|

| Mathieu Kassovitz: 'La Haine was a very political movie which showed a Paris that had not been seen on the screen before' Photo: Unifrance |

The interest was unusual as the film was written and directed by Mathieu Kassovitz, a then largely unknown young filmmaker and actor. Moreover, it was filmed in black and white, with no big name stars on a small budget. In Kassovitz, France, it seemed, had produced a young, talented and provocative filmmaker to rival American directors like Spike Lee, Quentin Tarantino or even Britain's Danny Boyle.

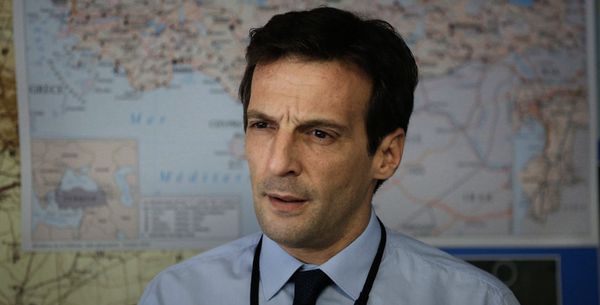

After playing the romantic lead in Amèlie, which is about as far away from La Haine as you can get, and directing the big budget spectacular The Crimson Rivers, Kassovitz, at 25, became one of France’s most sought-after talents. Recently the 53-year-old has found a new incarnation as the debonair spy archetype Guillaume Debailly, an intelligence officer who’s called back to Paris after six years undercover in Damascus, in the espionage TV series The Bureau (Le bureau des légends) now in its fifth season and an international hit.

Kassovitz fell into the business almost in the natural course of events. His mother Chantal Rémy is a film editor, and his father Peter is a director. Born on 3 August, 1967 Kassovitz spent a lot of time on his father’s film sets and at a young age he fell in love with the work of Steven Spielberg with whom he worked on Munich, in which he played a Belgian explosives expert, alongside Daniel Craig and Eric Bana. Even today, he finds he has more in common with US cinema than le cinéma français.

|

| La Haine poster |

At 17, he left school to make his way into the business. He made his first short film Fierrot le Pou at the expense of Godard’s 1965 Pierrot Le Fou. He accomplished his breakthrough as an actor in Jacques Audiard’s See How The Fall, opposite Jean-Louis Trintignant, for which he won a most-promising actor César award.

He told me once that La Haine was "a very political movie which showed a Paris that had not been seen on the screen before.” He continued: "I deal with three tough kids, a Jew, an Arab and an African. It was a success all around the world because the kids have the same problems in New York, London and Paris or wherever. And the one I did after it was very political too, Assassin(s). As a director, when you have the chance to express yourself in a media that is as important as cinema - which goes everywhere and everybody can see it - you either go for pure fun which can be good too (and I love to go to see these movies in the theatres), but for the ones I like to make I need something else. I need a soul in it, and if I do not feel the soul then I do not enjoy doing it."

I also asked him why he thought we saw so relatively few politically engaged films nowadays? "The movie industry has changed a lot in the last few years because of digital effects, I think, which inspired a lot of directors to make films that could not have been made before. It changed a lot of things. So now it is easier to make action movies with amazing stunts that you never saw before, because now they do not have to do them for real. So we are seeing less and less of serious and conscious-raising cinema and more popcorn cinema for the teenage market. On this project it was OK because we were lucky to have a producer like the late Claude Berri who financed the film. But it is true it is getting more and more difficult to make a political movie, but more because of the way the industry has changed rather than because people are scared of the controversial elements."

He had more than his share of unwelcome limelight at the time of La Haine. The film won the best director award for him at Cannes which caused a furore. “I was getting all this hostile attention. It was seen as very anti-police so I got a lot of shit from the police as well as from journalists,” he said stoically.

His first feature film as a director was Métisse (also known as Café-au-lait), a fast-paced and streetwise inter-racial comedy, also featuring his La Haine actors Vincent Cassel and Hubert Koundé. His much anticipated third feature as a director, Assassin(s), stirred almost as much controversy as La Haine, for its depiction of society’s attitude to violence and the manipulation of the media.

The stir around La Haine caused was, in part, due to its controversial subject matter - les banlieues (the suburbs) - which had, since the 1980s, become synonymous with France's major problems of unemployment, social exclusion, racial conflict, urban decay, criminality and violence. It was also due, in part, to its negative portrayal of the police who, with the exception of one officer of North African descent, are represented as violent, racist and uncomprehending. And in part to its sympathetic, some might say indulgent, representation of an excluded and multi-ethnic suburban youth.

|

| Mathieu Kassovitz was an international hit in The Bureau Photo: Unifrance |

La Haine was shot in black and white, on grainy film stock, on location in a suburban housing estate called La Cité de la Nöe in Chanteloup-les-Vignes (Yvleines). It signalled an affinity with la Nouvelle Vague of the Fifties and Sixties, rather than the extravagant production values of the Eighties and Ninetiess. The initial story came from a real-life shooting of a 16-year-old Zairean youth called Makomé Bowole in police custody in 1993. Makomé's death went relatively unreported and unnoticed.

One of the trends that generated considerable media attention at the time was the emergence of the so-called cinéma de banlieue. Films like La Haine (1995), Thomas Gilou's Raï (1995), Jean-François Richet's Inner City (1995) and Karim Dridi's Bye Bye (1996) confirmed a new preoccupation with the gritty reality of France's run-down suburbs.

The trend has echoes today in such films as Ladj Ly’s first feature Les Misérables (so called after Victor Hugo’s classic novel set in the suburb of Montfermeil). The film has had an incredible career from its bow at the Cannes Film Festival last year when it won the jury award, an Oscar nomination for best foreign film then no less than four César awards as best film, best newcomer (Alexis Manenti), best editing (Flora Volpelière) and the audience prize. It was also named European Discovery in the European Awards, was nominated for a Golden Globe as well as an Independent Spirit Award and won best film, best director and best screenplay in France’s Lumière Awards. Comparisons were quickly made with La Haine - even after 25 years - illustrating that perhaps not that much has changed in the intervening period.

After the hostile reaction to Assassin(s), Kassovitz felt the need to escape the hothouse atmosphere of France and spent time in the States. “I had to get away because of the big problems I had with the media and how theLa Haine and Assassin(s). The latter is probably the film I will be most proud of for a long time to come. I am part of an industry, and I don’t consider myself as an artist. Going to Hollywood was sort of like entering the belly of the beast. If you can get something out of it then good. What the trip gave me was wisdom - that the Hollywood thing was not something I wanted to do. You have to taste the fire to see if it burns. You cannot look at something from afar and imagine how it feels; you have to go there and try it.”

As well as Spielberg, Kassovitz claims as his mentors Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick. “All those guys,” he points out, “never made the same movie twice. So the best policy is to keep the ideas flowing.”

La Haine returns to BFI Southbank and cinemas UK-wide from 11 September. The film has been newly restored in 4K to mark the film's 25th anniversary, In November there will be a Limited Edition Blu-ray release. The restored version of the film opens in French cinemas on 5 August.