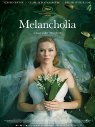

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Melancholia (2011) Film Review

Melancholia

Reviewed by: Chris

What is the one thing of which you are most certain? Certain beyond your wildest dreams, your worst nightmares?

Justine is getting married. A wonderful wedding with the best wedding planner. As she lifts her head to enjoy the kisses of her groom we sense the sparkle of love entering what might be a world of darkness. Kirsten Dunst comes of age as an actress in this finely sculpted character as a successful career woman enjoying a magnificent day in all its finery. No expense has been spared. Yet somehow we can sense, in this beautifully interiorised performance, that the tinsel of the outer world means little to Justine.

The truth is that she suffers from clinical depression. A disease with which our director, Lars von Trier, is also afflicted. Does the film tell us how depressing the world is and ask us to feel sorry for its leading protagonist? Not at all. While von Trier has used his own experience to create a vivid reconstruction that goes beyond sympathy or melodrama, the film is ultimately a celebration of Justine’s strength and inner clarity. Her non-attachment to the trappings of happiness – things in which most people would seem to find great joy – is almost Zen-like in its conviction. Why do we go to such lengths to find meaning in transitory and superficial sense-gratification? Love, the deep and wonderful communication of one person with another, can’t be bought or bartered. Yet we spend our lives building castles of sand – even as expressions of ‘love’ – and if Justine can’t have the real thing in each touch, she certainly doesn’t want to settle for lust dressed up in lace.

Von Trier is becoming increasingly operatic in his films. The theme music from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde provides a perfect setting for this grand vision of life and meaning. The liefmotif reminds us that, beneath everything, there is a more serious theme at work. If death is the only real certainty of life, this is symbolically illustrated in the second half of Melancholia. For someone who is deeply depressed, death is a mere detail. But for others, it is the worst of all possible eventualities. To get the point across in the most vivid way, and also show how Justine’s illness gives her a strength denied ordinary mortals, von Trier turns his film into an end-of-the-world movie. A rogue planet (aptly named Melancholia) hurtles through space and, having narrowly missed the some of the other planets, is on a collision course for earth. As the actual collision has been previewed in the film’s opening scenes, we already know that last minute intervention (for instance, to save the Earth Hollywood-style) is unlikely.

As supporting characters struggle and eventually lose the battle to convince themselves that everything is okay, Justine warmly embraces the development. There are two nude scenes – when one might say that our heroine is not only naked but that her soul is stripped bare. One is when her sister, trying to care for a ‘mentally unbalanced’ Justine, is trying to persuade her to have a bath. The wretchedness of her sorrow is profound: having endured the symbolic show of an overblown wedding reception, she has the lost the one thing that meant something to her. It is in stark contrast to her self-assurance in the second half of the film, where her calmness is like something I have occasionally witnessed in gently smiling hospice patients who know they are about to die. The second instance is more beautiful, although completely unglamorised. As other characters swither between denial, fear and bravado (“Let’s have a glass of wine outside”), Justine calmly enjoys the epiphany. Identifying with the Earth about to meet its nemesis, she bares herself to the onslaught of the coming planet in a gesture that finds her sprawled in adoration on a hillside.

Von Trier’s controversial furore at the film’s Cannes premiere ensured wider distribution than might otherwise be expected for an art-house offering as dark as Buñuel. This perhaps misleads some people into seeing the film with the false expectation of something more mainstream. As one teenager exclaimed, walking out of the multiplex screening I went to, “I’ve never sat through such gash in my whole life.” But to cinephiles more attuned to von Trier’s style of filmmaking, it probably represents his greatest triumph since Dogville. One could even imagine allusions to Justine’s name with the eponymous novel of de Sade, an abused protagonist who accepts approaching death. Raw, original and uncompromising, yet also a work of uplifting beauty, Melancholia is an end-of-the-world movie the likes of which you have never seen before.

Reviewed on: 20 Oct 2011