|

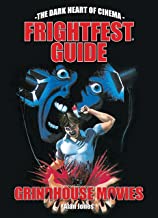

| The Frightfest Guide To Grindhouse Movies |

The Frightfest Guide To Grindhouse Movies is a beast of a book, its 900 grammes or so equivalent to a can of pop, a can of beer, and a bottle of hot sauce. From experience I can say it's an awkward read on a train, not as much from the copious quantities of painted-poster flesh as its unwieldiness as a tome.

This is perhaps a coffee table book, though not as bad as many of those Taschen works that are less book than coffee table. As someone who habitually carries a book to the cinema this was weighty enough that I did not bother bringing it when I went to see Prisoners Of The Ghostland at the Prince Charles off Leicester Square, though it would have been a spiritual Sargasso.

With a foreword by Jane Giles, whose book on The Scala is also out from FAB press, we're introduced to super fan Alan Jones. I'll mention Jane's tenure at La Scala (and the cinema itself!) ended in 1993 after a less than licit screening of A Clockwork Orange if only because the business of BBFC, video nasties, district council's control of cinema exhibition and the like all contributed to the atmosphere in which these were seen. The blue logos beneath the text do add colour and perhaps context, but I found it difficult to read in a variety of lights.

Differently difficult are Alan's 36 pages of introduction, cinema's role in his "deformative years". There's some context given on the cinemas of his era, though among the five 'T's of his definition of the grindhouse are missing five more - Timing, Transatlanticism, Tickets, Trouble and Translation.

That first he acknowledges, a golden era of the grindhouse. The second is discussed somewhat in terms of reactions to classification, Ebert's reaction to children in the audience for Night Of The Living Dead, the differentiation of distribution that meant some audiences got to see some films in some places and others didn't. The third the driving force, bums on seats, and sometimes in other places. That fourth dealt with in a jokey way at times, but tales of serial masturbators and pornography triple-bills make it clear that the surface of the grindhouse was often less veneer than venereal.

|

| The Horrible Sexy Vampire |

The last a personal bugbear. Many of these films are repeatedly retitled, screening in dark places of various descriptions. It would help perhaps to know that we're talking about Murder On The 17th Floor (see Angels Who Burn Their Wings), The Highway Vampire (see The Horrible Sexy Vampire), The Pills From The Pharmacist's Daughters (see Don't Tell Daddy), The Third Victim (see Mousey), and Love Story With Crime (see Vortex, or Blondy, or Germicide). Certainly if one is looking to find out if a given film is covered, or if there are pictures anywhere in the text of the film or its posters or stills.

The index is significant. By my count some 990 films are mentioned. There are 200 films in this work, perhaps as many in each of of the other four Grindhouse Guides: Exploitation, Monster, Ghost, Werewolf. Nothing indicates if a given film is in this (or any other) volume. Bold does indicate a page reference that is an illustration, but from the index alone you could not tell that Star Wars (six mentions) nor Black Sunday (five, plus one as Revenge Of The Vampire) have entries in the tome.

The former, you might think, of course, but many of these seem less grindhouse than films 'of the grindhouse'. In a personal guide its scope and nature let it down. It is neither exclusive nor conclusive, but those are among its strengths. Inclusiveness is not one of them, however, language used to discuss 'I Want What I Want' and 'The Woman Inside' discomfits. Trans issues are complicated enough without a tone that drifts from "too earnest to be exploitative" (p.169) to "the emotional rollercoaster of transexual experience" (p.232) before we factor in some notionally comic rhyming that drags up enough to worry about good faith. There's mention of promotional materials suggesting referring medical personnel to see The Christine Jorgenson Story (p.31) but even there the mild "as if!" seems to find ways to be cynical about what might have been cynicism.

|

| Black Sunday |

That 'of the grindhouse' includes others that were shown there rather than for there. It is described as a personal trawl through neglected corners based on Jones' own viewings so can be forgiven. Less in places where fact-checking seems to have been skipped.

The opening words for the entry for The Incident (1967) are "still banned in the UK" (p.114) but it isn't, it got a BBFC rating in 2014. "Too cringe-worthy for its intended audience" (ibid) and discussing the risk of copycats, the passage of 47 years saw it passed as a 12. Discussing The Power (1967) it's suggested that it "pre-figur[es] the comic strip blockbuster superhero/supervillain genre by at least 30 years". Ignore Batman (1989) or the similar Scanners (1981), the entry for Supersonic Man (1979) on page 228 mentions Donner's Superman. I won't rule out the line being laid at Orgazmo (1997) but I cannot parse the distinction being drawn. On page 207 1975's Infra-Man is described as a superhero movie, though it's a spiritual ancestor to Turbo: A Power Rangers Movie which also sits on that chronological fault.

In terms of availability there's an issue with The Spook Who Sat By The Door (1973), it was pulled from cinemas as discussed but it's on DVD and there's a television remake coming from FX soon. I was a bit confused that the entry for Survive! (1976) didn't mention Alive (1993) which was based on a different book about the same incident. There are other parallels, Amin: The Rise And Fall (1980) has the real Denis Hills, but The Last King Of Scotland (2006) might be more realistic.

|

| The Spook Who Sat By The Door |

Having recently read through the authorised biography of Terence Fisher I was surprised to see Incense For The Damned (aka Vampiros Del Terror) (1971) mentioned as a pet project of his, but checking it would seem that it's a rumour too far as under the title Doctors Wear Scarlet there was "no evidence of this in any of Terry's Paperwork" (Terence Fisher: Master of Gothic Cinema, p.447). Neither text is kind about Sherlock Holmes And The Deadly Necklace though, which is fair.

If this seems the picking of nits it is perhaps brought about because of production values. This is for fans, true, but it's glossy and girthy and generally fun. I'd hesitate to use it as a reference because it set off enough alarm bells that I did start in on checking, and much of that was done hunched a train where I was travelling to its terminus. It makes much of being based on Jones' own diaries, and while I don't doubt much of the reaction is contemporary it'd be nice to get a sense of the whens and wheres. That might though require a different guide, not to the movies thereof but the grindhouses themselves.

This is pleasant enough to read, but there's not really a thesis to it. These films exist, might be considered to be neglected, the author of the book has seen them. Four volumes in those who are Frightfest Guided will know what they are getting themselves in for, for those of us not aboard this is not an ideal jumping on point for genre ingenues or those not already embarked upon the cruise.

The Frightfest Guide To Grindhouse Movies, by Alan Jones, ISBN 978-1-913051-11-2, is available to buy now.