When we caught up with González over Zoom to talk about the film, we spoke about the origins of the project and his move from documentary to fiction features.

“The town where we shot the film is where I grew up and I'd been making films there for a bit already, but I'd never, let's say, tackled or talked about these issues regarding the tequila industry, because it's so omnipresent in my hometown - it's been there for so many years, for centuries, actually,” says González “It was just difficult for me to have enough distance or perspective to talk about it. My family is also involved in that business since it wasn't a business, since like, the 19th century or so.

|

| Juan Pablo González: 'What I liked about making this fiction film is that it kind of freed me - my documentary thought process kind of got a little bit more free' Photo: Courtesy of Cinema Guild |

The filmmaker says the film was a long time in the preparation and the making, but that he welcomed the greater freedom that a fiction framework offered him.

“I started thinking about this character a long time ago and it was probably 2013 or 2014 when I met Teresa and I felt like, 'Oh, I think she could play this character that I've been thinking about'. There are characteristics of these people that I know blended together into one character, and the only way to do that, I thought, was to make it into a scripted of fiction character. The other thing that I wanted to do was to have the freedom of shaping this character and to try to strip away some of some of the stereotypes that define what, in Mexico, people call provincial business owners. That word 'provincial' in Mexico is used everywhere. But in academia, I feel like it's used in one way, and then the way it's used here is like everyone who lives outside of Mexico City, just anyone who is outside of Mexico City is a provincial person. That's the sort of jargon that is used to define 80 per cent of the country.

“So I started thinking about the character in 2013/14 and then it took me four years to actually say, 'Okay, I think I'm ready to begin writing this'. It was when I was making my first feature nonfiction film, Caballerango, that I started writing this film. I started writing with two collaborators, one is my wife and then we found another writer, which was really good.That was the summer of 2017.”

As a documentarian, a director is generally following wherever the action takes them but with fiction there’s a lot more control and a need for artistic intent. González says that some of the secret to succeeding with this first fiction feature was admitting what he didn’t know from the start.

He adds: “My approach to it was, I didn't know how to make fiction. I was very clear with everyone - I don't know how to direct actors. I was trained a little bit in that in my graduate studies but none of the techniques or processes that I learned really worked for me, I didn't really connect with them. So what I did maybe to protect myself emotionally was that I just presented myself as someone who actually did not know what I was doing. I was just like, 'We don't have to feel like we're professional fiction filmmakers making a film and I have a vision, and you follow that vision'. It was more like making everyone feel comfortable about being uncertain and maybe not fully knowing what they were doing in their own departments. I feel like that was very important for everyone.”

I wonder if, as well, working in documentary has made González more patient and aware of everyday rhythms that he has gone on to incorporate into Dos Estaciones, which features both moments of stillness in which we watch things like the mechanics of the tequila factory juxtaposed with more intense scenes, including kids creating piñata chaos at a birthday party.

“It's so interesting to think about rhythm and time in cinema, like how we capture it, but then how we present it,” says González “How we manipulate it through the camera, but also through the editing, and through the kind of sonic spaces that you create in a film. That is something I'm really interested in because I am capturing this place that I grew up in, that seemed slower than everywhere else, but at the same time there is an intensity to it, in certain moments of the year or the day, even. But how do you capture and then present that in a 90-minute film? I love to be patient in my films but I think this idea of rhythm, and the manipulation of rhythm is also really important for me. Because it speaks to a certain complexity of a space. The way rhythm and time are lived in a particular place expresses a lot of what that place is, and expresses a certain complexity and a contradiction, so you think, 'What is the experience of the space like?' - that question is really important to me.”

The documentary work was useful in terms of helping him to explain to his director of photography, Gerrardo Guerra, who was also making his first feature, how González wanted various scenes to look but he still had to learn new techniques.

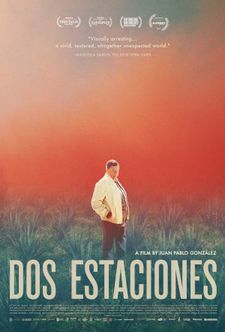

|

| Poster for the film |

Going forward, González is continuing to work on new fiction features but also has some ideas for factual films up his sleeve.

He says: “I'm currently working on two scripted projects. What I liked about making this fiction film is that it kind of freed me - my documentary thought process kind of got a little bit more free. So now I'm thinking about making nonfiction work that's maybe more non-character based. There's a lot of things in my region that I want to explore. Now I'm living here and the more I'm here, the more I see things, the more I learn and relearn the history of the region that I'm interested in. So I'm working with both. The fiction work that I'm doing is also very grounded in things that are happening around me.”

In the second part of our interview we talk to González in more detail about the portrayal of Mexico on film, avoiding stereotypes and presenting gender fluidity.