Rebecca Miller's Arthur Miller: Writer; Doug Nichol's California Typewriter; Andrew Rossi on Okwui Okpokwasili's Bronx Gothic; Elvira Lind's Bobbi Jene; Michael Almereyda's Escapes on Hampton Fancher; Brett Morgen's Jane on Jane Goodall; Ceyda Torun's KEDi; Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum's Letters From Baghdad with Tilda Swinton voicing Getrude Bell; Griffin Dunne's Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold; Agnès Varda and JR's Faces Places; Neasa Ní Chianáin and David Rane's School Life; Ferne Pearlstein's The Last Laugh; Lara Stolman's Swim Team; Kirk Simon's The Pulitzer At 100, and Josh Koury and Myles Kane's Voyeur on Gay Talese's The Voyeur's Motel are some of the highlights of the 170 documentary features submitted for Oscar consideration for the 90th Academy Awards.

Amy Berg and Roger Ross Williams hosted a screening and reception at Soho House in New York for The Work, directed by Jairus McLeary with co-director Gethin Aldous which has been nominated for a Gotham Award and has a chance to make the Oscar shortlist of 15 to be announced in December.

|

| Amy Berg co-hosted with Roger Ross Williams the Soho House event for The Work Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

When you hear "retreat", chances are you won't imagine spending four days in a Level 4 prison with convicts, many of them incarcerated for life. Yet this is precisely what Jairus McLeary and his team capture for us in The Work. Volunteers join inmates in group therapy sessions conducted in a room inside Folsom Prison and go on a Campbellian journey into their individual bellies of the whale.

Charles, Brian, and Chris - three very different men with a common thread step into an unfamiliar external situation to discover that the uncanny resides far closer to home than they might have suspected. Once the often very male games subside, a universal vulnerability emerges. The work works. The programme, as stated in the film, has had a 100% success rate. Not a single inmate who participated in the programme and was released had relapsed and returned to prison.

Anne-Katrin Titze: How long has this programme existed?

Jairus McLeary: It started really after a riot in 1997 at Folsom State Prison. And this is New Folsom, which is California State Prison which is right next door. The entire prison went on lockdown for seven months and he read Viktor Frankl while he was in the hole.

AKT: "He" is who?

JM: Patrick Nolan [seen in the film]. He was an Aryan Brother. Viktor Frankl wrote Man's Search for Meaning and he is from the Third Viennese School of Psychology [Psychotherapy]. He essentially was in the concentration camps and wrote and lived his discipline in prison - that's how he survived.

|

| Jairus McLeary on Folsom State Prison: "My dad asked me if I wanted to go ..." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

And Patrick Nolan saw the similarities and he dropped out of the gang and he essentially didn't understand psychology but he wanted some of the heads of the gangs and he recruited them to sit in a circle, just like dudes have been doing for the last hundred thousand years. Like hunters sitting around a fire. And he realised he could do that. That's how it really all started. The first 4-day was in 2000, 2001, so it's been going for 20 years.

AKT: How did you find out about this?

JM: My dad is a former clinician and he was one of the first guys that Rob, one of the founders of the Inside Circle Foundation - the guy with the beard - asked to come inside. Because he needed to get a group of men who he thought could hold themselves in prison.

And my dad asked me if I wanted to go because we had been doing this work together as a family since I was 16 years old. And he asked my brothers and I to go in. Eventually we did. I said no twice before I went in because I didn't understand prison.

AKT: Of course. When you say you did this work as a child - which part of the work do you mean?

JM: Peer-to-peer group therapy. There are programs and organisations out there, one of which is called the Mankind Project that host sort of initiatory processes that utilise therapy and Jungian psychology. I did one of those.

AKT: In your film they were all so versed in it, I noticed.

JM: They meet every week inside the prison. You don't need a degree to do this type of work. You just have to physically do it, and emotionally do it. And when you're doing that every week for a year, for two years, for three years, for ten years, you get pretty good at it.

|

| Jairus McLeary: "Charles was our local bartender. Chris was an old friend of a friend of my older and younger brother. And then Brian went to my high school." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: How rare is this for prisons - this kind of program?

JM: This is the only prison programme that's like it. This is level four prisons. It's called the Inside Circle Foundation. They operate in New Folsom, so it's California State Prison and San Quentin [State Prison]. And there are other offshoot organizations because this is a voluntary initiative. Private citizens run the program. The state does not pay for this programme.

AKT: It should.

JM: It should, but it does not. Basically, the volunteers pay for it. Just regular people from all over the world. They run it and then go back to their own communities. They hear of it by word of mouth. Essentially, if it calls to you, because you know someone who did it, you might decide to then volunteer. That's how you get new members. Those people come and then decide to maybe do something in the state or the country they go back to. In Boston I know there's a program called the Jericho Project - it's in a level three, not a maximum security, prison.

