosa. “It’s a real journey for the because most of them have never done anything like this before. They’re engaging with the world politically.”

I ask if that might put them in a risky situation in a country where politics can be volatile, but Rosa says she doesn’t think there’s anything in the film that gives her cause for concern, and points out that part of the point of what they are doing is finding their voices, learning to say what they want to say publicly.

“There is an example of that when Imed is performing,” notes Merieme, referring to one of the young men in the film. “He has a speech he makes and everybody is hearing what he is saying.”

“Imed in particular,” Rosa agrees. “His piece is quite political, he’s wanting to provoke; as a group and individually they use performance politically to confront people’s ideas and get people to think about things.”

Merieme is now going on to work on a piece about women who have been left behind by their husbands and are seeking divorce; it’s complicated, she says, and she’s still at the stage of finding the right subjects. Rosa, meanwhile, is focused on promoting this film and her last film, Casablanca Calling, about upcoming female leaders in Morocco. She then plans to travel to Indonesia to make a documentary about the way that children with special needs are being integrated into its school system for the first time.

Both are really excited about Pirates Of Salé screening at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

“In some ways this film is about a specific situation but we made it because we felt it had something really universal and could encourge children to follow their dreams,” says Rosa.

“For me what is important is it shows that when you give children - or in the end, people - an opportunity, you really see the fruit of what you are looking for,” says Merieme. “They just need opportunities and in Morocco there have not been many.”