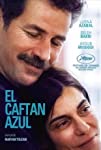

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Blue Caftan (2022) Film Review

The Blue Caftan

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

Maryam Touzani’s handsome The Blue Caftan (Oscar shortlisted from Morocco in the International Feature Film category) begins with the petrol blue cloth that will become the titular garment. A male hand strokes the silk; we see a yellow measuring tape dangling around the man’s neck. His name is Halim (a superb Saleh Bakri), a maalem, a traditional caftan maker who sells his magnificent, hand-embroidered wares in the Medina in his shop which he runs with wife Mina (Lubna Azabal, fiercely intense).

A new apprentice, Youssef (smouldering Ayoub Missioui), seems to be more interested, more eager to learn the craft than the many who came and went before him. It is an old, dying-out profession that produces not simply clothes, but precious objects that take a long time and much expertise to make. We get to witness the process of building one garment throughout and it is mesmerizing to see how gold thread is braided, made into cords with a wooden spindle in the shop’s backyard, and the fingers embroidering delicate loops to form traditional ornaments.

The shop has a legacy, inherited from Halim’s father, and is full of fascinating, worn tools of the trade. Touzani could have let the camera (cinematography by Virginie Surdej) linger even longer on the messy shelves and strands of left-over ribbon. You can almost smell the place, so far is it from the antiseptic quirky production design seen in so many series these days.

“A caftan must be able to survive the one who wears it” says Halim to Youssef, it is to be passed on from mother to daughter and to stand the test of time. Youssef understands that they are in the heirloom production business and the gazes between the two men intensify. Halim is a quiet man, calm, and tender, focused on his work. Bakri’s evocative face with the Walt Disney mustache has a soothing effect on the audience, despite the emotional wounds and inner turmoil Halim experiences.

His wife is the one who mans the front of the shop and deals with customers and sellers of fabric and makers of finely crafted buttons. But something is not right with Mina, she is pale and her main source of nourishment are tangerines which she buys in bulk at the market. One day Halim finds the fruit scattered on the floor in their home. Unlike the Sisi portrayed by Vicky Krieps in Marie Kreutzer’s Corsage (competition on the shortlist for Best International Film), Mina indubitably consumes citrus fruit for other than weight loss purposes.

Halim is worried, Mina refuses to go to the hospital again for more tests and procedures. The petrol blue caftan, a particularly work-intensive, complicated, and expensive piece for a customer, who pushes him to work faster, takes up most of his time. To relax Halim frequents the public baths, also the locus of his secret life. He purchases “black soap” a lard-like substance ladled out on sheets and the physical encounters there are marked by silence and loneliness and stand in stark contrast to the time spent with Mina, when they talk and laugh and play together. Youssef’s entry into the fold isn’t without obstacles. Swathes of presumably stolen pink satin, jealousy, and guilt make it take a while before the three of them can embark on a dance that resembles in some aspects the one in Florian Zeller’s The Son.

Covert glances and dauntless gestures between the three protagonists, that keep us guessing about who knows what, weave a web as diaphanous as the stitching on fine cloth. Love and desire and care and the fractured relationship with traditions come into question. What is possible and what isn’t? So engrossed are we in their lives that only at the end do we fully realize that they live by the water, a fact that throughout the movie only the sound of seagulls was alluding to. That the horizon beyond the winding streets with their shops is wide open over a cemetery by the sea we discover in a supremely touching crescendo.

Fig-shaped buttons on a 50-year old caftan brought into the shop are admired by all. The garment “still as beautiful as on the first day” makes a case in point for customs that need to be preserved and protected. That is not true for all historical conventions, especially those that discriminate, stigmatize, and cause unnecessary suffering. When Halim confesses to his wife that he easily “could have brought shame” on her because of desires he unsuccessfully tried to suppress all his life, she responds: “I don’t know any man as pure as you and as noble.”

Most memorable are the lessons of craft. Never mistake petrol for royal blue! A girl who wants a caftan in dark-rose silk velvet taken in is scolded that “fabric should glide over your skin, not squeeze it.”

Reviewed on: 19 Jan 2023