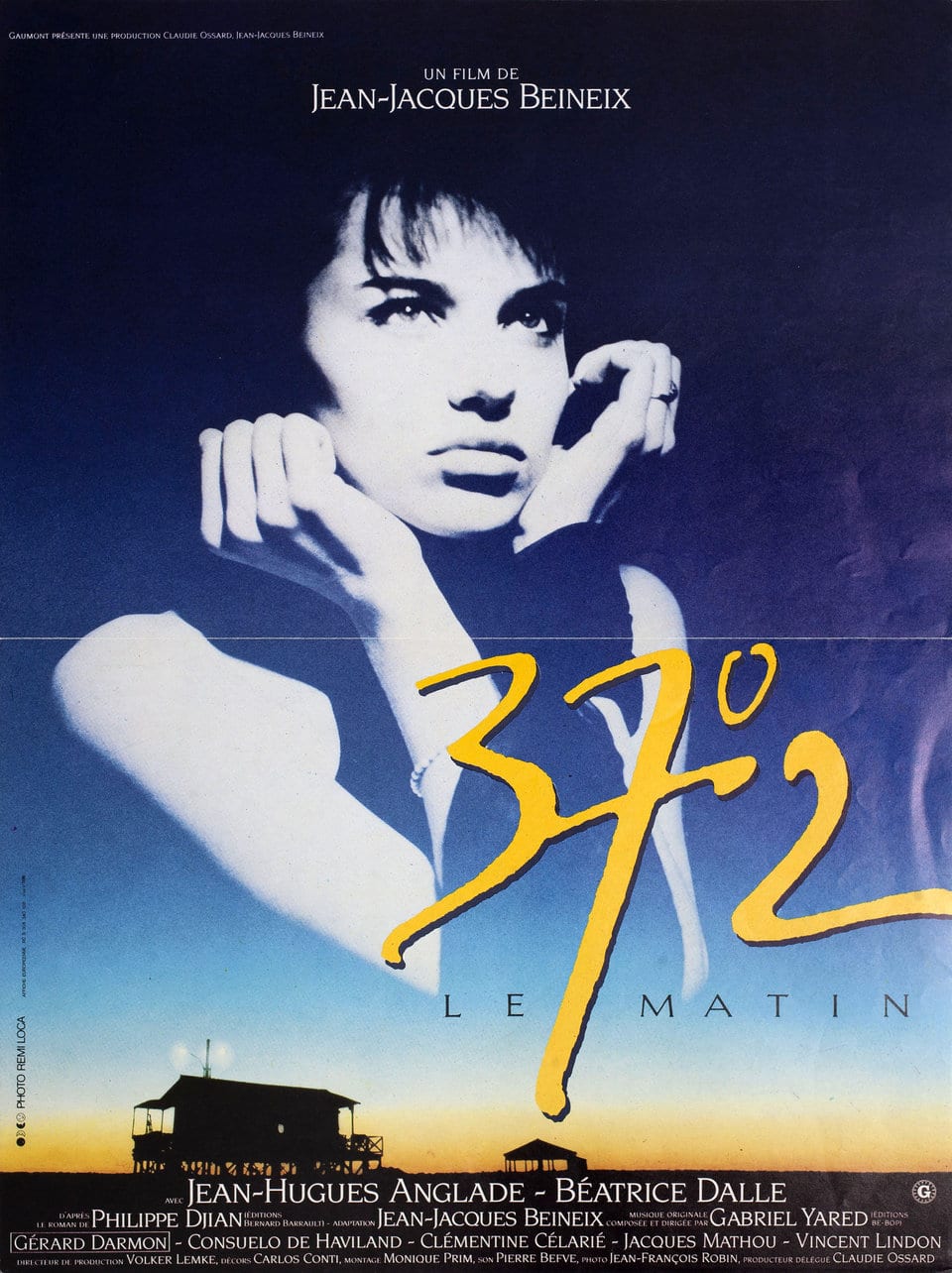

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Betty Blue (1986) Film Review

Betty Blue

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

The bastard child of the French new wave and Eighties post-punk sensibilities, Betty Blue is a love story whose narrative is almost incidental as it appeals directly to the senses. It's the story of handyman and would-be author Zorg (Jean-Hugues Anglade) and his tempestuous relationship with Betty (Béatrice Dalle), a woman who experiences the world with an immediacy and passion that gradually spills over into madness. As Betty's violent outbursts grow more frequent and her connection to the world more fragile, she carries Zorg with her on a journey outside the framework of ordinary life, becoming his muse and threatening his destruction.

Filmmakers and audiences alike inexorably gravitate toward tales of romantic obsession, yet it's rare to see one depicted with the same spirit its heroine embodies. Betty Blue is a film that hurls itself into being, brash and unbridled and now. It has its long, slow, dreamy moments, yet these two are more poetry than prose; there seems to be nothing here that is calculated or rationalised, so the story feels very natural despite its extremes.

Anglade is excellent in the challenging role of Zorg, balancing an everyman sensibility with a passion of his own that makes his attachment to Betty - and his return after their various fights - believable. Dalle, meanwhile, gives the performance of a lifetime, creating a heroine by turns as frightening as she is charming, as sexual as she is vulnerable. For all its artistry it's an unusually accurate depiction of mental illness, with dark hints at the external factors that may have contributed to its development. Betty's relationship with her illness is like Zorg's relationship with her; it exhausts her, imperils her, and yet it is a vital part of her. This is a rare portrayal of insanity that doesn't detract from its sufferer's humanity.

The original French title of this film hints at the oft-mentioned heat in the film - full of sweltering imagery thanks to Jean-François Robin's vivid cinematography - and it also references the body temperature of a pregnant woman. Pregnancy becomes an issue late in the film, but throughout there is the sense of something growing, something brooding, within the story and within its characters - Zorg's gestation of his novels, Betty's scarce ability to contain the energies within her. Bouts of frenzied sex (this is one of those films that briefly caused a scandal as the sex was probably real) seem to provide only temporary relief; what is inside must eventually erupt into the world, and this creates a tension that provides the film with focus even through its more langurous passages, the moments of calm within the storm.

If you're tempted by the director's cut, be warned - the French title for this, 'version longue', means what it says. Over an hour of extra footage significantly shifts the balance of the film, though it manages remarkably well to sustain its atmosphere throughout and there is a delightful sequence in which Anglade disguises himself as a woman to undertake a robbery that's well worth catching. It's also interesting for those approaching the film as art because Jean-Jacques Beineix and Robin plainly had a surfeit of visual ideas - all elegantly realised - that they couldn't fit into the original cut. The sun has never looked so bright, the trees never so green, in any other film - yet as Betty notes, there's something about the colour blue that comes to dominate everything else. Something pure, something uncompromised, like all the greatest works of cinema, like the madness that condemns the film and its heroine to fall just short of what they might have been and yet to become something unforgettable.

Reviewed on: 05 Apr 2012