|

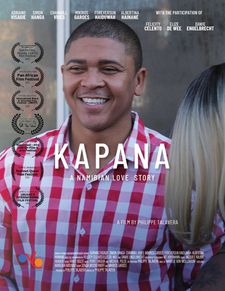

| Kapana |

Namibia has been in the news quite a bit of late, for reasons related to its troubled past, but it’s not often that its positive stories attract international attention. That’s partly why Philippe Talavera’s new film, Kapana, is so important. A love story focused on two men who meet in a bar one night, it’s screening at the Inside Out film festival in Toronto, and despite the boundary-breaking nature of the subject matter there’s a lot of national support behind it.

Philippe has had a slightly unusual route into filmmaking. He works for an organisation called the Ombetja Yehinga Organisation Trust (OYO), and that’s where this film originated. When we met for a chat as part of Eye For Film’s coverage of Inside Out, I began by asking him if he could tell me a little about it.

“First of all, we are an NGO, and what I do at that NGO is to use art to create social awareness,” Philippe says. “So all our projects have an art component. We do dance. We do some work with films, some with photography, some with magazines, and then we address different social issues. Originally, back in the day, we started on HIV, and then over the years we've worked on different social issues, from teenage pregnancy to gender based violence, to LGBTQ rights. And so basically, we identify the problem and then we try to see which medium would be the best to try to address this problem or challenge norms.

“Namibia is a country that is only independent since 1990. So as a country, it's only 31 year old. It was under German colonial rule, then it was British, it was identified as a South African protectorate, and along the way, it went by legislation on those values, from those countries. From the British, the very ancient law that sodomy is a crime. So the legislation is basically saying that you can't be gay. Interestingly enough, it doesn't talk at all about lesbianism, but it's condemning gay relationships, relationship between two men, or bisexuality as well.

|

| Adriano Visagie and Simon Hanga in Kapana Photo: Inside Out |

“As a result, a lot of people tend to be in the closet, to hide, to, to not express themselves and who they are. And sometimes they will actually end up marrying, is a family with with a woman, and others have that tension, that frustration, that loss of happiness. In terms of HIV, there are also quite a lot of unsafe relationships. So there's a lot of movement lately to try to challenge this legislation, and to try to challenge the status quo and to basically ensure a better, more equitable society. But as it stands, until the law has been repaired, it's difficult, because de facto, if you've got a relationship, you commit a crime. It's rarely enforced, it's rarely used, but it means that people don't tend to be open and don't tend to be out.”

So is it difficult to make a film on this subject in that situation?

“It was quite sensitive. We try to be as sensitive as possible. When we embarked on this project, one of the questions was, what is it we wanted? And right from the beginning I said ‘I would be interested in doing this project only if we get a positive story.’ So unfortunately, a lot of the best stories are problematic, about people hiding, people being infected, people not living their life, being frustrated. But then you don’t want to tell a traumatic story, you don't want the first Namibian gay movie to be something traumatic.

“So we were constantly getting in our minds the image of a young person somewhere that would see the film, and how could we bring a little bit of hope into that person's life? To know that he's not alone, to know that you can love and be loved as well. So we constantly tried to make it a positive approach. Then we did a lot of interviews with people from the local gay community, because there's a lot to try to find out. How do they navigate through this situation? Who do they tell, who don’t they tell, that sort of thing. So a lot of scenes from Kapana are actually based on real stories. We tried to keep it as realistic as possible.”

I comment that I like the fact that we see characters in a family setting where there's a lot of acceptance, and we also see a number of straight people in their lives who accept them as they are – characters who aren't often very visible in gay films in general.

“It was, again, because we wanted to try to keep it as realistic as possible,” Philippe responds. “We wanted people to like the characters even if they don't like the fact that they are gay, because we are in a country where it's very stigmatised again, so that at the end of the day they sort of can’t help liking George and Simeon. So that, by default we will like George and Simeon and by default we will want them to add up together, even if it's not what we believe in from, from the perspective of some of the viewers.”

Is it risky for actors to play roles like these?

“It depends what you mean by risky. Originally, at the auditions, quite a few actors didn't want to be involved in the movie. They were afraid about how it would impact on their image. So the casting was tricky. Because it closed door, some actors, which I would have liked to have in the movie, didn't want to be in the movie. For the others, of course, it was a bit of a gamble in terms of how would it be accepted, but I think generally speaking, our environment is quite supportive. So finding people who were interested in challenging the status quo and telling the stories of George and Simeon, that could be weird, but there were others who wanted to be part of it, and wanted to make a difference and wanted to talk about those stories. There hasn’t been really any backlash yet. Generally speaking, it has been quite well accepted by the immediate surroundings.

