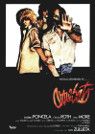

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Rapture (1979) Film Review

Rapture

Reviewed by: Rebecca Naughten

While Iván Zulueta is little-known outside of Spain, the influence of his second (and last) feature film belies the 'cult' label that is often attached to it; Rapture (Arrebato) had far greater reach with subsequent generations of Spanish filmmakers than one might expect for a film denied a proper theatrical release. The film garnered film maudit status after it was turned down by both Berlin and Cannes on the basis of what they saw as its pro-drugs attitude, and a limited release in Spain saw it sink more or less without a trace.

Such is the turnaround of the film's reputation in Spain that when the Spanish film magazine Caimán Cuadernos De Cine surveyed 350 film writers in 2016 - to create a top 100 Spanish films - Rapture occupied 5th place (ahead of it were Viridiana, The Spirit Of The Beehive, The Executioner, and Plácido).

Set in an oppressively humid Madrid in the late-70s, Rapture follows B-movie director José Sirgado (Eusebio Poncela) as his life unravels through a combination of the professional (his second film - a vampire story - seems headed for disaster) and the personal (he is in the grip of heroin addiction and his relationship with actress girlfriend Ana (Cecilia Roth) is mutually destructive). After an aggravating day in the editing room, José arrives home to find that Ana has moved back in to his apartment, and that he has received a package containing audio-visual material created by Pedro (Will More), a young man obsessed with the act of filming (and film watching). Much of Rapture plays out in flashback as Pedro's recording causes José to remember both their first encounter and their second meeting a year ago (when Ana was also present). In the last section of the film, José goes to Pedro’s apartment to try to solve the mystery contained within the recording and accompanying film.

The film’s title refers to a state of being that the central trio – or at least the two men – are seeking. As Pedro explains it, what they are pursuing is that sensation that we have as a child, when we could spend hours focused on one thing and in our own little world. This state relies upon the act of looking (Pedro uses his own Super 8 films as a stimulant), but all three of them also use drugs as their gateway into rapture. The desire to lose yourself in something (or someone) is a common enough impulse, but in Rapture this ecstasy is tinged with horror and the suggestion that both cinema and drugs (the chosen routes into the sublime) are vampiric forces. The film is full of moments of unsettling - and somewhat grubby - beauty alongside a building sense of claustrophobia.

The latter is generated via its limited locations (José’s apartment during the course of the night that he listens to/watches Pedro's recording, the country house where he first meets Pedro, or the bedroom of Pedro’s Madrid apartment), the action frequently taking place in the shadows (faces illuminated by the flickering lights of projectors), and aurally through repetitive elements on the soundtrack (the insistent clicking of the timer on Pedro's camera, and the recurring musical motif of an uneasy lullaby formed out of the sounds of children's toys).

The film achieves a state of grace through the performances and chemistry of the actors. Poncela was the most experienced of the three, and his stillness becomes the calm centre around which the other two chaotically circulate. More was part of Zulueta's social circle and the role of Pedro was written for him. His performance is a compendium of disconcertingly exaggerated vocal tics and gestures - and a breathily insinuating style of delivery on the recording (long stretches of the narrative are conveyed via his voiceover).

But although the film is undoubtedly ‘about’ the men, in her first substantial film role Roth is equally memorable, and she gets an electrifying sequence where Ana dresses as Betty Boop and sings along to the record player. Ana is so vibrantly alive that she jolts the camera into movement – in the only travelling shot of the film, and possessing a dynamism that is otherwise only seen in Pedro’s Super 8 films, the camera follows her as she dances towards José. It is an attempt to win José back, but the siren call of other forms of rapture will persist.

Rapture is a haunting film, both for the way that its inherent strangeness and underlying current of despair get under the viewer's skin but also due to the sense of squandered potential on-screen and off. Zulueta made two further shorts – some ten years after Rapture – but when he died in 2009, aged 66, he had spent years in the wilderness in thrall to heroin addiction and a self-imposed exile in his home city of San Sebastián. He was a unique and exceptional talent, and his disappearance in the aftermath of Rapture's disastrous initial reception was cinema's loss.

Reviewed on: 03 Jun 2019