|

| Death And Bowling |

X (Will Krisanda) is a member of a bowling league, but he knows next to nothing about bowling. it’s a lesbian bowling league, and he’s a man, but his experiences as a trans man bind him to this community. When team captain Susan (Faith Bryan) passes away from illness, X finds himself suddenly adrift, and embarks on a strange journey through grief that will remind him of the value of his chosen family and also bring him close to a stranger, Alex (Tracy Kowalski), who appears at the funeral. Death And Bowling is a curious, offbeat film which challenges the conventions of trans representation onscreen – not least with its opening scene, in which X, an actor, performs a tragic character death with the aid of an unlikely stunt double. This seems a long overdue swipe at the kind of roles trans people are given, I suggested to director Lyle Kash when we met in the run-up to Newfest.

|

| Lyle Kash |

He nods. “Yeah, exactly. And I also wanted an opportunity to have a bit of a documentary element. Something that will extra textual to the film is that all of those crew members that are acting as crew for that shoot, that's my film crew, they weren't actors. So it was an opportunity to get the almost entirely trans crew in front of the camera.”

I found the trans cast interesting, I say, because they look like real people – there’s no particular effort to be glamorous or to ‘pass’, they’re just being themselves.

“It was really important to me to have trans people who were recognisable as trans to me and to other trans people on the screen,” he says. “You know, part of what interests me about the casting and how I wanted to set it up is that it's so obvious that you're looking at a screen full of trans people whether or not you recognise every individual is trans. but the only people who are described within the film as trans are Alex and X. So there's a way of reading the project or reading the story as this entire magical world in which everyone is trans or there's a bunch of trans people playing cis characters or ambiguously gendered characters like this, but even in the casting and as we were doing the edit, there were times where collaborators or people in the industry were telling me ‘Okay, you need to boost the saturation on Alex's scars, or people won’t register that he’s trans. They won’t believe he’s trans when he takes his shirt off.’ No. We need to see that people look trans in a broad and expansive way, and maybe also like the audience isn't entitled to know who's trans or not. That was an important piece for me.”

One of the things that I find odd about cinema more generally is that we hardly ever see trans people who are just there in the background, incidentally.

“Yeah, it's also that's just what my world looks like. So to express that on screen, I mean, people say – because of the stylisation, that's probably more what they're speaking to – people always say it’s just adjacent to reality.”

I've seen people describe it as magical realism.

“Sure,” he says. “I'm attracted to magical realism. But I definitely wanted to keep the film within the realm of fiction, and pushing it in a sort of surreal direction helped with this, but so much work about transness is either documentary or it's fiction. It feels almost ethnographic, like we're asked as trans filmmakers to provide authenticity, accurate representation, positive representation, and I think we sort of lose on the potential of imagination, trans imagination, and I really want to insist on the possibility of transness existing in a fictional space. So pushing in this sort of surreal direction, I think, keeps reminding people you're not watching a documentary and this isn't supposed to be teaching you about some reality about trans, this isn't an educational work. If people learn something from it, beautiful, but that's definitely not the goal.”

|

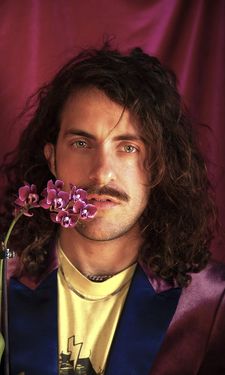

| “I'm about as good at bowling as my characters are" - Lyle Kash Photo: T4T Productions |

Something that interested me about the general story is how it looks at how outsider communities deal with death. That seems particularly important at the moment, when so many people have lost loved ones due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

“When we started writing the story, the pandemic had not begun,” he says. “By the time the pandemic set in we had a screening event scheduled that was cancelled, a year and a half ago. It's an unhappy but sort of interesting accident that the film deals so much with grief and loss in this way and how community responds, but yeah. How I approach how I approach dealing with grief in the film, it's like, that's maybe the autobiographical part, I wanted to show what queer family looks like. Even with the traditional structures of a mother and a child, what does it look like to have a community respond and to hold someone through grief and include trans community? I think it's often the case that we don't rely as much on our biological families as we do on what to other people might look like community, but to us looks like deep, hardcore family.”

People build community around a lot of different things, so was there a particular reason why he chose bowling?

“I'm about as good at bowling as my characters are,” he laughs. “I was dealing already with stages of grief. There were a few things that led me towards the bowling alley. One, I wanted a space that could sort of rationalise the heavy nostalgia that I'm attracted to stylistically. It's deeply American, a deeply American pastime, but it's also a space that can have this retro feel, and then capture what I see as sort of an aesthetic of the generation of the older women who are in the bowling alley. It also looks like nostalgia that I think contemporary queer people are stylistically putting forward in art and in clothing. And I think a lot of us are really attracted to the queer art of the Eighties and Nineties. I wanted to incorporate that in the contemporary piece but still have it have a relevance to the world we are creating. And then, you know, even X says this when he's introducing himself: the three holes of the bowling ball that are really perfect to talk about trans men, so that really clinched the deal for me.”

|

| Spending time with Susan Photo: T4T Productions |

The bowling alley gives us a very specific interior space, and then the film takes us out into the desert, and suddenly there's all of that space. Was that a way that he wanted to talk about some of the opening up of character and possibilities?

