Eye For Film >> Movies >> Commitment To Life (2023) Film Review

Commitment To Life

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

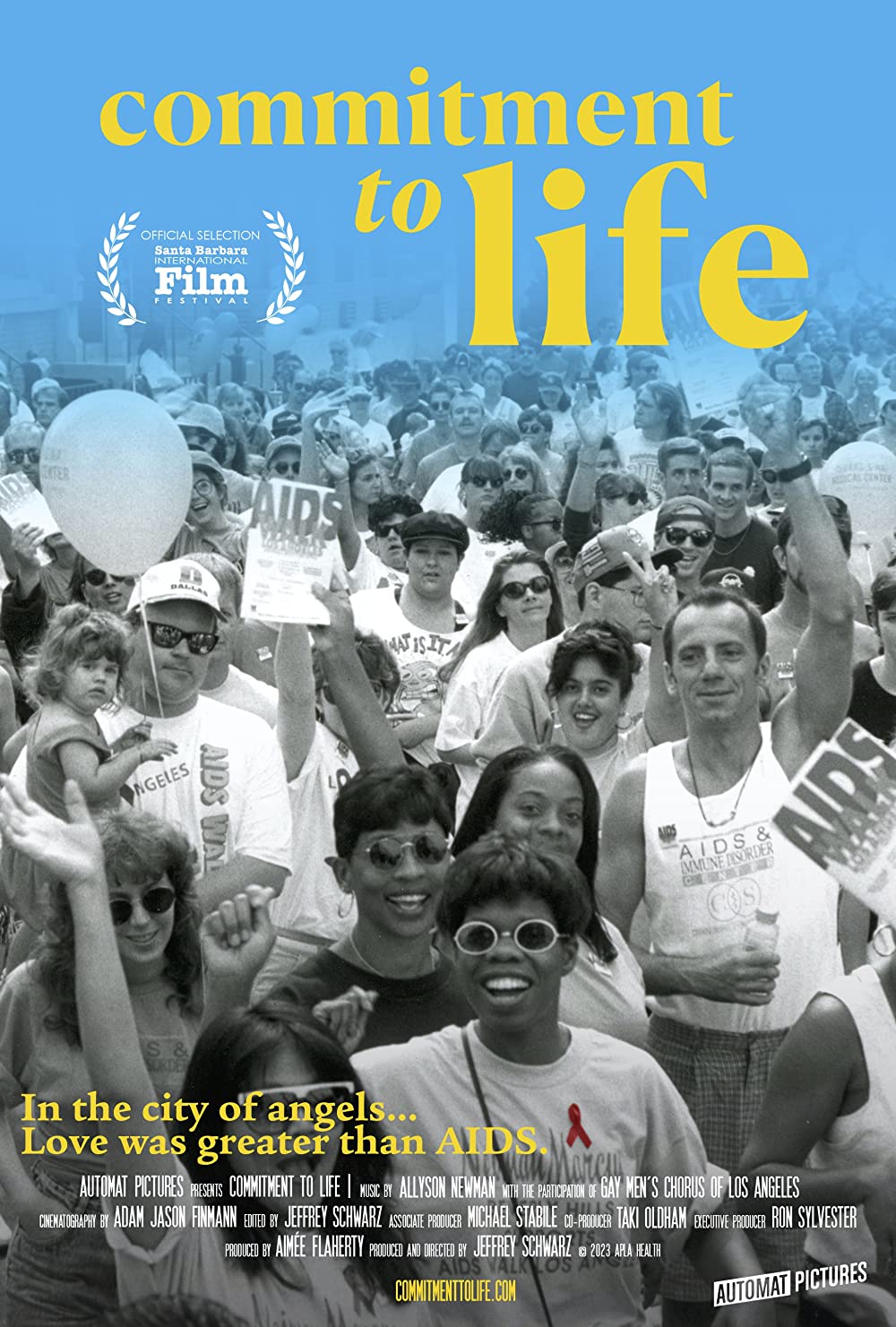

Four decades after the start of the AIDS epidemic, there are still many stories to be told, and at a point in our history when the risk of other epidemics and pandemics is higher than it has ever been, everybody should be paying attention. Where How To Survive A Plague focused on the US East Coast and the work of activists in New York City, this documentary, which screened as part of the 2023 Santa Barbara Film Festival, looks at how the disease emerged on the West Coast, the terror and confusion which it initially caused, and the way that the gay community, its needs largely ignored by wider society, rallied to spread vital information, support the sick and lobby for a cure.