“An interesting factor, about Kapana is, to keep it quite sensitive about the topic and to be quite sensitive about the writing of those characters, we actually asked two women [Senga Brockenhoff and Mikiros Garoes] to write their stories. So this has been written actually by two female writers, and I think it was important to bring that sensibility to the writing of the story. I really enjoyed the way they brought those two characters to life in the writing, in the dialogues.”

|

| Kapana poster |

It’s the first time that Simon Hanga, who plays Simeon, has acted in a film at all.

“It was very challenging, I guess, as a first,” says Philippe. “But he took the challenge. He was really committed to trying to learn and to trying to change himself. We've got 12 different ethnic groups in Namibia and one of the groups that we most want to represent, they speak Oshiwambo. in that specific culture, it’s quite difficult today to be gay or lesbian. So we really wanted the actor playing Simeon to be Oshiwambo speaking. And Simon took on the challenge really well. It was not easy every day, but I think it was quite a breakthrough performance.”

I mention that I like the way the film explores the difference between people who are just looking for sex, which is maybe the more acceptable side of it, and people who actually falling in love – because there's a sense that it's socially okay to have a secret one night stand (which can always be blamed on drink the morning after), but it's a bad thing to actually feel something.

“Yeah, I think unfortunately the way it is in Namibia, because it is such a secret, then people have one night stands because it's less risky. It usually happens very quickly. Part of the problem is, where do people meet? There's no LGBTQI+ bar or club, there's no safe spaces. But also, because of the way people tend to live in Namibia, like many other African countries, you don't live alone in your place, you live with your family. So you don't go back home with your boyfriend. You don't go back home with your one night stand. So you’ve got to find a place where you can actually have an intimate relation and it’s so complicated. And that's why it’s interesting, the way that Simeon and George develop, that's when it becomes more than a one night stand, becoming much more complicated.”

The film also reflects on the stigma around HIV, which is a subject that OYO has addressed extensively in its work in the past.

“I think we have come a long way in terms of HIV in the media,” says Philippe. “But still, it hasn't been easy. It’s a difficult conversation to have. I think in that case, when you meet someone for the first time, unless it is your first love when you're a teenager, you come up with baggage. We all have our own histories. We all have our own past, we all have our previous relationships. And the question very quickly becomes, what do you tell on the first date? And what do you hide?

“In the case of a gay relationship, it often starts with a one night stand that is 10 minutes somewhere, and so you don't talk about those things. I mean, we just do it and don't talk too much. It's not a conversation. And then if you do it a second time, a third time...when does it become too late? And when it is it like that, even if you are taking precautions and you don’t put the other person’s life a risk, the secret becomes a burden. The problem is, in situations where you don't have a private space, how do you address this issue? Sooner or later, it becomes too difficult to say because you haven't said it the first time.

“So that that's not something that is just for a gay or lesbian relationship. When should we start talking? When do we start trusting the other person? When is the right time? And it's not an easy answer. It's something that we all have to navigate. How do we deal with our past? And what do we tell the person we meet In the beginning? What do we keep for later? What do we keep a secret? It's not so easy. And I think we all know that relationships are not easy anyway.”

It’s a lot to take on in one film, and of course, OYO faced other pressures as well. Having worked for NGOs myself, I note that there is never enough money. How did they get the budget together, and what was it like actually shooting the film with what they had?

“We got funding from Positive Action, which is in the UK,” says Philippe. “It was a very small budget by any means. We had a budget of 50,000 US dollars. It only works because a lot of people accept to either do the project on a voluntary basis or at a very, very reduced rate. We try to do it as simply as possible with what we have. But obviously it’s not a classic production. We do it with what we have, and we do best we can. What is important for us is to tell the story. And yes, technically it can always be improved. But what we have look at what we can do. It's a lot of goodwill from a lot of people that allows us to tell these stories.”

Though screenings so far have been limited due to Covid-19 restrictions, the film has found a warmer welcome in Namibia than might have been expected.

“Some screenings have been specifically for the LGBTQ community. So in some safe spaces with small groups we will have a discussion about it. At the big screenings we wanted to see what would be the reaction of people and what they would be talking about. Interestingly enough, last week we screened it in a township, and I had expected more reluctance from people. And actually, they were quite open minded. I was very surprised. They were quite understanding about what those two guys were going through, and realising it's not really right. Why do they have to go through that? So we had an interesting discussion.

“The whole point is not to just have film but to have a discussion. So that gives me hope, that people are willing to talk about and we need to, to accept that some people have a different sexuality. Some people have a different way of life and as long as it is consensual and as long as people are happy, why police it?

“I think every change starts with a dialogue, and until you have been able to start the dialogue, you can't make the change. So it won't happen overnight. But that's what we want to try to do, to have discussions and to make sure that people, step by step, start to reflect on this.”