|

| Amanda Seyfried in Seven Veils |

A resident of Toronto himself, Atom Egoyan has a longstanding relationship with the Toronto International Film Festival. It’s really the only place fitting for the première of his latest work, Seven Veils, a project which has been with him, in one form or another, for almost 30 years. A complex, multi-layered work, it stars Amanda Seyfried as the director of a production of Richard Strauss’ operatic take on Salome – more specifically, a restaging of a work by an esteemed director and her former lover, Charles, whose shadow hangs heavily over it, as does the fact that Charles drew on her own troubled past for inspiration. Further complications emerge from interactions between cast and crew members, most notably Johann (Michael Kupfer-Radecky), the exploitative leading man, and Clea (Rebecca Liddiard), the young woman from the props department charged with making a version of his head.

Parts of this draw on Atom’s own experience of directing Salome for the Canadian Opera Company back in 1996, and that’s what he and I began by discussing when we met, just before the festival.

|

| Atom Egoyan |

“The artistic director of the Canadian Opera Company at the time had seen Exotica and felt that the themes of that film somehow related to Oscar Wilde’s play, which had been transformed into this remarkable opera by Ricard Strauss,” he explains. “I have to admit that I didn't see the connection immediately. I was so taken with the opportunity. Having come from theatre, working on theatre at this scale in an opera house was just irresistible. But as soon as I began to look into the material, I went, ‘Oh, yes, he's right.’

“It is a story of frustrated desire and violence. There were a lot of things that were super close to me, but they were shrouded in this very extraordinarily rich use of language that Wilde was presenting almost as a counterfoil to lack of access. You know, when Salome can't have access to John the Baptist, she begins to explain her attraction and the things that she finds irresistible about him, and uses this extraordinary poetic text. It's very difficult to stage as a play but it makes for a really great libretto, and the music is able to then add another layer.

“I was really entranced by it. It's such a powerful piece of music drama. And it's a clear narrative. There's no complexity: it's really a direct line to this inconceivable act of violence, where she actually has John the Baptist beheaded so that she can finally kiss his lips. So yes, this offer was made between two my films Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter which take, I would say, a more discreet approach to issues of abuse and the legacy of abuse. With this offer I could just go full throttle. But then I was left with the legacy of it, because it was a very provocative production. It was very extreme.

“You can't present a production like that now without all sorts of trigger warnings and that sort of thing. There are scenes that will upset you. So when it was being remounted over 30 years later, I had lots of issues about what it meant to be bringing something like that back from another period. And then I began to think of dealing with those issues through this script, through this character, Jeanine, played by Amanda Seyfried. In the story of the film, she has inspired this original production, and she's now in a position where she's remounting it. So she's now bringing back all those stories from her own childhood and seeing them put on stage. And she sets a very high bar for herself, because she's trying to do justice to the original production, but also do justice to her own memory and her own experience. It’s multi-layered. There’s a lot of stuff going on.”

There is indeed. Was that something which he personally identified with because of his own experience on the 1996 production?

“Yes. I mean, I did have questions. I felt that that production was presenting something which hadn't been seen in Salome, which was using the dance of the seven veils, eight minutes of music, as a flashback sequence. Now I've seen other productions that do that, but it was doing something quite innovative at the time. It was also going really far in trying to understand why she would resort to such a unbelievably violent act – that this wasn't coming out of nowhere, that there was something in Salome’s background that had made her aware of what it meant to experience violence against the body, and that she'd experienced it herself. And now she was using that vocabulary in terms of what her actions were.

“She wasn't just a petulant princess, which seemed so outdated. And we didn't have to watch a singer do a dance for eight minutes. It was really about something deeper. But I could understand why it was a bit extreme for people. It needed to have some contextualisation since society has changed in 30 years, of course. I felt that this was the issue that Jeanine was wrestling with. Through this character were things that I was wrestling with, in terms of my own role as a director.”

|

| Erika Sunnegårdh in the Canadian Opera Company's production of Salome |

I tell him that find Jeanine a fascinating character, because she is the director, but she doesn't seem to have much power within the story. There's a lot of power play going on, and the balance of power moves around between other characters, but she seems to be outside of all that.

“Well, I think that the administration of the opera, they're following this curious wish that was in the will of the original director. He had said that if this production is ever remounted she should be the remounting director. I think the administration of the opera believes that she'll just seize this opportunity and not really do anything else with it – which is what you normally do. You don't have time to really change things – or the budget. But once she's there, and she's in that environment, she begins to seek an opportunity to reinvent and to reclaim things that she felt had not been addressed or needed to be addressed in a different way.

