For the 87th Academy Awards, Germany’s Oscar submission was Dominik Graf’s Beloved Sisters (Die Geliebten Schwestern). Poland’s entry Ida, directed by Paweł Pawlikowski won the Oscar. Graf’s latest film Fabian: Going To The Dogs, co-written with Constantin Lieb is loosely based on Erich Kästner’s novel Fabian Oder Der Gang Vor Die Hunde and stars Tom Schilling, Saskia Rosendahl, Albrecht Schuch, Meret Becker with Michael Wittenborn, Petra Kalkutschke, Elmar Gutmann, and Anne Bennent.

At the German Film Awards, Gold wins went to Hanno Lentz (Cinematography) and Claudia Wolscht (Editing), and Silver to Fabian: Going To The Dogs (Outstanding Feature Film, produced by Felix von Boehm).

Many films tackling the Weimar years make what is to come unavoidable in hindsight, as though the warning signs gave only one direction. The way Dominik Graf treats time In Fabian: Going to the Dogs, treads on much more dangerous territory. Cabarets and nightclubs and brothels are booming. Bodies are on display out of pleasure or despair or both. Jakob Fabian (Tom Schilling), with a doctorate degree in literature in his pocket and a job as a copywriter of cigarette ads which won’t last too long, comes across as a visitor in his own life. His friend Stephan Labude (Albrecht Schuch) just submitted his thesis on Lessing and the two celebrate in one of the decadent establishments of the city when fate steps in and Fabian meets and falls in love with Cornelia Battenberg (Saskia Rosendahl), who plans a career as film lawyer and/or movie star at the studios in Babelsberg.

We are in Berlin, summer of 1931. A year after Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer’s film Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday; story by Billy Wilder and Curt Siodmak, Fred Zinnemann as cinematography assistant) came out. The world of Fabian is not a picnic by the lake, although it includes that as well. Inflation, unemployment, the wounded bodies of those who managed to return from the war mark the times.

From Munich, Dominik Graf joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on Fabian: Going To The Dogs and Erich Kästner.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Let’s talk about Kästner and Fabian. As far as I know, the uncensored version of Fabian was only published in 2013. Did you read the novel then? Has it been a project of yours since 2013? Did you like Kästner before? Tell me about how it all began!

|

| Jakob Fabian (Tom Schilling) with Cornelia Battenberg (Saskia Rosendahl) |

Dominik Graf: We Germans, we all like Kästner. Because we read him when we were children. We read Pünktchen und Anton [Annaluise and Anton], we read Emil und die Detektive [Emil and the Detectives], and Kästner is one of the favourite authors of all times in Germany. But Fabian is something unknown in a way. There was always a battle about this book. It nearly didn’t come out, then the editor wanted to erase some parts of it. It came out censored, but Kästner wasn’t content with it. So after the war we had one director who tried to film it, Wolf Gremm. He did it in 1980, but he did the old version, so it was a bit of a West Berlin playboy version of Fabian.

Then in 2013, as you said, the new version came out. It’s not that much different but it has parts in it which are very strong, very severe also with German society at the end of the 1920s. I took interest and at the same time, I didn’t know that, a producer took interest, and Constantin Lieb suddenly started, I think he didn’t have the rights, to write a script. I read that script in 2016 or 2017 and was immediately on fire. So we finished the script together so we could shoot it in 2019.

AKT: The start of your film at the subway station feels magical, because it has three time levels you put us through. We don’t time travel just once. First, the architecture places us in the past, undefined, next we see the passersby and we realise we are in the present. Then comes the ascension: You have to go up, not down, to end up in 1931. It’s beautiful. How did you come up with the idea?

DG: That came by accident. The producer tried to make the Heidelberger Platz, which is a subway station in Berlin, a location for me. So he went down with his new camera; he was very proud of carrying through the whole station and in the end up. And I saw that and thought that is not only a very good location, that is a very good shot. That’s how the idea came. It was a difficult shot. I think we shot it on the last day in Berlin. It is quite difficult. We had some extras who were blocking some POVs but of course we also had people saying “What’s going on here? I get out of the subway and see a camera looking at me?” So we had to do five or six variations of it. In the end it worked and it was a heavier camera than the producer had when he tried it at first.

AKT: What is the name of the producer?

DG: Felix von Boehm. Lupa Film.

AKT: Architecture is throughout the film very important. Houses, the murals of the four seasons that we see over and over again. And the wonderful statues, the caryatids, that hold up the buildings. The women holding up the architecture of the time. The past is still present in stone. I would like to know what you were thinking.

