|

| Estranged |

Recently released on the new Frightfest Presents label, Estranged is the story of January (Amy Manson), a young woman who is seriously injured in a traffic accident and returns to her family home to recuperate – with no memory of her life before the accident happened. It’s a tense, claustrophobic drama that gradually takes on a more sinister aspect as, despite growing physically stronger, January comes to feel increasingly powerless and threatened. Adam Levins, the director, is better known as a cinematographer, and one of the first things one notices about Estranged is its striking beauty – it’s a very visual film. I asked him how much this owed to his past work.

“I can’t really take the credit for the cinematography because Gary [Shaw] is a really good cinematographer and he’s older than us too – he’s worked on stuff like Moon and Fortitude – I mean, he was this big commercial guy but he moved more into high end TV drama, so that’s a big part of it,” Adam says. There’s a self-deprecating tone in his voice that belies the quality of the film.“ Obviously I lean more towards the visual side of things as a director,” he adds. “I don’t come from a writing background so I tend to put more emphasis on telling the story through images. I’m just not the world’s best writer, basically!

|

| An eye for danger |

“What I’m working on now is getting more into the writing side. I don’t tend to write a lot of dialogue but Simon [Fantauzzo], the screenwriter, is a good friend of mine and he has an incredible way of working with dialogue. When I came to this I did edit down some of dialogue though because it’s not really my thing. Obviously it’s still a very dialogue driven film and that’s important to the story but I guess I tried to steer more towards visual aesthetics. I just kind of focused on the house and the isolation because it’s about her [January] being so isolated and it’s about the isolated location.”

The house in question is a country mansion surrounded by acres of woodland. It’s very much a character in the film, thanks partly to Adam’s emphasis on the visual, and as January struggles to recall her past, her relationship with the house becomes a key aspect of the story.

“The house is definitely like her little prison though it’s actually quite large so on one side there was the isolation and on the other there was a sense of all that space,” Adam says. “Isolation is hard to do these days because we’re all so much more connected, so it was like this other world where there aren’t really mobile phones and things. We didn’t want it to be like a period piece but it’s like stepping into a different time. We were able to make it feel like she’s just in a slightly different world where these kind of crazy things could happen and she can’t just go and pick up a phone and get help.

“With her being stuck in a wheelchair, she’s in a massive house but if she’s at the top of the stairs she can’t come down so she’s basically trapped. Then there are more obvious things like the basement, which is obviously a really claustrophobic place, where they lock her up for a while.”

|

| January in her wheelchair |

I explain that I’m a wheelchair user and that I felt the film did a very good job of picking up on little details that make that experience feel real, from the comments other people make about it to the unexpected physical limitations January encounters. Adam is surprised and pleased, and tells me he hadn’t really been sure how accurate that aspect of the story would seem.

“I feel like I maybe should have gone further to be more realistic about it. I was uncertain about the speed at which she’s recovering from her injuries so we created a later sequence where we go through the seasons and have her learning to walk with the mother. I don’t think we did a lot of research into that part of it really. Obviously we researched how quickly you can recover from an accident and the stages involved. I think we talked to one or two people who had worked in rehab who were just friends of mine.”

Although her disability emphasises January’s disadvantages, she’s not the only character facing challenges. Adam and I talk about the way the characters developed and the stylised, slightly surreal way that some of them come across onscreen.

“I think Lawrence especially is an out there character,” Adam says. “He’s one of the characters who went in his own direction a bit. For the most part we stuck to the script and what’s on screen is what’s on the page, but James Lance did a lot of research on his own and created a whole back story with all this crazy stuff. I was like, go with it. It made the character quite tragic in a way, even though he’s definitely a psychopath, he’s quite disturbed. It was just like crazy, with all these women he’d killed and hidden bodies around the manor.”

Little of this background comes through directly in the film, though it all makes sense with the character Lance portrays. Likewise Nora-Jane Noone, as sister Kathrine, hints at a much more complex story than we ever see – it gives the film a sense of mystery and depth that goes beyond the main plot and helps the viewer relate to the heroine’s amnesiac sense of disorientation. Acknowledging that most abusiveness goes on between people who are closest to each other, Adam is also intrigued by these siblings’ relationship to one another.

|

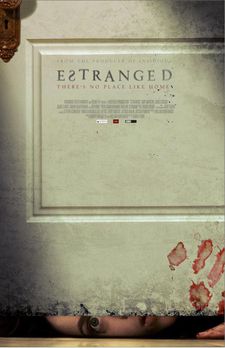

| Estranged poster |

“I think that really Lawrence and Kathrine are more harsh to each other under the surface than they are with January, Lawrence especially because everything he’s trying to do is about wanting to be upper class and January is a class above him so I think he looks up to her, although England is less and less this way. It’s constant going on, little bits of nitpicking. I think in his own way Lawrence is constantly trying to befriend January so when she says Get in the room! he’s like, Me too? and it’s like I thought we were friends.”

With all these different things going on in the film, I ask him what the most appealing part of it was for him.

“I think I always was working towards the end really,” he says. “There’s a great sense of frustration that she can’t do anything in the beginning, then when she’s trying to do something she gets stopped. So the revenge scene I guess.”

He also has another film out this year which, he says, is a documentary.

“Population Zero is sort of a look at this particular case where there’s this loophole in the American constitution where there’s this one little area in Yellowstone National Park where you can get away with murder,” he explains. He means it literally. The film follows the case of Dwayne Nelson who, he says, approached park rangers in 2009 to confess to the killing of three young men in the park, and who was subsequently released when they found that no-one had the power to hold him.

“I’m back now to working on a more drama type thing,” Adam adds. It’s a science fiction, futuristic dystopian thing. I’ve actually been wanting to do a more low budget science fiction thing for a while. But with Population Zero it was just a different way of filmmaking because in that situation you can be a bit more off the cuff. A lot of that time it was just me and Julian [T Pinder] up in Canada hanging about in Yellowstone and going around, me with a camera filming him as he was speaking. It’s actually very liberating when you’re used to having 30 or 40 people around you on a set. It’s really good just to get out there with like one person, and tell a story.”