|

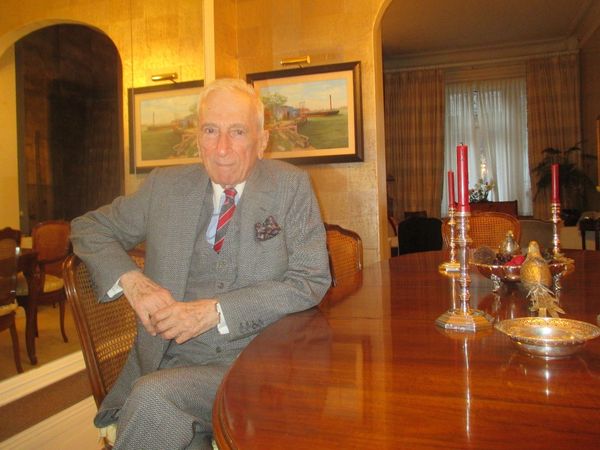

| High Notes and The Voyeur's Motel author Gay Talese seated at the dining room table where James Baldwin came to dinner with his brother David. Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

When I told author and journalist Gay Talese that I was working on a feature for Raoul Peck's Oscar-nominated film I Am Not Your Negro, he agreed to meet with me at his home this week to share his personal memories of James Baldwin and to discuss the film that he had just seen: "The documentary I saw at Lincoln Center on Baldwin was an exceptionally relevant and historically important portrait of one of the most important writers of my lifetime. As a prose stylist, few Americans used the language more eloquently than Baldwin did."

Anne-Katrin Titze: You knew James Baldwin well. What did you think of I Am Not Your Negro?

|

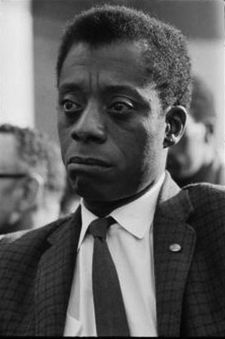

| Gay Talese on James Baldwin: "In the documentary he was thinking, pausing. In his writing, of course, there's no pauses." |

Gay Talese: The film was so important because I am 85 years old and I don't know whether James Baldwin was younger or not. I just suspect he was close to my age. I was born in 1932. If you have any idea what year Baldwin was born it would help me.

AKT: 1924, I believe.

GT: As I think about my generation of writers - in one generation, a good part of a generation's literary giants can just be diminished. It doesn't take more than one generation for the writers that inspired me or that I otherwise admired - my children's generation can have a whole new cast of characters in a literary sense. And a generation later of grandchildren has a different sense of the world entirely in terms of what the written word did in his lifetime.

He wrote with such a graceful style, of the most traditional of English stylists - Henry Jamesian sentences. Long convoluted, literary but also in his sense representative of the black anguish. He was a ferocious writer in that his writing was angry but eloquent. Angry can be loud, crude, singularly rude, meaningless in a way. When I started to read him first in fiction and then in nonfiction, the nonfiction that I read was mostly in magazines. Really mainly in Esquire in the early 1960s because at that time I happened to be writing for Esquire a lot myself.

|

| James Baldwin: "He was a ferocious writer in that his writing was angry but eloquent." |

And going into the office frequently, I at times would either hear the editor talking on the phone to Baldwin - the editor being Harold Hayes - or on some occasions I actually met Baldwin and cultivated an association with him that led to a friendship. The friendship started in 1961 or '62 and at that time I was a reporter on The New York Times but writing in my free time for primarily Esquire magazine. I would invite Baldwin and sometimes his brother David to have dinner here. At the table you can see, that dining room table. This house then looked as it does now - hardly any changes for half a century.

What was so interesting about him as a person, not as a writer but as a person, that he wasn't angry. To tell you the truth, people like me then in the Sixties and now in 2017 don't really know a lot of black people. I don't care how we profess to reach out and being accepting and egalitarian, we don't know many black people. And unfortunately the black people we do know are celebrities, public figures. Baldwin seemed to be very comfortable with white people. Only I say that because it contrasted very much with his scope as a writer and his intention as a writer. His writerly world was at the wrongdoing of the white man.

