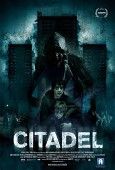

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Citadel (2012) Film Review

There’s been a spate of high rise-set genre flicks recently – from the action beats of Dredd and The Raid to the Carpenter-esque Tower Block, sci-fi comedy Attack The Block and occult horror Outcast – but Citadel stands out as something different and altogether more perturbing, despite the disingenuous ‘hoodie horror’ tag. Anchored by a sincerely anguished turn from talented young Welsh star Aneurin Barnard and imaginative writing and directing from debuting Ciaran Foys – cathartically tapping into his own experiences – the film effectively exploits several commonly held fears, both primal and contemporary. It all unravels a little towards the end as the action grows increasingly derivative of feral child chillers like Ils and Chernobyl Diaries, but it’s an intense and surprisingly heartfelt experience.

After his heavily pregnant wife is left in a coma by an attack from hoodied-up youths, deeply disturbed Tommy sinks into agoraphobia, unable to overcome his guilt for being so helpless to protect her. Reunited with his baby daughter Elsa after months of treatment, Tommy rarely leaves his home, worried in case he should bump into the youths again. When he runs into a gruff priest, his paranoia is amplified by intimations that the hoodies may actually be after Elsa, and may not even be human. A sympathetic nurse offers solace and shelter, but Tommy knows he will have to face his fears if he wants to keep his baby safe long enough to get out of the ghetto.

Wasting no time in getting underway, the pivotal attack is handled with aplomb, the panic Tommy feels conveyed through the use of distancing shots and Barnard’s brilliantly expressive performance. The details of what follows are harrowing in the extreme, and while Tommy’s situation can occasionally sink into melodrama, Foy’s measured pace and the committed performances keep the tension simmering. At times it’s reminiscent of ultragruelling no-budget shocker Combat Shock, with the same perma-wailing baby and sense of ever-present trauma ratcheting up the discomfort.

Foy shows real flair in milking Glasgow’s apocalyptically run-down housing schemes for their ghostly foreboding, the wintry streets and metal-boarded windows often reminiscent of Silent Hill’s otherworldly locale. While much of the duration is actually set within a semi-detached council house – the type recognisable from Shane Meadows’ oeuvre – this in itself becomes a claustrophobic shell, with the flimsy locks and window panes on the door barely separating Tommy and Elsa from the outside world.

When that world comes knocking, it’s truly horrifying stuff: Foy really knows how to spook the audience, with background shapes shifting in and out of focus and vicious lunges from the dark, using the inherent claustrophobic menace of underpasses and buses for later suspense sequences. The terror grows exponentially as it becomes clearer what Tommy faces, even if much of this relies on ludicrous exposition from the ever-reliable James Cosmo.

There’s also solid support from lovely Wunmi Mosaku as a caring nurse, whose tentative romance is played ever so delicately, and the baby used is effortlessly endearing despite the upset the filmmakers must have had to cause her. This is really Barnard’s show though, putting in a wired and emotionally scarred performance that will hopefully propel him onwards and upwards.

There’s perhaps not enough back-story to Tommy and his wife’s situation: we never learn about their jobs, or how they ended up in such a deprived area, although it could be inferred that they’ve been unemployed and housed there by the council. Despite the under-developed class warfare element – some characters express revulsion towards the lower-class while others plead for empathy towards them - the script mostly avoids political brow-beating, using the backdrop of social and economic misery for atmospherics rather than to try to sell an obvious message.

Where such under-rated recent Brit-horrors as Cherry Tree Lane and F alternately humanised its thugs or made them a faceless menace, Citadel eventually takes a more cliched tack. For a while, it ploughs a pleasingly ambiguous furrow into our fear of these delinquents, much like the promising but under-whelming Heartless. There’s an echo of Clive Barker here, calling back to the demonic urban legend of Candyman and its source novella The Forbidden, but ultimately Foy is let down by his need to provide a satisfactory climax.

That he mounts this with undeniable skill saves the film from collapsing into silliness, keeping lighting to a bare minimum and amping up the jolting sound design even further than in the more subtle preceding set-pieces. He also shows courage by ending the film so sharply, with no attempt to leave the viewer pondering anything that’s just happened: this will be refreshingly unpretentious for some viewers but may seem overly abrupt for others.

Overall, Citadel is definitely one of the better British horror films of late, rooted in relatable sentiments and made with considerable care. The acting is well above par for this kind of fare and the cinematography belies the simplistic budget. Not enough home-grown films can claim to be genuinely frightening but in this regard Citadel excels; that it marries its scares with real emotional investment makes it a terrific debut for Foy and an excellent showcase for Barnard.

Reviewed on: 10 Jul 2013