The two areas are, of course, culturally very different. Where New Yorkers turned to legal and academic tradition to develop their own skills and take practical action, Californians looked to their most obvious asset: Hollywood. It was there that the battle for hearts and minds was fought. Now that HIV has come to be thought of as a chronic illness, downplayed to the point where organisations are struggling to get the funds needed to keep people risk-aware and pursue its eradication, viewers may find it difficult to understand the mindset back then, so the film begins by addressing the early history of the outbreak, with some of the few survivors, plus nurses and those who lost loved ones, sharing their stories.

Jeffrey Schwarz, one of the most prolific documentarians working today and a man who has dedicated his life to redressing the balance in regard to LGBTQ+ narratives, is careful not to deliver only those stories which we have all heard before. From the very start of the film, he foregrounds Black voices, and there is a section focused on the different way in which the epidemic affected Black people, who mostly inhabited different social spaces and were missed by some of the early information campaigns, thinking of AIDS as a white gay men’s disease until it was too late. Jewel Thais-Williams, owner of the legendary Catch One nightclub, makes a valuable witness, going on to discuss many additional aspects of what followed. The film also looks at other communities of colour and the social factors which made them particularly vulnerable, as well as the ways in which AIDS affected trans people, who were largely missing from the conversation at the time despite the fact that many fell ill.

There’s also an extensive focus on AIDS Project Los Angeles and the vital work done through its AIDS hotline even before very much was known about the virus. Its work is put into perspective by reflection on the weekly memorial services held for staff, around a third of whom died during its first year of operation. This was in a time when it was difficult to get people with AIDS accepted by hospitals or even, after their deaths, by mortuaries. The systems which activists came up with to provide support are inspirational not just emotionally, but as a practical model for handling crisis situations.

There was also a dark side to it all. “That era was the ugliest part of human beings and how they behave,” remembers Melinda Serano, a dedicated HIV/AIDS nurse. The film looks at Lyndon Larouche’s campaign to quarantine sufferers, which exploited public ignorance for political ends, and Jessie Helms’ condemnation of those affected. A mother remembers how she went to meet him and how, after hearing that she had lost two of her sons to the disease, he refused to touch her.

It all changed with Elizabeth Taylor. Male celebrities had feared being assumed to be gay if they spoke out on AIDS (indeed, it’s telling that that rumour still clings to Tom Cruise, one of the few who did), but she had unparalleled reach, and after being approached to lend her name to an awareness campaign, she became a relentless campaigner herself. The second half od this film focuses primarily on that side of the work. Her presence at the inaugural Commitment To Life benefit dinner would be the first of many. The support of other celebrities like Joan Rivers and Madonna is also celebrated, along with that of David Geffen, who outed himself in public before going on to provide campaigners with a financial lifeline. In an age when celebrity involvement with any kind of campaigning is frequently sneered at, Schwarz does a good job of conveying the risks these people took and what a vital difference it made, with Taylor finally getting President Reagan, who had ignored it for years, to acknowledge that the epidemic was happening.

There are some powerful personal stories woven into this, and the film ends with a reminder that the struggle is not over: a quarter of people living with HIV today can’t access anti-retroviral therapy. Nevertheless, this feels like an appropriate moment to look back at what has been achieved. It’s a reminder not just of the dangers of disease, but of how vulnerable people can become when society chooses to forget about them – and of the role of the arts and culture in fighting back against that.

Reviewed on: 19 Feb 2023