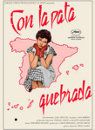

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Barefoot And In The Kitchen (2013) Film Review

Barefoot And In The Kitchen

Reviewed by: Rebecca Naughten

In this lighthearted but occasionally depressing documentary, Diego Galán (former director of the San Sebastián Film Festival) presents images of women as propagated by Spanish cinema. His contention is that popular cinema implicitly reveals something of contemporaneous social circumstances, whether it intends to or not, and that therefore Spain's tumultuous 20th-century and the concurrent prevailing attitudes towards women are reflected in its cinema and female characters.

So the onscreen woman seen most often during Spain's Second Republic (1931-1939) was happy-go-lucky and fun-loving, and although melodramas asserted the more traditional values espoused by the Catholic Church (in one clip a priest declares Woman to be more dangerous than typhus or cholera, and capable of outdoing the Devil himself, which would be quite impressive if true), the sexual freedoms of the time were also present, illustrated here by flirty song and dance numbers and naked ladies being playfully whipped by lion tamers. But that came to an end with Franco's dictatorship: women (and men) lost the right to vote, divorce was suppressed and abortion made illegal, and women were 'liberated' from the world of work (where they had previously held equal rights) and told to stay at home. The next 40 years offered few options for Spanish women onscreen or off.

During the dictatorship, there was no happy ending for Spanish women on the big screen unless it ended at the altar (and further down the line, motherhood). Double standards were in operation with adultery a one-sided 'sin', and men allowed to revel in bachelorhood and comically avoid marriage onscreen while Galán finds multiple examples of their female equivalents being portrayed as ugly, fat, old, and possibly mad. Although a few films (for example, Main Street (Calle mayor) (1956) and Aunt Tula (La tía Tula) (1964) suggested that religious and social oppression blighted women's lives, the single woman was generally denigrated onscreen as she conflicted with the regime's ideal of womanhood. Besides marriage, the only other acceptable option was to become a nun. Those films often featured women with a wild past (cue: Sara Montiel sashaying across a dance floor wearing little more than some strategically-placed feathers) who subsequently resign themselves to a self-sacrificing existence (cue: Montiel in a nun's garb, complete with false eyelashes).

Even in the early Seventies, as foreign tourists started to flock to Spain, the double standard was maintained, with Spanish men portrayed leering at (and getting their leg-over with) bikini-clad foreigners, while Spanish women had to remain 'decent' (no bikinis for señoras or señoritas): Concha Velasco's eponymous character in Susana (1969) wryly observes that "the tourists arrive, put on their bikinis, and the indigenous population rejects the local produce". After Franco's death things started to change, but as Galán traces issues such as domestic violence, abortion, divorce, and women in the workplace as represented in films from the 1970s onward, he emphasises that Spanish women had problems long after democracy was regained - misogynistic attitudes were deeply ingrained in Spanish culture and difficult to overthrow.

A documentary like this highlights the paucity of Spanish titles available in the UK, as few of the films included have screened here. Galán utilises images from almost 180 films and although his film is intended as a history of the status of Spanish women as reflected onscreen, rather than a history of Spanish cinema, it is noticeable that he enlists some obscure films to his cause.

Does that undermine his argument about popular cinema, or simply indicate how widespread the attitudes portrayed were? It's difficult to say because little context is given for the films themselves (were some of them commercial hits that have since faded into obscurity, or did they sink without a trace at the time?). But including better-known films, or more of those that actively engage with the issues he raises (or that surreptitiously went against the grain), may have strengthened the narrative he constructs.

Overall, Barefoot And In The Kitchen is worth seeing to remind ourselves how far Spanish women have come (and what they risk losing once more in Spain's current political climate).

Reviewed on: 10 Mar 2014