Eye For Film >> Movies >> Journey To The West (2014) Film Review

Journey To The West

Reviewed by: Rebecca Naughten

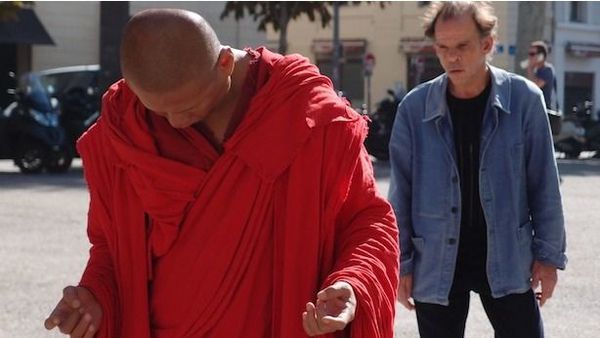

Both a postscript to his (apparently) final film - Stray Dogs - and a continuation of his Walker series, Tsai Ming-liang's Journey To The West is a meditative miniature of hypnotic grace. The recurring figure in the Walker series is a Buddhist monk (played by Tsai's habitual leading man, Lee Kang Sheng) who is here seen moving at a snail-like pace on the coastline and streets of Marseille, and acquiring an acolyte of sorts in the form of Denis Lavant.

The film starts with an extreme close up of Lavant's face, lying on his side with one half of his face wreathed in shadows - his hidden eye gleaming in the dark - the lines and furrows of his face captured in intimate detail, and the beat of his pulse visible on his neck. There is no dialogue in the film but - as thoughts flit across Lavant's face - his silence and the rhythm of his breathing lull us into contemplation. The sound of his breathing is a soundbridge into the next shot, of Lee's red-robed monk, mixing with the wind that blows through the stone structure that the monk is slowly traversing.

There follows a sequence of shots (there are only 14 shots in the film overall) alternating between the monk's progress and close ups of Lavant's face, now lying down outside - the sea and birds of the port audible on the soundtrack - with his profile imitating the craggy coastline upon which the fluttering red robes eventually become visible in the background. The focus then switches to the monk, and the discipline and poise of Lee's movements are contrasted with both the completely stationary (a mannequin) and the hustle and bustle of the crowded city.

The centrepieces of the film are two extended shots which are long enough in duration for the light to perceptibly change. The first lasts more than 15 minutes and sees Lee make his way down a flight of stairs in a public walkway, members of the public either staring, backtracking or walking around him (small children are fascinated by him - one small boy stumbles in his footing so caught up is he in the almost immobile figure). As Lee descends he is backlit with a golden halo effect around his silhouette and a reflected red aura (caused by the red robes) in the gloom, the camera subtly moving to reframe him in his descent - the magical lighting (dust motes visibly dance through the air) makes him appear to almost float down the stairs.

In the second extended shot, Lavant reappears (he is briefly visible in the preceding shot as the monk passes a carousel), following about four steps behind Lee in almost-unison of motion - much to the bemusement of the drinkers outside the bar they pass by. Part performance art, part feat of physical dexterity - the balance required to maintain posture when moving at such an exaggeratedly slow pace is impressive - the two men together form a hypnotic display in which Tsai utilises the whole of the frame.

By the film's final shot - an upside-down reflection in a mirrored canopy of a crowded plaza - you find yourself actively surveying the width and height of the screen, awaiting the flash of red that will signal the monk's arrival into the frame. One of several shots filmed in - or containing - reflection, this final shot challenges our perception and forces us to consider things from a different perspective, effectively causing us to slow our own pace in an echo of the film's contemplative form.

Reviewed on: 09 Nov 2014