“Yeah, especially for Alex's character. I think there's like a transformation moment, especially in that shot where the camera comes down and he has a change of perspective. I did want to open things up. Both spaces, the desert and the bowling alley, feel like spaces of grief or they evoke some some type of grief, I think. The expanse of nothingness that a desert offers is one form of this, but also in a bowling alley. It's one of the few spaces besides looking at the ocean, like when people go to the beach, or they go to the movie theatre, where everyone orients their bodies in one direction and looks at a horizon and I think that that also, for me as an artist, evokes that sense of grief and also desire. There's a space that you can't enter. You toss the ball, it returns to you, but there's a horizon that everyone gazes at. And I'm interested in spaces where we know to culturally do something but we don't think so much about it, but we all orient our bodies in space in a particular way.”

With all those complicated emotions at play, there’s a lot of uncertainty in the film, and it doesn’t follow any conventional Hollywood framework. Was he looking for a structure which reflected the theme?

“Yeah, I mean, I think I'm also I'm attracted to film that does that. To make the film formally trans. I mean, I'm looking for art forms, or for formats for trans cinema that move away from linearity. I don't think that trans lives are particularly linear. I don't think the way that we tell stories can be told linearly and often they are, it's like a before and an after. And, you know, you make a decision and then you're supposed to cross and then you reach a destination. I don't actually think like anyone's lives look like that. But particularly, I didn't want to tell a trans story in a way that had a simple ending because I think gender needs to remain open ended and we need to transition in a more messy, complex way where you can read it in multiple ways. You can imagine that X gets the happy ending or he does not We don't know whether the final scene actually happens. So I wanted something that could be sort of cyclical, open ended, a little elliptical. And not tie any neat bows at the end.”

|

| Telling it like it is Photo: T4T Productions |

There does seem to be an assumption, amongst a lot of cis people, that trans people are unhappy until they go through a magical operation which transforms them, all in one go, into people who will live happily ever after, and real life is just not like that.

“Yeah,” he nods. “And that's also why I cast two adult trans men who are well past this moment of the decision making process around like, coming out, to transition or not. I just think so much trans work is about coming of age, and that's very beautiful. But we need the genre to expand.”

That seems to have provided him with space to explore masculinity and different ways of growing into a masculine social space. “Yes, totally. And I think, you know, X’s character maybe is not so self actualised. But Alex has a sense of life where he can reflect and even embrace ‘Okay, I loved being a girl, I'm just not a woman.’ I think it's a very complex position that, you know, a teenager coming into transition might not be able to articulate in the same way.”

It’s something that I think comes out with the narratives around death in the film as well, I suggest.. There's that sense of things being valuable even when they're transitory. And that being something that that isn't addressed very much in film, because there's always this idea that you reach a perfect state and then you stay there.

“Completely. And Susan never really leaves the film after she dies. Obviously the film is a bit sad in parts, but I don't think the tragedy hinges on the death. If anything, her character's the driving force throughout the film. We even see her on screen a number of times through people's memory and that presence. Yeah, I wanted to speak to the fact that there's not a before and after in any of these categories.”

So how did the film come together in terms of funding and organisation?

“It's a deeply community grown project,” he says. “We had a $75,000 Kickstarter that we successfully fundraised the summer before we shot the film. So yeah, it was all community funded and a lot of people volunteered their time to work for very little. I mean, this is the story of all independent film. But really, the film came together because a lot of people believed in it. I think people were very hungry to participate in a project that was made by trans people, and could involve this sort of moment where a ton of trans people came together.

|

| "To us looks like deep, hardcore family" - Lyle Kash Photo: T4T Productions |

“I always think of Agnès Varda, who's one of my favourite filmmakers. She's thinking about the filmmaking experience itself being the art form. With her film Happiness, she essentially wrote an entire film about picnics so that she could spend the summer shooting with her friends at a picnic. And I think that, for me, this is sort of a trans picnic. Like, how can I create a scenario also where the beauty is that we all came together for six weeks and got to be around pretty much exclusively queer and trans people, to make this project? So there was some magic that was offered by the film itself and the making of the film. The film wouldn't have been possible unless people had given a lot of their time in a way that, you know, maybe an industry film would not have asked of them.”

I’m reminded of a conversation I had with Bao Tran a couple of years ago, where he said that he found it hard to get support from studios for a film with Asian American leads because they would protest that there weren’t any Asian American stars. He felt that in that catch 22 situation, Asian Americans had to make their own stars. Does Lyle think that the same is true for trans people?

“Absolutely. And I think also, artists need to start insisting that we don't need star power in our films that we make. Independent American film doesn't need to just look like cheap Hollywood film, it can actually be a different art form itself. And I think once you free yourself of that need to get star power, to get people to see the film, if we offer something else, if we offer something magical that Hollywood film can't offer, I think we will be less pressured by those demands for stars and having to have famous trans actors, I'm not really interested in making trans people famous. I’m interested in trans artists being able to make work and I think those are different goals.”

That certainly accords with that the organisers of LGBTQ festivals tell me, when they’re looking for films with fresh narratives. How does he feel about being at Newfest?

“I'm very excited to show the film on the East Coast, finally. Also our premiere at Outfest was magical. I mean, I feel very lucky to have been able to largely fill theatres during the pandemic, I think it's really important that people who can, go to the theatre and sit in the seats, despite the virtual offerings that are going, because it's a really important barometer for independent film, even in a moment like this. But yeah, I mean, after Outfest, we've begun to schedule a pretty robust festival run. And I just feel very humbled and proud about the film and excited to get in front of queer and trans audiences. So of course, those people are at the LGBT film festivals. And it's just beginning. It's very, very special.”