AKT: In the film you show the prisoners talk about their childhood memories, when they were five or in any case very little. This is when you could hear the greatest gasps in the audience here at Soho House.

JM: We could all do that right now. I could go in this room and we could all sit down.

AKT: Good luck.

JM: No, we have judgements who each other are and people have prejudices. If you see a guy who you think looks like … who is not like you, who may have ...

|

| Life Animated director Roger Ross Williams Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: … a neck tattoo?

JM: Tattoos, yeah. You will make up stories about that. But once you get past and underneath all of this stuff - at rock bottom we all have some of the same experiences and the same issues. Even a guy like Chris you see in the film - essentially he felt rejected by his father - versus something more violent. It's not the same, but what hurts you hurts me. And it all stems from these moments.

AKT: So from having your father be your father to this film, what made you decide to do it after having rejected even going there early on?

JM: It was one of the most potent experiences of my life, being in that room. So I would go repeatedly and it was just amazing. People would ask me and my brothers, like, what are you doing when you go there? And I tried to explain it and it's just unsatisfactory to say it in words, you really have to experience it. At some point I was working in L.A. in the independent film industry and I decided - well why can't we film it? So we could show people. And we started to talk to the guys on the inside to see if that was something they would be interested in. And they were.

At first half of them said no because there are repercussions. They cannot live the way that you saw in the film on the yard. Because everything is divided by race and gang and you can only show … the safe emotions to show on the yard are anger and violence. You can do those things but you cannot cry and you cannot show weakness.

|

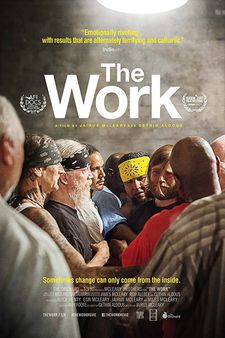

| The Work poster |

But enough of those guys said yes because they knew that there are so many negative voices about them on the outside that they wanted to have a positive voice. They wanted people to see that they are human beings and that not everybody in prison are bad people. Even if they'll never get out they're trying to maximise their life.

AKT: You are showing early on that they all agree to leave the outside world of the prison [the gang affiliations] behind. And the volunteers? How did you decide on these three men?

JM: Just like I got it - word of mouth. All those three guys were guys from our lives, my brothers and mine. Charles was our local bartender. Chris was an old friend of a friend of my older and younger brother. And then Brian went to my high school. He was a few years older than me. He was in my older brother's class.

AKT: So you knew them and said - go in there? Do this?

JM: They also had heard about this before and we talked about it and they said that seems like something I'm open to.

AKT: I have to tell you that after the screening was over I was very happy to go outside and see some women.

JM: It's very masculine. That's why Amy Foote, our editor, and Alice Henty, the producer, they were the first women to see this footage. We shot in 2009 and we finished the film 2015, 2016 and they were the first people to see it. They saw this footage and used, I guess, their ignorance of this to make it more relatable.

So in every frame of the film there is femininity there that Amy put there and that Alice put there and made it more relatable maybe to people who don't do group therapy or that might not be familiar with that type of aggressive, masculine stuff.

AKT: Talk about the rituals. There are some that are very poetic. There's chanting.

JM: Whatever works.

AKT: It seems like a patchwork of different methods. There isn't one dominant methodology.

|

| Soho House screening room in New York Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

JM: That's exactly right. There's not one discipline. This started out of a creative place. Patrick Nolan would write poetry and published poetry and someone from the outside read it - Don Morrison. Rob Allbee [an executive producer of The Work] went in to teach a creative writing course because he was also a published poet.

The origins of this are based in poetry and something called the Mythopoetic men's movement which is Robert Bly and Joseph Campbell and all those guys who were reacting to feminism and saying what can men do? Like the women we see out there marching are doing. The other part of it is, Don says, the program is shameless in their borrowing. It's whatever works.

AKT: It's powerful to see in action.

JM: Most of those men assume that they are never getting out of prison. And they want to live what is left of their lives in prison the best way they can and make it the best life that they can. And a lot of these men are actually getting out of prison because now the parol board is on to this program and they know that the rates of violence are going down. And a lot of these guys who are leaders of the gangs are dropping out of the gangs.

AKT: The film lets us come close to human reactions rarely seen on screen.

JM: We wanted the audience to be as close inside the circle as possible and we did that so Chris, Brian and Charles represent sort of a cross-section of dudes. Chris is just a young white guy who didn't really know what to do with his life. Brian is Syrian, he was a teacher's assistant, very judgmental. And Charles is African American, he is a bartender and a family man. And if an audience identifies with these guys and asks why would they be there, they're not buying into this at first. Then they slowly do. They are placeholders for an audience.