Sierra Pettengill’s documentary Riotsville, USA, draws on archive footage to consider the development of fake towns - constructed from facades - that were built in America as a response to civil unrest in the late 1960s. The concept was as a training ground for law enforcement but, as our reviewer notes, they were “one-dimensional towns trying to solve multi-dimensional problems”. As the archive shows, these places were highly talked about at the time but have since drifted from memory, Pettengill brings them back to life, considering the militarisation of the police force and the interplay between that and racism - a process that arguably continues to this day. We caught up with Pettengill ahead of Dogwoof’s release of the film in the UK this week.

You’ve said you came across the idea of the concept of the Riotsvilles in Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland. - how surprised were you when you first sort of encountered the idea?

here] and all sorts of covert programs, not to mention what we did in Latin America. So, no, I don't think I was surprised that this kind of thing existed. I guess that was the main challenge for me in this film, it had to be more than about this specific programme. Riotsville is a symbol of something, as well as being a very literal part of history. And, and in that way, Rick Perlstein’s framing - he doesn’t talk about it, it's just sort of in a list of things - but where it comes in his book, is after a commission convened in Newark, after their uprising and 67, and I'm paraphrasing here, but their conclusion was either we can choose reality, or we can choose illusion. And he says, the public was choosing illusion. The film is tracking what it means to to triple down on an obviously failed policy.Did you find your experience of being an archival researcher helpful, because I imagine that when you came to this, there was an enormous amount of footage? You’re not just talking about riots, it's a much more contextual film than that.

SP: My way of making films is through the archive, and that's my way of understanding the world I'm living in so it's hard to extricate directing and research for me, they're the same thing. I was researching all the way through the edit until the very, very end, trying to find new material. In some ways, how it's constructed formally replicates the process of understanding and making my way through the history and the material.

I want the history to feel open for us to be using as material for the present and the future. I didn't want it to feel like a closed document, it needed to be open. Part of the way of trying to communicate that is having my fingerprints all over it, having the editor’s fingerprints, having our writer and our composer - I wanted it to feel very constructed.

There’s deliberate glitching in the film, which draws your attention to the fact that you're watching something that is, whether archive or not, is still constructed by somebody else. So leaving those kinds of fingerprints on is important to you?

SP: Yes, because I don't know what the point of making a historical film is, if not to invite people to use this history as a blueprint, or a model or instructive text for living our lives. I didn't want to hide the quality that the footage comes to me in, some of it’s lower res than others, I'm not precious at all about quality, because I want everyone to feel like they have a right to access this material and really sift through it.

Nels Bangerter is an incredible editor, he did all those effects himself, actually. We wanted it to feel like the process of clawing your way. What's the closest we can get to these pixels, the halftone? We're seeing the screen in front of us and you both feel a distance in that way, but also getting as close as possible.

SP: I think that's what people want. I think that's what people go to films for, to feel engaged in something and to write themselves into what they're watching or see what they can pull out for themselves. That's what I do as a filmgoer. And the things that really resonate with me are ones where you're making sense of something as you're watching it. I think that's regardless of any kind of film. If it works, that it challenges you or resides someplace in your psyche and you carry some part of it with you forward. So it’s not an activism film in that I have a specific goal in mind. It is a film that is born from the frustration of watching, among other things, the same argument for abolition, the same argument for defunding the police, which is so far overdue, happen in such bad faith again. This film really is as methodical as possible, full of citation and data. It's really frustrating to be living in a carceral state that is determined to gaslight its population over and over again, pretending that with law and order there are no new solutions. This film should be a hearty argument against just pouring more money into police training, hoping that maybe it will turn out different this time.

One element of the film is the way the military and the police sort of fuel one another in a weird kind of feedback loop. I think that's something that we can see globally.

SP: There was a consultant on this film, a brilliant historian named Stuart Schrader, who wrote a book called Badges Without Borders. That was published late intot the Riotsville process bu he also covered Riotsville and we connected and he came on the film. His book is about tracing the origins of the police in the US, or its sort of maturation, really, to the imperialist interventions that the US government was taking at the same time and seeing that they're very, very closely interlinked. Lessons that were learned from riot control abroad really informed, were a major part actually, even in the Kerner Commission, of what they call the professionalisation of the police. On a broader level and outside the US, I think, watching the Riotsville footage, the first thing that was so chilling to me is that it’s watching a government declare war on its own people. I think that’s what the police feel like in many communities, particularly Black communities, in the US, that it’s a war against them. I think Riotsville is a visual illustration of that.

Can you tell me a bit about the collaboration that’s going on. There’s the music, the editing and the voiceover, which provides context and a discursive element to the film. How to you work to combine these elements?

|

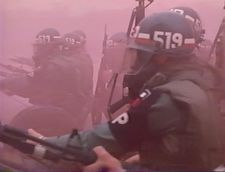

| U.S. civil disturbance training (1967), as seen in Riotsville, USA Photo: Courtesy of The National Archives and Records Administration/Dogwoof |

Jace Clayton is someone I had been speaking to since the very beginning 2015. We just kept in touch as it took a long time for research purposes, but also to get enough money together to actually be able to make the thing. The kind of music he was making changed throughout those years and he would send me things and keep me up to date and by the time we were really digging into the edit he was, like, “All I'm doing now is working with these modular synthesizers. It's an analog technology. There's no stems, you can't repeat it. It's almost like scoring live.” And I thought that was such a thrilling idea - very alive. I only found out towards the end of the project that these modular synthesizers were initially developed, I think, via the US military, and they’re contemporaneous to the time period. So there's an other worldly sound, there's something that bridges the past and present to me in this sonic landscape.

We were all living through a “Trumpian” moment while the film was made. How to you feel about the country now, I a couple of years on from that?

SP: I started this film in the Obama administration and I finished it in the Biden administration. So Trump happened in the middle there. I feel like there's a line that's really stuck with me from the Kerner Commission, that's the vast unfinished business of this nation, which is slavery, has never been reckoned with. I do find hope. The uprisings and 2020 were a really massive mobilisation in most communities, which is really inspiring and hopeful. That they were quickly absorbed into a sort of mainstream narrative of police reform and that they were, merely protests rather than uprisings is troubling and also predictable. But I find that and a broader movement towards labour organising seems to be making a slight resurgence now in the US. So there's a lot of reasons for hope. I do think it just continues to come down to this unfinished business as a nation, you know, reparations, we're not paying.

Now Riotsville is on release, what are you up to now?

I am just starting something so it's hard to know exactly what it is but it’s something about the way that American capitalism operated at the end of the Cold War.. and some sailors.

While we wait for that intriguing next chapter, Riotsville, USA, will be in cinemas from this Friday and available to stream online. For a list of venues and times or to watch at home, visit Dogwoof.