“But then she's dealing with the schedule, and she's dealing with the agenda of the administration. And that gets further complicated by the fact that the woman who runs the opera company is the widow of the director who has passed away, so she has her own agenda, and certainly might have known that her husband was having an affair with Jeanine, and so she's also trying to assert her own control over this.

“So there are lots of other things going on around Jeanine that she comes to understand, and a lot of people who are there to purportedly protect her, but no one's really actually protecting her. She's actually very vulnerable. The only person that really is caring for her is the viewer of the film, perhaps. There's an understudy who has a crush on her, but even that is filtered through his Infatuation. He’s probably not really seeing her right. So she's in a very isolated position. I think what's unusual is that the viewer at all times understands and feels her vulnerability, and is with her on this journey.”

I tell him that I find that interesting, because there's an amazing opening shot where it seems that we are, as the viewers, standing in the same position on the rehearsal bridge that Charles loved to be in. And then we see giant eyes on a screen behind the stage watching what's happening. Obviously, a lot of the story of Salome is about watching and viewing, but this seems to, first of all, involve the viewer at that level, and then also give the impression that Charles is still there and still watching, or at least that people feel as though he is.

“That’s really beautiful. I can't I can't say that any better - that's it exactly,” he says, as I blush. “I'm very happy about that. I think the spirit of Charles is filtering through this, but refracted through a number of different people who remember him in different ways. And she's trying to also calibrate that. It's not a clear memory, not just her memory of him. It's also what other people are expressing in terms of their very different relationships with him.”

So how did he approach developing Charles as a character when he's not there, so that we feel his presence as strongly as we do?

|

| Olive Fremstad playing Salome in 1907 |

“There were scenes where we did see him,” he reveals. “We never saw them, thankfully. But there was a whole conversation that she remembered having with him, where she talked about her past, and we saw him absorbing it and generating this idea of collaborating on this together. That didn't make it into final draft, and I think it's more powerful that we have to imagine him, but he did exist as a real character.

“I think Amanda read that early draft. I'm not sure now. There was a conversation that she had with Charles, the conversation where the story was handed over. We never go so far as casting it, but there was an actor in mind, and there's a certain type of director that I can identify. He was larger than life and very charismatic and kind of a problematic character.”

Right from the start, in the theatrical production, there's a lot of layering of projection and shadow and so on. Was that important in its metaphorical aspect as well, because there’s so much layering in the film?

“Yeah, I think so,” he says. “That second shot, where we're seeing in her in her shadow, watching the projection. Jeanine’s shadow, and we have this clear projection of this other avatar of her, the girl. So this idea that the shadows are allowing us access to actions that would be unimaginable to see in real life. So there's a slight abstraction level of obstruction, but also distortion. Shadows are very easy to distort. So there’s the notion of scale, and how she's directing the shadows. The shadow is one dimensional, but it's obviously created, and the result of many other dimensional aspects in front of it that are placed and ordered to create these effects. So there are veils – there's the veil of projected reality, projected image, and then the shadow on that image. It's another way of using light.”

We talk further about the focus on the act of watching within the film. A lot of its concerned with men watching and objectifying women, but then obviously, Salome is watching John the Baptist, and Clea is watching Johann when she’s sculpting his head, which latter is perhaps wilfully misinterpreted. He’s hesitant to go into this too much, however, saying that he still hasn’t had time to sort out his thoughts. It’s all there on the screen and he wants to see how critics like me interpret it.

“I think it's one of the more complex issues that ripple through the film, on a number of levels. And the way, that what's happening with that character is interpreted by men, I think is really telling, and how he doesn't allow her to experience that without interpreting it as vanity. I think that that's clear in that scene, and that becomes really ugly and violent, so it's a whole other conversation. But I think you're right. That's at the core of what the film is all about. And also the consequences of objectifying that, and the different sensibilities that go into that. But the making of the head and Clea saying that her processes is less invasive, I think that's a very strong statement.

“I've been really profoundly moved by the works of writers like Natalie Haynes and Madeline Miller, on how these myths have filtered into the present day. And they talk about other Greek mythological characters, like Jocasta or Pandora, in their written essays on that, but I think Salome is missed, I think Salome is really such an important character. Because it's an extraordinarily violent action that she asks for, but it's ultimately been interpreted by men.

