Eye For Film >> Movies >> Simone: Woman Of The Century (2022) Film Review

Simone: Woman Of The Century

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

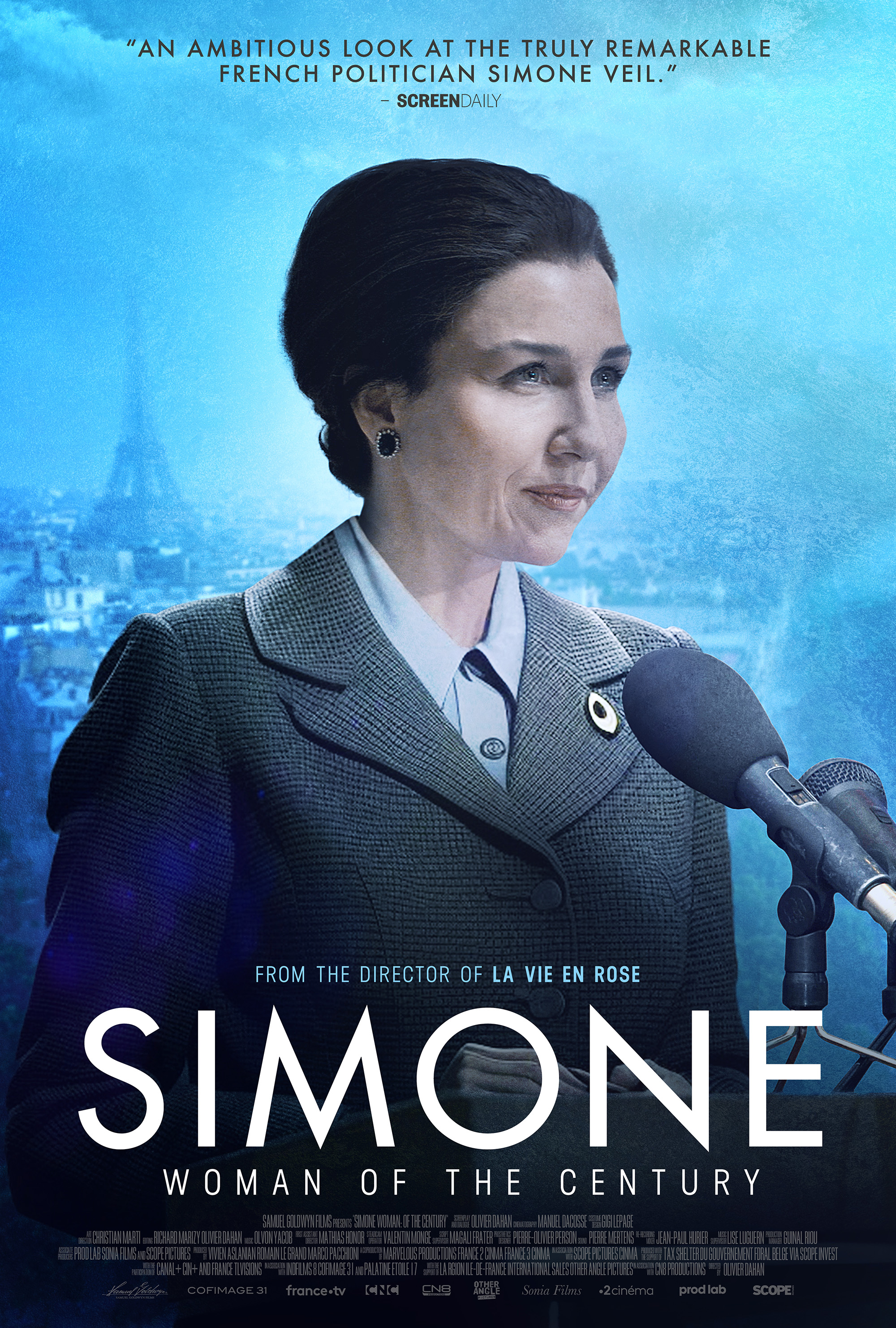

In Bernard-Henri Lévy’s homage to Simone Veil he writes: “The world, French philosopher Gaston Bachelard said a century ago, could be reduced to a series of copyrights. Einstein’s relativity. Descartes’s doubt. Bergson’s laughter. Dante’s hell. Today: Simone Veil’s Europe.” Olivier Dahan’s all-embracing portrait, Simone: Woman of the Century (Simone, Le Voyage Du Siècle), stars Elsa Zylberstein (Claude Lelouch’s Un + Une, L'Amour C'est Mieux Que La Vie, and his upcoming Finalement... Ou La Folie Des Sentiments) as Veil from 1968 till 2006, and Rebecca Marder (Arnaud Desplechin’s Tromperie and François Ozon’s Mon Crime) from 1942 through 1967.

Auschwitz survivor, Health Minister of France, magistrate, mother, member of the Constitutional Council, advocate for the rights of women and prison reform, and the first President of the European Parliament, Simone Veil’s importance for the 20th and 21st century cannot be overstated. Director, writer, editor Dahan (La Vie En Rose with Marion Cotillard as Edith Piaf and Grace de Monaco with Nicole Kidman as Grace Kelly) is no stranger to depicting influential women.

At one point late in the film, Veil’s adult voice asks “How can I define memory?” We see her (Lucie Usal as the 10-year old Simone) happily on family vacation, swimming as a little girl with her mother, Yvonne Jacob (Élodie Bouchez), and her siblings, Milou (Dali Jaspard), Denise (Lilou Kintgen), and Jean (Philéas Vassily), while the father, André Jacob (Bruno Georis), reading on the beach, is looking on. The voice continues: “It stands apart from history through its direct, personal aspect or through a family intermediation with a past event, heavy with consequences. For two or three generations, memory and history are closely bound. This memory is not just contemplative or made up of information. It cannot be totally objective as it constitutes a form of consciousness, a form of identity.”

