Eye For Film >> Movies >> Death Watch (1980) Film Review

Bertrand Tavernier’s 1980 curio Death Watch remains a chilly and enigmatic film, one which is hard to love but not hard to admire. A French-German production, shot in Scotland with an international cast from America, Austria, Britain, Sweden, France and god-knows-where-else, there is inevitably a stilted, lost-in-translation feel to some of the scenes, particularly those relying heavily on dialogue. However this rather oddly works in the film’s favour, giving this sci-fi tale of a man filming the death of a woman with a terminal illness a disjointed rhythm, which remains part of its charm.

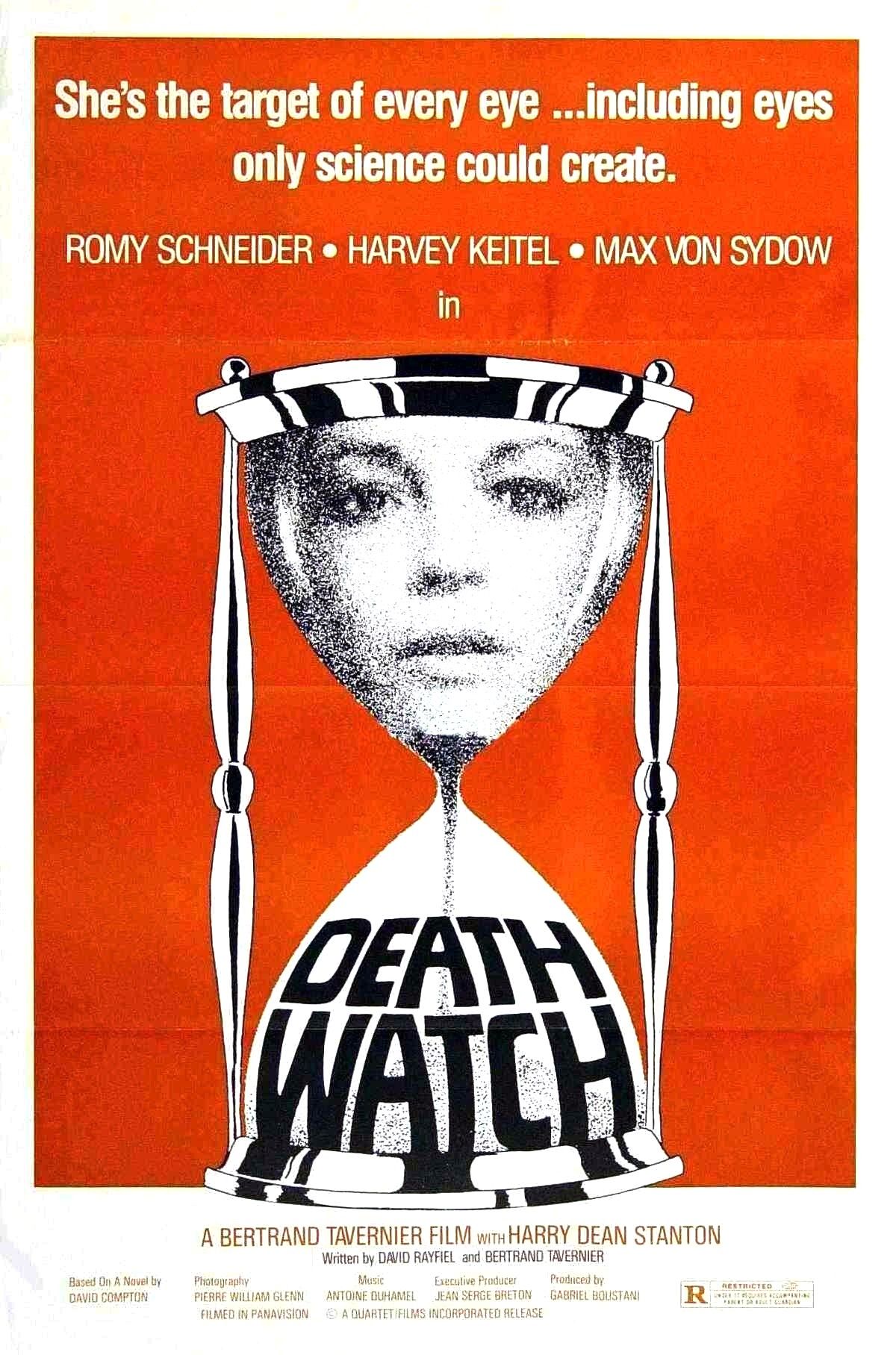

The woman in question is Katherine (Romy Schneider), who has an incurable illness and is given just 2 months to live. Which is rather convenient for TV producer Vincent Ferriman (Harry Dean Stanton). Ferriman is looking for a new protagonist for his show Death Watch, and the slow, suffering demise of Katherine seems to fit the bill. Roddy (Harvey Keitel) will quite literally be Ferriman’s eyes on this job, having had cameras implanted in his peepers for the purpose of documenting the death.

Like the earth-bound sections of Godard’s Alphaville or Tarkovsky’s Solaris, Death Watch works well by not imposing futuristic sci-fi gadgets and gismos in front of the characters. Instead it is grounded in the weirdness of our own time, and the grim drudgery of urban Glasgow is a fitting backdrop to the spectacle. To that end, cinematographer Pierre William Glenn excels in conveying the dread of death in that grey, grim and ever-foreboding sky which looms over the gritty grandeur of Glasgow. All of it captured in hand-held widescreen glory, which again discomforts us. The floating roaming camera-work somehow feels abnormal in comparison to the princely, stately vistas that often accompany such widescreen shooting.

All of this makes it sound like Death Watch is a bit morbid. Well, obviously it is. However, there’s also a jet-black humour at work – when driving a hard bargain over the cost of her participation, Katherine tells Ferriman: “After all, I've only got one life to sell.” Along with the occasional gallows humour, there’s excellent performances to keep the heart engaged as well as the mind. Keitel, in particular, offers just enough ambiguity as to keep us guessing how exactly such a decent-seeming bloke can go along with all of this. And of course, if ever you wanted someone to play a cynical, world-weary TV producer, Harry Dean Stanton would be your first call.

At one point, as Ferriman tries to justify the show’s premise, he says that “death is the new pornography”. Perhaps it’s a stretch, but the film takes aim at our voyeuristic desires – and how easily sated they are by 24-hour television – and that central premise seems to grow in relevance as the decades have passed since its release in 1980. Our desire to watch reality – even when that reality is always filtered and created by unnatural circumstances, much like the making of a movie – unfold through the mirror of a TV screen, rather than living out the extremities of life on our own, is a peculiar phenomenon, and one not easily explained away.

And Death Watch doesn't try to explain it all away. Like Godard’s aforementioned Alphaville, Death Watch is a sketchy romp through a philosophical landscape indebted to the cinema. Tavernier references Budd Boetticher’s classic Western, The Tall T, in a poster on the wall of Ferriman’s office. Like that film, Roddy ends up cooped up with a damsel in distress, mercenary eyes watching his every move.

And of course, the irony is, Roddy has to watch it all too. The camera implants in his eyes mean that he can never sleep and, like any other camera, needs a constant light source to function. So he must follow Katherine around, his eyes wide open seeing nothing and everything all at the same time. Until the inevitable darkness closes in. That’s the thing about car-crash TV, you can’t stop watching until it’s too late.

Reviewed on: 14 Nov 2012