AKT: His arguments are so precise and cutting too.

GT: Oh yeah. Cutting but it wasn't the truncated sentences, it wasn't staccato. It was like an opera. You had the orchestra going up and down the register. It was really musical, the writing, in a way. He spoke in something of the same way. You saw that in the documentary. In the documentary he was thinking, pausing. In his writing, of course, there's no pauses. It's all compressed and choreographed. It's very beautifully moving from paragraph to paragraph.

My personal relationship with him was without contentiousness - ever. However, I do recall one evening in this very house. It was somewhere in 1963 or '64 that Baldwin came to dinner with his brother David and four other people. Three of them from The New York Times. And one of them - a very well-known columnist named Tom Wicker. Tom Wicker who was from North Carolina was once the Bureau Chief of the Washington Bureau of The New York Times.

|

| I Am Not Your Negro director Raoul Peck Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

Wicker was the guy that wrote about the death of John Kennedy. He was in Dallas on the occasion when Kennedy was assassinated. He wrote a wonderful front-page story that's reprinted many times. Wicker was outraged about the racism of America and wrote it many times in essays and columns. Wicker and his wife Neva, both of them are Southerners. Like many people in New York who are Southerners, they did everything they could to show how un-racist they were.

At The New York Times there was an editor who was from Mississippi, named Turner Catledge. The Turner in that name was after a man who was the head of the Klan. Turner Catlledge's grandfather fought in the confederate army and was related to William Bedford Forrest. You know the movie that Winston Groom wrote that became a Tom Hanks movie? That stupid guy from Alabama?

AKT: Forrest Gump.

GT: That guy! Forrest Gump - the name comes of William Bedford Forrest who was this Klansman. Related indirectly to The New York Times managing editor. But here was a Southerner from Mississippi who was in Club 21… Let's get back to Tom Wicker.

|

| Gay Talese: "My personal relationship with him was without contentiousness - ever. However, I do recall one evening in this very house." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: Back to the dinner table right there.

GT: I can show you exactly where they were sitting. I remember that Baldwin was going on and on having just returned from Selma. This was before the march. A year before the march. The march was in '65 so this must have been '64. And he had something to say about the South. Tom Wicker, even though he is this liberated liberal New Yorker and Washingtonian but with roots in North Carolina took exception and one thing led to another.

And whatever decorum had prevailed at that time at this particular dinner party erupted with the wife of Tom Wicker saying "Don't talk to Tom like that!" She is looking at Baldwin. But Baldwin was going on and on and not interruptible and big red-faced Tom Wicker was large, probably 6'2", not fat but very heavy. But the little wife, Neva, never saw her husband so assailed verbally having, no doubt, never met James Baldwin before. Baldwin looked at her and just stared.

And then she burst into tears and Tom said: "This is my wife. Now, she is not part of this." And Mrs. Wicker runs over there to the living room, buries herself in the curtains that you could see still this day and was weeping uncontrollable. Baldwin and his brother were completely silent. My wife Nan was there. I was there. I didn't say anything.

|

| I Am Not Your Negro poster at the Film Society of Lincoln Center Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

I just was thinking about the liberal whites from the South who came to the North and were baptised they thought into the egalitarian mission of good-thinking white people. And here was the dark angel of literature from Harlem, James Baldwin. And this exchange of comments didn't work. That's the only time I saw Baldwin in person in an argumentative mood. Although I've seen him on television and so has everybody else. And this movie [I Am Not Your Negro] I saw the other night recalls that.

AKT: There's a great quote in the film where he says: "White people are endlessly demanding to be assured that Birmingham is on Mars."

GT: That's right. I had a little example in my living room.

Coming up - Gay Talese on the importance of James Baldwin now, Baldwin's essay, Letter from a Region in my Mind in the New Yorker, the structure and use of film clips in Raoul Peck's I Am Not Your Negro, and being on another planet.

I Am Not Your Negro is a highlight of this year's Glasgow Film Festival.

Public screening at the Glasgow Film Festival: February 22 at 6:00pm - Glasgow Film Theatre.

I Am Not Your Negro is in cinemas in the US.

The Glasgow Film Festival runs through February 26.