Argentinian comedy Puan follows the life of a college philosophy professor in the wake of the sudden death of his mentor. Marcelo Pena (Marcelo Subiotto in a role specifically written for him by co-writer/directors María Alché, Benjamín Naishtat) finds himself suddenly vying for the position of department head with an ex-classmate, Rafael Sujarchuk (Leonardo Sbaraglia) fresh back from Germany with show-off streak - not to mention a film star girlfriend - at the same time as trying to navigate life in general. The film employs both physical and philosophical comedy to good effect, including iris shots, which close in on Marcello's face at the end of several scenes. Puan took both the Silver Shell for script and for Acting at San Sebastian and we caught up with the filmmakers to chat about the film, which strikes a lighter note than their recent individual work, Alché's drama A Family Submerged and Naishtat's thriller Rojo.

How was it to work on the project together?

María Alché: Yes, exactly, it was the combination of elements, the idea of working with Marcelo, the idea of working together in a comedy, that was something that we didn't do. We've never tried to do this and it was like a challenge, how we will manage to combine the comedy with this set up in this university that is particular. And those were the main elements that drove us to write the script.

I wondered where you came up with the idea that he was going to be flipped upside down. And whether you're a bit worried about going to an actor and saying, ‘Firstly, we want you to stand on your head, and then later we'd like you to sing, is that okay?’

BN: Again, this has to do with the choice of working with Marcelo who is an actor who has a history - he has been a clown, he has been a physical stage actor, so he can do whatever you ask him to do. He is also a musician. He's also a philosopher, because he studies philosophy in Puan in his free time. When you have all these ingredients, you end up with a role like Marcelo Pena.

MA: We want to embrace something of life with the film and we like in the meetings, when people start to sing, or start to laugh or even start to dance. I enjoy it when, in life, suddenly someone does something unexpected.

This is a philosophical film, which is wordy in a way. But there's a lot of silent comedy in it as well and the iris shots are obviously a nod towards silent film. I'm just interested in that tension you've created between the physical comedy and the more wordy stuff

BN: Yes, as you say there was a lot of text in the movie. So the tone of comedy, the iris and very plain cinematic language are there to help the audience go smoothly through the journey you know, it is not a formal film of ideas of mise en scene, it's simple. We came to that conclusion by working together very tightly with Hélène Louvart, who is our fantastic cinematographer, who we admire so much and she put so much into the project. Together we put up this balance to have this film in which you have philosophy and physical comedy.

Is it right that you did the iris shots with a physical camera? Was that a challenge? I’m guessing it was harder to do than it might have been in post production.

MA: Yes, It’s so different doing it in an analogue way.

BN: You have to feel it. You're there with this thing and you have to close it. Feeling the right timing.

MA:It’s so nice to plan a shot with it..

BN: It's nice because you feel connected, like a Chaplin movie.

I also love the scene that’s at an elderly woman’s birthday party. The shot choices are very interesting, focusing on details. Marcelo has said that you do quite a lot of improvisation in that scene.

|

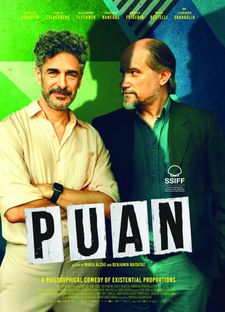

| Leonardo Sbaraglia and Marcelo Subioto on the Puan poster Photo: @TheFabelAgency |

BN: The tone, I think, we found in the editing.

MA: Yes, thanks to Lívia Serpa our editor. She was really working a lot in the party to get the best bite of it.

There's quite a bit of commentary about the idea of Argentinians going to Europe. The idea that when they go back home they feel a nostalgia for the chaos of the country.

BN: It's very linked to the Argentinian idiosyncrasy because Buenos Aires, particularly, is a port city, and historically has been the place of people leaving for Europe but it also has been a port of immigration. So Buenos Aires society is a descendant of immigration, so there is this feeling of the outside as a force that is always present in conversation in aspiration in the fantasy of a prototypical Argentinian. So it's a great element for comedy to have this character arriving from Europe, with his airs and everything. It happens every day in every field that somebody arrives and he's all he has been working in, say, France or whatever. It's part of our culture.

Leonardo Sbaraglia, who plays Rafael, is perhaps better known to an internationalaudience, from films including Wild Tales and Red Lights, than Marcelo because Marcelo is perhaps more usually in supporting roles. When you approached him for the role, was he surprised to be in support.

BN: When he read the script, he said, “I want to do Marcelo.” And we told him, “No chance, Marcelo is for Marcelo.

MA:But Leo is a really good actor and he accepted the role. He was really happy to be in the movie and he's so generous in his working. He immediately asked for a philosophy class. He learned piano and German. He was concerned about all the aspects of his character in a very serious way.

I’d have thought making a comedy can be quite challenging. There’s movement and a dynamic you have to strike

BN: The thing with comedy is that people have to laugh. If there's no laughter when there’s supposed to be you’ve got a big problem. With other genres, let's say a thriller, suspense is a much more subjective thing. But you do remember if you laugh or not in a comedy so, it's greater risk, I would say.

Did it help to be working together so that you could critique it as you go and find the tone between you?

BN: Yes, it's better for writing to change ideas all the time and harder to shoot because we have a lot of arguments and discussion. I want this, she wants that but in the end, here we are and we like the film. I think it's better because we worked on it together, putting our two brains into the thing, our hearts, our souls and, and we're happy to have created something together.