DG: The idea was not having a sort of expensive costume movie, but making a sort of montage all the way through, so that you cut, you edit the times together. You edit this figure on the wall over there with a door over there. We shot in Görlitz, which is a place in East Germany, former East Germany, well it’s still eastern. And we shot in Berlin and we put the two cities which are so completely different, together in a way that maybe you can’t tell where is what, so to say. The feeling for the audience should have been - there was a lot of breaking down in the Twenties. Houses where the doors are shuttered and the windows.

There is also the style from the times before the First World War. And it all comes together with the pain that still lies in the atmosphere after the First World War. Fabian was in the war, his friend Labude was in the war. The whole situation had to carry something painful. In a way, the past is blocking the future. But nobody knows yet that the future will be much more terrible than the past.

|

| Jakob Fabian (Tom Schilling) with Irene Moll (Meret Becker) |

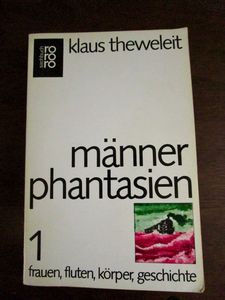

AKT: That’s where the imagery of water and floods also comes in. Two things made me think about Klaus Theweleit’s book Male Fantasies. You have the notice in the paper about the biggest storm coming to the Baltic Sea and there is the poem that Fabian writes about the train racing through the years. On Theweleit’s book cover is an image of a train going through an ocean and I suddenly had to think about that. He discusses the same time and the males of that time.

DG: I mean, what Theweleit has written about the fate of being a man in western culture very much impressed me when the book came out. I read it and I found it immediately on point. It hits the point that we are in a way imprisoned in a picture of ourselves, many of us are, which we can’t get rid of. There are many explorations about the males in the times of the World Wars. The picture is yet … There is no softness, there is nothing left for being and to lose. All the time we have to win, we have to break through. This image that you just mentioned, showing a useless power demonstration, which is very much part of male self-identity, I think.

AKT: Which brings us to Tom Schilling. As an actor I always felt him to be ill at ease in the 21st century and equally ill at ease in the 20th. As if he belonged to neither fully. Is that why you chose him?

|

| Cornelia (Saskia Rosendahl) takes aim at Stephan Labude (Albrecht Schuch) |

DG: Well, I always wanted to work with him. With Fabian the point is really that I wouldn’t have done the film if he had said no. He is so much this person. He was so close to my imagination. I read Fabian for the first time at the end of the Seventies and then again of course when the new edition came out. And immediately Tom’s image appeared before me. He couldn’t have said no.

I really urged him to do it and it wasn’t easy all the time because Kästner and Tom, some things … There is the German word “Anstand” [decency] - it’s something between politeness and moral conviction. So you have to be “anständig.” It always appears in the book, again and again and again. In an ironic sense, as well as in a real sense. “Wo ist der Anstand?” Where has it disappeared? And Tom asked; What is this? I don’t know what he’s talking about! We had to come together but at the end I’m very very happy that he accepted the part.

AKT: He is perfect because he is swimming in the situations. You cannot pinpoint him. He’s not one thing.

DG: He is a wonderful flaneur, somebody who’s just looking, just walking by. Oh, what’s over there? Shall I do something? No, I don’t. It’s better I don’t. And when he finally does something, he dies.

AKT: Which is the irony of it all. By the way, you like making films about writers who can’t swim?

|

| Dominik Graf on Tom Schilling: “I read Fabian for the first time at the end of the Seventies and then again of course when the new edition came out. And immediately Tom’s image appeared before me.” |

DG: Ha! In the 18th century it is a fact, nobody could swim.

AKT: So Schiller wasn’t the exception?

DG: The shout of the sisters “Can you swim?” is completely useless because nobody could at that time. But in the Twenties already, did you see the posters everywhere on the doors? Everyone goes “Learn to Swim! Learn to Swim!” Because we now again have very many casualties of those not learning to swim. But in the Fifties, we tried to learn it. We didn’t learn it between the wars.

AKT: A performance I especially liked here, he was also in Beloved Sisters, is by the actor who plays Labude’s father. His variety and depth are marvelous in this role.

DG: Michael Wittenborn, yes, I’ve worked with him very early in my career already. We knew each other here, he was at a theater in Munich at that time. With Beloved Sisters we revived that relationship. There’s something in his play which is so sensitive and there is so much nervousness in it in every moment. I really like that. He’s great.

AKT: The actor who pays Labude, Albrecht Schuch, at certain moments reminded me of Carl Raddatz, I can’t really tell you why. I recently watched [Veit Harlan’s] Opfergang for the first time and was quite blown away by it.

DG: By Raddatz?

|

| Jakob (Tom Schilling) with Cornelia (Saskia Rosendahl) at the lake |

AKT: By Raddatz.

