He says: “I always wanted to have time to sit and just go through all the Hollywood films and when a character like a US American character arrives at a small Mexican town, there's like a Spanish guitar playing and there's like a boss.”

And it’s not just Hollywood stereotypes González takes issue with. He adds: “Another thing that I really struggle with in Mexican cinema is again, this centralist kind of tradition of bringing actors from the capital into the provinces and faking accents. It is very common in Hollywood, I don't know, to be honest, like how someone from Appalachia feels about these Hollywood actors coming and then speaking like them.

“But I've always resisted that and I've always been very aware of it. So I wanted to have as many people as I could from the region because it's a different type of expressivity. It's not about trueness or reality or realness, I feel like it's about a certain type of expressivity that people have when they grow up in different regions, and especially if they grow up in a region and then live their lives in those regions, so it's very particular.”

In order to achieve that, the filmmaking process was a long one, which began a long time before the cameras actually started to roll. Adopting a collaborative approach, the crew would go to the region with Teresa - who is not originally from there - every year for a week or so in order for her to really get a feel for a place.

He explains: “It was quite a lengthy process. We would raise a little bit of money to make a trip. It was a very small crew and we are all documentarians, so I know how to do sound, camera, we know how to do all those things. So we'd come with Teresa most of the times. A lot of the work with Teresa was thinking about how Maria would move and speak. I didn't want to put too much pressure on that but she knew that this accent and this expressivity was very important for me. So I just told her Maria is from Mexico City, and then you move to Morelia, you've been living in Morelia for 30 years. So let's just create that kind of background for the character, like you are from this town, but then you went and studied in Mexico City, and travelled a little bit, and then you came back and let's kind of build a character from there. But also, her being in that space and being in communication with the people from that place so much allowed her to capture a lot of what people there kind of feel and express.”

Ahead of the main five-week shoot there were three or four smaller shoots across the three or four years when González and his crew visited. They also had an acting coach to help the non-professional actors - most of the cast - with their roles.

González says: “The acting coach was amazed at how everyone just needed three weeks, when sometimes this process of coaching non-actors takes months. With them, it was just a few weeks. Then we were very flexible with the script. It had all the structure of the film but we agreed on getting rid of the dialogue for when we presented the script to them. It was all just actions.”

He adds: “We knew it ends up being quite a sort of melodramatic film and we wanted to express this melodramatic arc of this character but at the same time, the everyday was also very important. That's why the film digresses, it holds back because what we what we talked about with with the actors is let's just create these dialogues in this moment that kind of express whatever you know, whatever you would do on a normal day, but then there was always the element of the plot in each scene.”

Gender identity is very fluid in González’s film, Maria strikes up an intense relationship with a woman (Rafaela Fuentes) she takes on to help her with the plant and she also has a transgender hairdresser (Tatín Vera), whose character we see going about her day-to-day business in the town.

“It was a little bit of a coincidence of having met Tatín Vera and just wanting to work with her,” says the director. “We met while I was doing another film years back and we talked and we became friends. There's this belief that these regions are culturally super-static, and that gender roles are absolutely defined. I feel like that is one of the biggest misconceptions of these places. I don't, I also don't want to excuse a lot of practices that are very exclusive but I feel like gender roles are a lot more fluid in this region than people think about. And the fluidity is complex, it's not like, you know, how American liberals want to define it - it's not that discourse.

“Tatín, for example, is very in tune with a lot of the conversations that are happening in the US and Europe, but then she's also super-Catholic. So it's complicated, and I wanted to show Tatín not just as a trans woman, but also as a businesswoman. She is actually a hairdresser and has this business that is thriving. She has clients from all over the US, she makes appointments like a month in advance. I wanted to show a character like that because it's not usually what you think of when you think of these places.

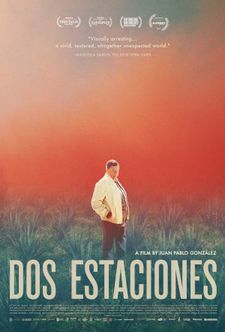

|

| Poster for the film |

He adds: “It was really important for them to have an intense, close relationship. And a relationship that was kind of tense and that led to, you know, many interpretations of the film and I think that's good and healthy for the film. I think something that's important to note is that that relationship was something that we built together with them. Teresa took ownership of that character and made it what it became. There's some sort of explanation in the film about why she's a more quiet, tough woman, because she's had to put up with a lot of shit.”

Dos Estaciones opens at IFC New York today, September 9, before rolling out across the US. It will also screen in the Horizontes Latinos section of San Sebastian Film Festival later this month.

- Read the first part of our conversation with Juan Pablo González, in which he talks about moving from documentary to fiction directing and the origins of the film

Watch the trailer: