|

| Preparing to ride restless horses |

A journey through the mountains to return a dead sheikh to the ancient city of his birth takes on a spiritual dimension in Mimosas, Oliver Laxe's strange combination of western, modern day thriller and mystical epic. It was born out of a five year creative process, says Laxe, so pinpointing where ideas came from is difficult, but nevertheless he's prepared to share his thoughts on the experience and what it taught him.

"I was was very clear that I wanted to make an affirmative film mixing adventure with religion or mysticism," he says. "It's an experimental film in a way. In this creative process I travelled to a lot of places: Mauritania, Morocco, Senegal, Iran, Turkey. I was living in the south of Morocco to explore the location where I wanted to shoot. I had the idea to make a film of a caravan crossing the mountains."

|

| Shakib and Ahmed looking for answers in a canyon |

Developing the characters of the nomads who undertake the journey was, he says, about working closely with the actors, who were his friends. I asked myself what touched me about them. I invented them like they are, like Shakib, for example, he has this innocence in real life so I tried to capture this innocence - he's like a wise fool." He pauses, checking that the expression makes sense in English; speaking in his second language, he has a rich vocabulary clearly drawn from books, and though he will check like this several more times before our interview is over, he never actually falters or seems unable to express himself.

"Said is someone who is a strong leader," he continues. "He shows his ethics and values in the way he speaks, the way he looks, the way he sits, the way he smokes. Ahmed has a mystery in him, this his silence that I like. It's a sceptical silence. That's why he's the main character, because of his scepticism."

It's a film about friendship, he says. "A very innocent friendship. They have a mission and they have to look after themselves."

He visited the area with the actors and a producer who urged him to shoot near the cities, pointing out lots of beautiful locations there, but he was determined to make things more difficult.

"One of the rules of life is that things will never be easy," he says. "The best fruit will be on the top of the tree where you have to climb to get it. It has to be earned. There have to be dangers - you have to deserve things. That's why I proposed an experience so excessive."

Did he find what he was looking for, as a result?

|

| Mountain snow |

"I wanted to make a film that made me less of an idiot, that changed me. That's why we make art, why we make cinema."

Travelling, meeting people, it's all part of the same process, he says.

"Also, when you're shooting outside, you can see your limits. It's like in the film, they have to carry the body of their master. Ahmed says he knows the path but he doesn't. This is beautiful in human nature. We think we don't know the way but we do. It's about intuition. Like Ahmed I thought I didn't know the path to follow for the film. That can give you fears, but I found I knew it. The film made itself."

There were also real physical hardships for cast and crew, shooting out in the wilds.

"Most of the routes we had to go with mules because it wasn't possible with cars. One was three hours with donkeys and we had to cross a lot of rivers. It was difficult for the crew and we were tired.

"What is good when you have obstacles in life is that it's always better than what is written on the script. I like to have a submission to the film like that. The filmmaker is just a bridge. You are trying to provoke something that transcends yourself - that's why cinema is such an amazing tool."

To complicate things further, Oliver and his production became semi-fictionalised subjects in another film, The Sky Trembles And The Earth Is Afraid And The Two Eyes Are Not Brothers, in which Ben Rivers portrayed the director floating down the river into the hands of less friendly local people who turn him into a form of living musical instrument.

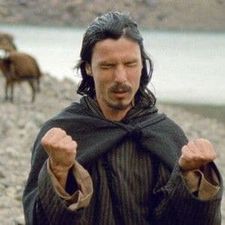

|

| Shakib tries to divine answers |

"Ben was very interested to make a film about a filmmaker," Oliver explains. "It was very exciting. He wanted to shoot my shooting with actors in location. I was afraid to be told what to do - that's why it was very good experience. I was telling myself not anything is mine, I cannot say no to an artist."

The films are very different, he notes, and he and Ben had quite different working methods too.

"For me the difficult thing was that he was making his movie without a script. I like that, but I had a strong, big script, so I was afraid that he was making a better film than me! Obviously I'm human and my ego was telling me that oh, he's gonna make a good movie and you're not. But I thought, if I'm not able to catch the beauty of these people and these places than there's Ben behind me doing that, and it's an important thing to do that. It was sweet to share this experience with him But the other thing with his film was that they had better donkeys than us. We were really jealous of their donkeys."

As well as coping with substandard donkeys, Oliver's team had to deal with technical issues and difficult weather and, at one point, take a few days out to restore a road so that they could get their equipment to where it was needed. They ended up with five weeks in which to shoot eight weeks' worth of material, and then they had to deal with the horses.

"The horses were not cinema horses," he explains. "They were not castrated. They were very wild, so it was very difficult to shoot when they were all the time moving. But I was looking for problems making this film because I like this energy.

"Editing was easier than shooting and I edited it with an editor who is a musician. That's important because this has been described as a spiritual western or a metaphysical western but for me where the spirituality or transcendence is in film is in the gaps between the images. It's in the editing, it's a spiritual journey. I'm a filmmaker who believes that something mysterious happens between the image on the screen and the human soul in the theatre.

|

| Ahmed and Said must make a decision |

"I like to explore a deep relationship with the spectator. This is a very narrative driven film and it's very clear: there are bandits who surround and persecute them, they are lost, they are thirsty and they protect themselves. But it is also a place mystery. When you're editing you don't know if you want to be more clear or more obscure. With cinema the best way to be clear is to be obscure. It's a little bit contradictory.

"We are very Cartesian and very rational but even if sometimes we are watching a movie and thinking about it and the mind is all the time making questions about it, still something deep is happening. I hope the images of the film, its geometry and the music will penetrate in the theatre, whether there are spectators who are used to that or not. I think there is a place for everybody. There are some audiences who like to understand everything, some don't like suspense. There are others who enjoy it more when there is mystery."

His preference, he says, is for obscurity.

"It's like when you open a door and have a lot of light coming in, you don't see nothing. That happens with a lot of films. Everything is very clear and you don't see nothing."

Next up for Oliver is a film about arson and a firefighter, to the filmed in Spain; then a psychedelic road movie about young European punks travelling through Morocco. "Again you have two dimensions: the epic tale and the mystical tale."

Mimosas is in UK cinemas now.