DG: Yeah, it’s an amazing movie.

AKT: I knew him from [Helmut Käutner’s] Under Den Brücken.

DG: I once wrote something about Raddatz because for me he is a sort of father figure. He came out of all these Nazi movies untouched and he continued working in the Fifties and the Sixties. He had this ease. Everything was in a way at ease. Everything was smiling. The difference with Albrecht, who has also this male natural behavior is that Albrecht when he laughs, there is always a sort of desperation in his laugh. It’s not real, it’s always a cover. “Everything is okay, isn’t it? We have a good time, don’t we?” Like the “don’t we” is bigger than the thing. Fate hangs upon him very heavily and this is what Albrecht can do very well: feeling maybe at ease but he isn’t at ease. Something very much is pressing him.

AKT: I can see that, yes. Your decision to have two narrators, one male and one female, is very interesting. The narration always is soothing, although it tells of strong things. To have two, one might think it could be disturbing, but it isn’t at all.

DG: I hope, yeah. The thing is, when I make a film after the work of such a big and famous author as Kästner, such a good author also, then I want to have the text, the lines, the writing in the film. I don’t want to have just scenes taken out and take a bit of dialogue and invent the rest. I want to give the feeling of this very special, very witty language of Kästner. So I chose a speaker [Joachim Nimtz] who sounds very much like Kästner himself.

|

| Cornelia (Saskia Rosendahl): “The costumes had to give a sort of freshness of feeling new …” |

Kästner played the narrator himself in a few of his children’s movies, so you know how he sounded. In a way this narrator gives a feeling of being from Saxony, being old, being experienced, as he looks back at his own youth when he narrates. On the other hand I had the feeling that there must be some kind of voice in it which speaks from even higher above, as if Greek gods were to tell the future. You don’t know yet, but this will happen to you. But still you don’t know. Jeanette Hain’s voice, I used her very often with this strange reciting voice which is beautiful and cold in a way. So these two ways of telling are very different and that was something I wanted to profit from.

AKT: Her voice from above is perhaps that of the caryatids, holding the buildings up?

DG: Yes, that’s cool, that’s cool. The caryatids are also figures that are very much in this film, this drama, because they are still holding the world together, in their hands, on their shoulders. But we all know it will fall apart very soon.

AKT: The moment when we see the Stolpersteine makes it so clear that their future is our past. In one shot. The costumes [by Barbara Grupp] puzzled me. I wasn’t really sure what your intentions were. In many moments it’s clear that we are not to believe this is 1931. Cornelia’s shorts with the shirt could be now; when she is wearing the white pantsuit it is more 1980s than 1930s.

DG: We also used punk music in the beginning. I think that these kind of troubled times, difficult times, they all fit together in a way. You can jump from these times to today. I don’t know if we have a troubled time in Germany at the moment. Well yeah, there’s something that fits a bit to the late 1920s, I think. So you can use them and mix them together. They all give the same feeling of turbulence and also the positive: invention.

|

| Fabian: Going To The Dogs poster |

The art development in the Twenties was enormous, of the film development and so on. In it is everything at the same time. You have the feeling that could be too much sometimes. I think in the Seventies and the Eighties it was a bit the same, we didn’t always look at: is this documentary-wise right or is it maybe from a different time? The costumes had to give a sort of freshness of feeling new and you don’t have the feeling that you’ve seen all those costumes in the last costume movie.

AKT: I sometimes like when costumes speak of two eras at once, for instance Polanski's Chinatown, where the costumes reflect the Seventies as well as the Thirties. [See my conversation with costume designer Ann Roth on that subject] There could be another connection to [Josef von Báky’s] Münchhausen as far as the chaos is concerned? Time travel and lots of different elements and of course the Kästner connection [who wrote the film script under a pseudonym]. Did you think about Münchhausen at all?

DG: No. The Münchhausen film isn’t quite near to me in a way. I mean, I like films like Veit Harlan’s Opfergang, even though they are said to be Nazi movies in a way. Münchhausen, yes in a way it was funny, but there’s something too proud, it’s too much exposed by the system. There’s too much money in it and too much showing off what we can do in the Nazi film business.

AKT: That’s not what you do in Fabian at all.

DG: No.

AKT: One last point. Crème Bavaroise becomes an enchantment. From a dessert it turns into a spell. Say it three times! What is that scene about the magical Crème Bavaroise?

DG: I think she hears the word and then she tries to train her language. Oh, this is a difficult word. I want to be an actress, I should be able to say it. So she exercises Crème Bavaroise, Crème Bavaroise. Then her mouth becomes more fluid in a way. It is a funny expression.

AKT: Thank you very much.

DG: It was great talking to you. Thank you.