In New York for uniFrance and the Film Society of Lincoln Center's Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, Bruno Dumont joined me for a conversation at the Loews Regency on Park Avenue to discuss divine inspiration, and how he interprets Charles Péguy's nationalism, his Catholicism, and socialism. In his latest film, Dumont puts thought into action with eager young actors who sing and dance and summersault to produce a cinematic work unlike any you have ever seen.

|

| Bruno Dumont with Anne-Katrin Titze on making a musical out of Charles Péguy: "It's truly a very strange idea, yes." Photo: Nicholas Elliott |

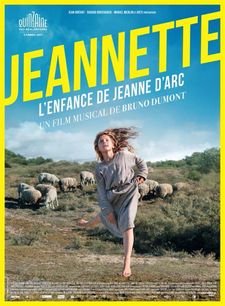

After Camille Claudel, 1915 starring Juliette Binoche, and his absurdly funny Li'l Quinquin and outrageous Slack Bay (Ma Loute), Dumont astonishes us with Jeannette, l'enfance de Jeanne d’Arc that breaks every rule. The dynamic performances, the sung dialogue (about questions of faith of all things), the fact that two people are referred to as one character in Madame Gervaise, the choice of music, and the choice of lyrics form a mix that is trance-like, brave and defiant, just like little Joan. The history of trying to understand the divine is a long and winding landscape - from passion plays to The Sound Of Music.

Jeannette, L'Enfance De Jeanne D’Arc is faithful to the text of poet/philosopher Péguy on the childhood of the young Joan of Arc and once you accept Dumont's wild setup and his unorthodox approach, the fun can begin. How do we really imagine the life of saints? What were children like in the 15th century? Eternal greatness encounters sacrifice and the film dares to musically tackle questions of complicity in evil.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Péguy! Who would make a musical out of Charles Péguy?

Bruno Dumont: It's truly a very strange idea, yes.

AKT: You have a moment where Jeannette is praying. "We need a warlord to end all wars," she says. The fact that Charles Péguy died in combat during the first months of World War I - that's what I was thinking about at that moment. Did his death have anything to do with your making of the film?

|

| Bruno Dumont: "Cinema is a place of belief and I completely believe in Saint Michel, Saint Catherine and Saint Marguerite suspended in their tree." |

BD: No, it exists. It is true that he died tragically. I think there are correspondences between Joan of Arc and Péguy. And indeed the bringing together of the vapours of poetry and war, this is quite a singular thing to bring together. And that is something that we find both in the life of Péguy and in the life of Joan of Arc.

AKT: His three big subjects were socialism, patriotism, and Catholicism.

BD: That's the right order! In the chronology of his life that's the right order. When he wrote Joan of Arc he was 20 years old. He was a complete socialist and an atheist at that time. When he wrote the second Joan of Arc 20 years later he was a complete catholic. And in the film you have both parts. The part of his youth and also, especially in the first part of the film, of the second part of his career.

AKT: And these, his three subjects, are also subjects that interest you?

BD: Yes, because I'm interested in religion. Not in its institutional form but in its poetic form. And that's why Péguy interests me. Because he's very singular, even for the Catholic church. He's a marginal.

AKT: Even in Slack Bay, the apparitions, the way people float away - that's absolutely in the same vein.

|

| Bruno Dumont on Jeanne (Jeanne Voisin): "She is in action. She does what she believes. And I agree that power is in action." |

BD: Absolutely. I'm into religion, I'm dealing with religion since La Vie De Jésus [The Life Of Jesus]. I think that title, La Vie De Jésus, bringing those two things together, that contradiction is exactly what I'm trying to do. That is to say, the embodiment, the incarnation of religion in cinema. Personally I think that religion has nothing to do with our era and that it should go back to its place. That is to say to the theater and that means - the cinema.

AKT: The scene when you have Saint Michel, Saint Catherine, Saint Marguerite appear in the tree, I was thrown back to my childhood. That's how I imagined saints.

