Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Boy And The Heron (2023) Film Review

The Boy And The Heron

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

Studio Ghibli co-founder, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy And The Heron (a highlight in the Spotlight program of the 61st New York Film Festival and a Donostia Award screening at the 71st San Sebastian Festival, as was Víctor Erice’s Close Your Eyes), his most autobiographical work to date, connects the dots between much of his previous work. From why My Neighbour Totoro resonates so deeply with so many children and adults to why The Wind Rises (2013) had to come before this story of life and death, before and after.

Sirens and wartime and sparks that resemble fireflies start the film. The hero’s mother will die in a hospital in the blaze and the boy Mahito and his father move to the countryside with his stepmother/aunt, the dead mother’s younger sister, pregnant with his sibling to be. This is a lot to come to terms with under any circumstance - think Cinderella - but here in Miyazaki’s most wonderfully magical world, the new abode holds many mysteries. There he encounters seven old servant women, as distinct as Disney’s dwarfs, and a strange gray heron who sometimes speaks and has teeth and who is connected to the magical tower nearby, built by an ancestor, which seems to hold ancient clues about life and death.

The boy eventually encounters armies of pelicans and parakeets that put Hitchcock to shame in a world where up is down and down is up. The difference is, when you are truly trying to rescue someone else and not only yourself, something meaningful, uncynical, and necessary emerges. Mahito questions himself and finds himself unworthy because he lied about an instant of self-harm. This left a scar, which connects him to another in the world beyond. In the corridor of time you can discover your ancestry and I bet that everyone watching, at least for a second, did wonder if perhaps Miyazaki found out something nobody else knew before, as if on a bird’s wing.

The curious heron bends over to slide into an opening in the attic. The old abandoned tower is irresistible and covered in legends galore. Did the mother’s uncle really lose his mind because he read too many books, as the servants claim? Or are the gigantic library and the collapsed bridge leading to it a lure to scout out the substance of existence?

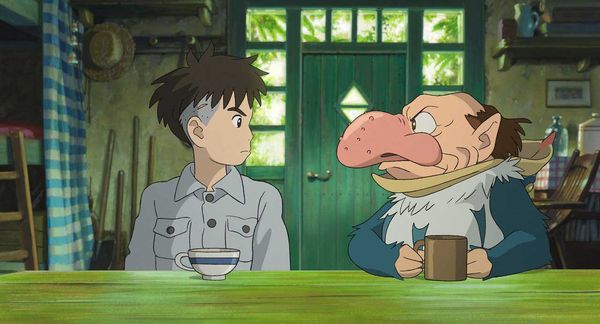

At the new school, the classmates bully Mahito and he gets into a fight with the farmer worker kids. But it is a self-inflicted injury that places the lonely boy on a new path. The big gray heron - you can hear his footsteps on the roof - it turns out, envelopes a man, who becomes the at times unreliable travel companion every good story needs. The Heron Man’s raspy voice, big teeth, and hybrid way of carrying himself make him one of Ghibli’s most distinctive creations.

Frogs climbing up on our hero are only the first animals who gang up in clans in this movie. Rudyard Kipling wrote that we cannot see the faces of our dead in dreams. If we believe him, then Mahito meeting his mother lying on a divan asleep must be a reality, as must the fact that she dissolves into water when he touches her. Sinking into a mosaic floor he learns that down is up and up is down.

Dark brown clouds hang over a ship at sea where big pirate vessels float about. You wouldn’t be surprised if the boat from Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things (a highlight of this year’s NYFF Main Slate) appeared on the horizon, complete with its chartreuse steam and illustrious passenger list. But no, a large gaggle of pelicans live on the shore among the ancient stones and pines and the Kafkaesque sign that warns “Those who seek knowledge shall die.”

A new pirate friend, the fisher woman Kiriko, bonds with Mahito over a shared scar and looks a little familiar in an Oz/Kansas kind of way. Little axolotl-like bubble creatures, called the Warawara need to be fed with fish guts so they can fly. And up they float “to be born” as we see spirals resembling the paintings of Hilma af Klint, were it not for the pelicans who feed on them. Not because they are evil but because they themselves are starving for a lack of fish. Himi, a girl whose power is fire, shelters an enigma.

No one manages to include urgent environmental concerns in quite so wonderous a way as Studio Ghibli productions do. From the flooding in Ponyo, all the way back to Isao Takahata’s 1994 Pom Poko, in which tanukis revolt the destruction of their habitat for the construction of a new development outside Tokyo, called Tama New Town (the setting of Yui Kiyohara’s terrific recent film Remembering Every Night).

The parakeets, green, yellow, pink and blue ones in The Boy And The Heron are rather human and grumpy with their armies, their determination, their election chaos. Grand Uncle, the builder of the tower where the journey began, lives in what looks like a De Chirico painting and taps a fragile column made from toy building bricks. Stones not stained with malice can create a world of beauty. Those dead and those alive share a world. A long hallway with many doors is the corridor of time that connects us all.

Miyazaki’s towers are built with uncommon stones, just remember Howl’s Moving Castle. A boy runs towards the fire not from it. The stepmother looks as beautiful as the mother, with lips the colour of clementines and a gentle demeanour and though terrified by her pregnancy, she becomes the next princess on his rescue list. Already in My Neighbour Totoro, a father and his two daughters move to the countryside and the girls’ exploration of their new environment opens up an enchanted world. So many of Miyazaki’s films share elements of Mahito’s journey, while everything here feels fresh and revelatory.

The hand-drawn beauty of the images always connects to ideas, something grander that we have yet to find out about. The flower pattern on the bed resembles propellors. The house, a great mix of classic Japanese and western styles, is as timelessly elegant as the boy’s gray suit with the two breast pockets and the pointy collar. He finds a book the mother left for her grown-up son, called How Do You Live? It is the title of a novel by Genzaburo Yoshino that Miyazaki was given by his mother when he was young, and it is the Japanese title of this movie.

Reviewed on: 02 Oct 2023