The visuals change to sheer endless walls, listing the names and dates of the murdered, as her voice continues: “Like it or not, aware of it or not, we are responsible for what will unite us all tomorrow. We are made of what preceded us and that commits us to the future.” Next we see Zylberstein’s Veil looking at this same wall of the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris, where the Jacob names and birthdates are listed in marble. “Memory primarily haunts witnesses, or, rather, the victims, those of us who survived, who experienced the suffering some say is over, but that never truly ends. And will not end until we are no more. Throughout my life, attention to others’ suffering has dictated my behavior on a political level and a personal one.

“Now, when I hear reassessments of the past, that, whatever their legitimacy, trivialize the Shoah as something to put into perspective and consign to the dungeons of History, I truly wonder if our society is not losing its way and confusing all struggles, confusing rights and duties, confusing falsehood and truth, and leading today’s youth along the paths of hatred, racism, anti-Semitism, and xenophobia.”

The camera shows a close-up of the sword Simone Veil was awarded upon being elected to the Académie Française. Engraved are the words UNITED IN DIVERSITY, the motto of the European Union, and the number 78651 she was given at Auschwitz. The voice pronounces a final warning: “There are many false prophets today in France, Europe and the world to lead the weakest among us along those paths. Our task is to thwart them.”

Many outside of France or those too young to have seen Simone Veil speak on television news, will now have a chance to understand some of her immense importance through this remarkable portrayal, initiated by Elsa Zylberstein (also an associate producer). Silence and misinformation can be deadly, a fact Veil, who came from an assimilated Jewish family, knew better than most. This challengingly structured moving picture connects past with present not in linear form but in fragments of story that come in waves. Olivier Dahan has made a film for now and especially for those for whom the binding of memory and history starts to unravel. .

On November 29, 1974 the vote went through to pass the bill to legalize the termination of pregnancy after a live televised debate. As Health Minister she put an end to the criminalization of abortion in France. It is one of her greatest legacies to this day and known as “Loi Veil” or the Veil Act. Dahan includes some of the voices arguing against her. One angry man comments: “If we allow abortion now, homosexual marriage will be next.” The racist and anti-Semitic aggression against Veil leads her in a private moment to ask her husband Antoine (in his later years played by an almost unrecognisable Olivier Gourmet): “Why do they attack me?” To which he responds “because they hate what you represent.” It speaks well for the film that what that what is she represents is not further defined.

Friend Marceline (as an adult played by Sylvie Testud) who experienced and survived several camps and death marches with her is one of the few who understands. When they run into Ginette (Laurence Côte of Jacques Rivette’s La Bande des Quatre), who as a young girl shared the camp experience with them, the social distinctions dissolve right away. Veil’s arguing for social solidarity was never a facade and when the market vendor and the President of the European Parliament are having a coffee, they speak of Auschwitz and how kindness and the gift of a dress can mean everything. “You saved me with a dress,” says Ginette, “it restored my humanity.”

Most powerful are the moments when we hear the words of the older Simone speaking about the end of the war, likening it to Dante’s Inferno, a world with no more rules. All we see is the red fiery sky, followed by a snowy landscape watched from a rolling train, as we listen to the barbarities taking place during Veil’s displacement from camp to camp. She survived Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bergen-Belsen, Dora. Any representation of the Nazi death camps is a precarious endeavor. Dahan and Zylberstein’s goal is clearly to reach young audiences whose knowledge of the Shoah may be limited. Showing the selection at the ramp when the teenage Simone arrives at Auschwitz functions through Rebecca Marder’s perceptive performance, which makes it easy to identify with her - she becomes a guide into necessary awareness.

As a Minister in post-war Paris, a scene in the film shows Simone Veil putting down the first stone for the construction of a new children’s hospital. Complimented about her technique, she simply says, “I used to do this,” and an abyss unexpectedly opens wide into the past. Next, Elsa Zylberstein’s Simone looks into the camera for a photo, a subtle glance that communicates so much about representation. At other times it is clear that information simply has to get out in an efficient way, as when Simone meets Nazi hunter and activist Serge Klarsfeld, (Philippe Lellouche). “Mr. Klarsfeld is here,” we hear announced and in perfectly succinct exposition she tells him who he is, that she is impressed by his work as historian and his “book on the deportation of French Jews.”

Human cruelty did not end with the Second World War and Veil’s work to help those in need knew no borders. A harrowing scene shows a woman (Maryam Touzani’s The Blue Caftan’s Lubna Azabal) speak of the torture she endured in an Algerian prison. Footage from former Yugoslavia in 1992 is commented on by an enraged Veil. She hears the echo of the same arguments repeated: A world waiting for the end of a war while people are massacred and dying in concentration camps.

And yet, as her husband remarks “Building Europe reconciled you with the 20th Century.” The film begins and ends on holiday by the sea during Simone’s idyllic childhood. The image, a serene still-life of a rattan table in the sun, with purple flowers and a lemon, conjures up a quote by Veil’s “phonetic sister,” the philosopher and mystic Simone Weil, who wrote that “Everything beautiful has a mark of eternity.” As a Holocaust survivor who lost almost her entire family by Nazi hands, Veil represented the danger of the truth. “People are scared of other people’s suffering,” she knew, and the fact that she felt the world wanted her to be silent about the horrors she experienced and move on weighed heavily on her.

Reviewed on: 17 Aug 2023