BD: Yes, that's where they exist. And I believe that they do exist in cinema. Cinema is a place of belief and I completely believe in Saint Michel, Saint Catherine and Saint Marguerite suspended in their tree. Because that's where they belong in cinema.

AKT: Madame Gervaise is two people. I was reminded of the concept of two bodies of the king made flesh. That was very likely not the thought behind it, but of course in cinema you can have two people who are one.

BD: That's exactly the work that the viewer can do which is to let the twins enter her imagination. For me that was not at all it. When I did my casting, there were two of them and I didn't want to separate them.

|

| Jeannette (Lise Leplat Prudhomme) with Hauviette (Lucile Gauthier) |

AKT: Another link to your previous film: "We know what to do but we do not do." Joan of Arc does do. Is there a direct link?

BD: Yes, absolutely. For Péguy, thought is in action. Thought is not in thought. And I agree with that. Like Bergson, thought is in action. Joan of Arc is like that. She is in action. She does what she believes. And I agree that power is in action.

AKT: I love how Péguy states that there is nothing more honorable than work.

BD: When he made Les Cahiers De La Quinzaine, which was his literary work - that was the most important thing in his life. The salt of his life was this small business in a sense. He was someone who made something, who had a business. And it was Les Cahiers De La Quinzaine.

AKT: Tying this to the girls dancing and singing in your film - you can see the work. They are performing with all they have and that's really nice to see.

BD: Yes, and a director directs or in the French a réalisateur realises. My job is to put actors into motion. Because I believe cinema is action. Action is thought. So I make sure that the actors do not think. They're supposed to not think. I put them in motion.

|

| Face to Face with French Cinema by Jean-Baptiste Le Mercier - Bruno Dumont and JR with Agnès Varda hanging in the Furman Gallery through March 18 Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: There are two moments in particular, one at the beginning, one near the end, that share the humor of your last two previous films, which were comedies. The first moment is the timing of the sheep's meeh. Near the end you have the uncle tumbling off the horse in a moment of slapstick. Are you coming back to comedy after this film?

BD: Joan of Arc is a tragedy but I believe that in tragedy we always have comedy. I believe in the tragicomic. In comedy there's like an overflowing that goes into tragedy. And vice versa, tragedy overflows into comedy.

This is something that I discovered when we did Camille Claudel which is a tragic subject but we found ourselves on the shoot laughing. We were in a situation that was contrary to it. And I believe in this coincidence between genres. The genres are not separated. The further we go in tragedy - we see this in tragedy - the funnier it is. That's how we have the uncle who is funny.

AKT: I see what you mean.

BD: In vaudeville, for instance, we have the husband, the lover, the mistress. That's a comedy. But if the husband shows up with a knife it turns into a tragedy.

AKT: The idea of not actually having a genre is also in the sense of Péguy very much?

|

| Jeannette, L'Enfance De Jeanne D’Arc poster |

BD: I discovered the circulation of genres between each other in mysticism, not in philosophy. Because in philosophy we separate things a lot. I understood this by making films. When I would find that there was something lacking in a tragic scene, that's when I understood there was the comic coming in.

There's an element of chance in the scene. And that it's not that you're in one genre or another, tragedy or comedy, there's going to be a slight shift. Something is going to move a little bit within the genres.

When Camille Claudel is walking and slips on a banana peel that's hilarious. That's because it's Camille Claudel who is doing that. There's some kind of rupture there, a breach there that's kind of actually the very nerve of comedy. It's a question of relationship. It's a question of equilibrium, balance, and rupture. Breaks.

Coming up - Bruno Dumont on poetry and literary expression being "a very difficult tricky thing", the importance of music bringing us to the trance, the cinematography of nature, and what he has next in store for us.

The uniFrance and Film Society of Lincoln Center's 23rd edition of Rendez-Vous with French Cinema in New York runs through March 18. Screenings will take place at the Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center.