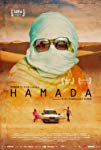

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Hamada (2018) Film Review

Hamada

Reviewed by: Rebecca Naughten

After the death of Franco in 1975, Spain gave up its former colony of Western Sahara and effectively allowed the territory to be taken by Morocco, without giving the region's inhabitants - the Sahrawi people - the right to self-determination. The subsequent 16-year guerrilla battle for independence and its repercussions have received little international attention, despite the sustained involvement of the United Nations. The territorial conflict since 1975 has pushed the Sahrawi into more than 40 years of exile and seen them divided between territories occupied by Morocco, 'liberated areas', and the refugee camps in the Tindouf hamada (over the border in Algeria). The latter is the backdrop for Eloy Domínguez Serén's depiction of the everyday lives of twenty-something Sahrawis.

We are told at the outset of the film that 'hamada' is a geological term referring to a desert terrain that consists of a flat and rocky area mainly devoid of sand. But for the Sahrawi it also means 'emptiness' or 'lifelessness' - an equally accurate description of the barren landscape that offers them nothing but stasis and stifling heat. Days run into nights and nights run into days. Time is whiled away either by seeking work (of which there is little) or hanging out with others in the same position. The Sahrawi are stuck in a state of perpetual waiting.

Despite these desolate circumstances and habitat, Domínguez Serén's film buzzes with humour and human warmth. Although there are - unsurprisingly - moments of melancholy, this is an upbeat celebration of indomitable spirit shown in the face of a frankly depressing situation, and a demonstration that resistance can take many forms. Unexpectedly comedic, the sunny nature of the film is thanks to the three individuals that it takes as its focus: Sidahmed, Zaara, and Taher.

All of a similar age, their personalities are sufficiently distinctive to offer different perspectives on their situation: Sidahmed is diligent, industriously turning his hand to anything mechanical, dreaming of getting to Spain and being able to send money back to his parents; Taher is slipping into the inertia caused by long term unemployment, but still aspiring to meet 'French girls'; and Zaara...well, Zaara is a one-woman powerhouse. With the sunglasses and style of a fashionista - not to mention personality to spare - the diminutive young woman steals the show with her determination to live on her own terms (any man looking to marry her would need to accept that, "Where I say I'm going - that's where I'm going"), to find a job (what she lacks in experience, she makes up for in gift of the gab), and to learn to drive.

Cars - and the driving lessons that Zaara takes with both Sidahmed and Taher - are a through line in the film. They are a symbol of identity (for example, Land Rovers are mentioned by name in folk songs related to the fight for independence) and social status, a frequent topic of conversation, a form of capital, and a source of pride and demonstrable mechanical know-how. A car equals mobility, so therefore cars are freedom.

The spontaneity and naturalness captured on film - they seem genuinely oblivious to the camera's presence - is a testament to the bond that the director has formed with the three. Domínguez Serén has been going to the Tindouf Sahrawi refugee camps since 2014, when he applied to teach at the camp film school. Started with the intention of allowing the community to express their identity and history on camera - and to draw attention to their plight - the director describes making the film as a collaborative process that was guided by what the three protagonists wanted to express about life in the camps. His own experience of being a migrant - detailed in his earlier film No Cow On The Ice - perhaps gives Domínguez Serén additional insight into the experience of being outside your own land, and what that means for your sense of identity and belonging. He films the Sahrawi youth with empathy and sensitivity - they are lucky to have him as their cinematic advocate, and the resulting film is a treat to watch.

Reviewed on: 02 Jul 2019