“There's a whole chain here, from the original Bible story to the 19th Century – the plethora of artists who are passing by Salome, from Flaubert to to Gustave Moreau to Oscar Wilde, to Richard Strauss, writing the opera, to Charles doing this production, to me doing this film. I mean, it's all been a chain of men interpreting this imagined female action of violence against a man.”

Something else which interests me about the film, again, related to the subject of watching, i say, is the way that the audience for the opera comes to feel secondary, because the actual creation of the art and the process of understanding that comes out of that is all about the people who are working on it.

|

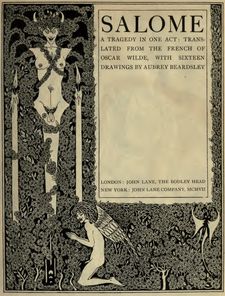

| The frontispiece for Oscar Wilde's Salome |

“Interpreting it was hugely important to Jeanine because of this decision she makes very late not to actually acknowledge the audience,” he says. “Whether or not she's correct in saying that they're still applauding for Charles, ultimately, she's come to a place where their approval is not really important to her. The spectacle of opera and what the singers are generating with music is so public, and yet this is her own very private journey. The last thing she would she want is to have that in any way tarnished by any other energy, other than what she's feeling in terms of her own mission being accomplished.

“I think these works have their own life. When you direct them, and especially in a production like this, you feel it's a very personal work, but that opera will never be really personal because it's a collective public experience. Opera was designed as a civic event so it doesn't allow much room for personal, intimate narrative. So that's trying to weave through this.”

I note that the whole film seems to be a fascinating project for him to take on because it brings together so many of his interests. How did he approach putting all those things together to create a form which felt right and was true to all of them?

“I've been working on this for for a long time,” he says. “I mean, there’s a scene where she's watching on her computer material that I shot with my own little cameras in various incarnations of this over the years. I just felt there was more to explore. I did an early installation where I used imagery from the first production in ‘96. The image of her kissing the head and was used in a projected single channel piece. I have always been drawn to that action. It's a male generated action, and yet it's ascribed to this woman who remains absolutely mysterious and unknown to us and has just been the object of these different interpretations, and elaborations.

“I really felt that this was a way of creating the character of Jeanine, and dealing with all these different male interpretations, right down to the flipbook that he's made of one of his productions. She's having to organise all that. And then by so doing, she's also organising a lot of different aspirations I've had as well, over the years. I mean, she's such a singular character, but are there things that she's doing that are really close to things that I do. And there are moments of despair and frustration that I completely understand, like, where someone is just not getting the direction and you feel something so clearly, and you know what you what you would like it to be, but it's just not going to be that unless you are able to inspire that person.

“Actually, make no mistake, when you're doing that in film it's one thing. You have to do it once and then it's fixed. But when you're doing in theatre, I mean, that's why directors don't often go back to see the show, because the way it kind of evolves over time might stray so far from what they had in mind. But that's because of the nature of theatre. It becomes the actors’ medium. It's not a director's medium.”

We discuss his process in directing someone playing a director – and director partially modelled on himself, at that.

“There are moments when I was directing the opera where I had my assistant director, I gave her my cell phone and I said ‘Okay, can you just can you tape this, what I'm about to do?’ She looked at me curiously. Because I realised that what I was about to do was what I was asking Amanda to do, where there was a singer that wasn't getting something. I was aware that this is exactly what she was doing. You know, where I'm trying to make someone understand what it would feel like to hear a human being produce a sound that's not directed at them, and for them to want that to be sung to them.

|

| Gustave Moreau's interpretation of Salome |

“That moment in the film where she's trying to get the singer to omit that sound and trying to get the other singer to know that frustration is not so far off from what I had been doing a couple of weeks before. I don't think she was duplicating what I was doing by any means. I think she was also just aware – I mean, she's done music theatre, so she understands. But opera is different from a musical, right? Because it's very raw. There's nothing amplified about it. It’s very physical.”

He has another opera project lined up now, he says, which he’s very excited about, but he’s not sure what he will be doing next with film.

“This has been a dream project, and I'm really feeling that I want to take a pause and look at what this what this project means now that it's finished and done. See how it enters the world – a very strange world. I mean, it's going to be odd not to have Amanda here for the première this weekend, but I understand, it's just the nature of it. And then maybe there's something to be drawn from that as well. Where the character doesn't appear on stage for the première of her opera, and then the actor playing it is not going to be here for the première of her film. So maybe there's a poetry there.”