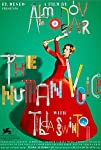

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Human Voice (2020) Film Review

The Human Voice

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

The most interesting aspect of Pedro Almodóvar’s The Human Voice (in the Spotlight programme of the New York Film Festival), starring Tilda Swinton, is her DVD collection. Or is it his? Douglas Sirk’s Written On The Wind and All That Heaven Allows, Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill (Volume 1 or 2), Blake Edwards’s Breakfast At Tiffany’s, Pablo Larraín’s Jackie, and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread - do they signal that what is to come is also a story of melodrama and revenge, loneliness and grief and powerful infatuation? Yes. On the bookshelves we see F Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is The Night and Almodóvar inspirations past (Alice Munro’s Too Much Happiness; three of her short stories became his Julieta) and future (he is working on an adaptation of A Manual For Cleaning Women by Lucia Berlin for 2022).

Swinton, always a strong presence, is stone-faced throughout as the woman at the centre of Almodóvar’s first film in English, “freely” based on Jean Cocteau’s 1930 play of the same name. Anna Magnani in Roberto Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948) was heartbreaking and yes, we live in different times, but the emotional impact is vital for this story. In the background we see yet another book, one on Ingrid Bergman, who played the classic Cocteau part for television. This 2020 short, shot in the times of COVID-19, is sorely out of step with its self-indulgence.

At times, I have mixed up the titles of the Henry James novella The Turn Of The Screw with Shakespeare’s The Taming Of The Shrew, or mistaken Richard Widmark for Joseph Cotten. I know, I know, they are nothing alike, but whenever one of them comes up, I have to think twice. I have confused La Voix Humaine with Bertolt Brecht’s powerful monologue of a woman on the phone, called The Jewish Wife, part of the production of Fear And Misery Of The Third Reich, which premiered in Paris in 1938. In Brecht’s one-act play, the woman packs her suitcase and plans her departure, to protect her husband, a doctor, from harassment by the Nazis. Cocteau’s The Human Voice, on the other hand, is a play about a woman being left by the man she loves and whom she had been with for years. He is getting married the next day to another. Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid dilemma (before Disney changed the ending so drastically) may come to mind.

Almodóvar’s own Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown from 1988 was already prompted by Cocteau’s play. The visuals at the start of this Human Voice are engaging enough, with Tilda walking on a soundstage, dressed in a beautiful long red crinolined dress. Then, garbed in black, she walks the other way. Two playing card queens in the same game. The opening credits are spelled out in the shape of tools. Now in a blue outfit, dog on leash, she buys an axe in a hardware store (the man behind the counter is Pedro’s producer brother Agustín Almodóvar, social distancing is key).

In the woman’s studio-built dollhouse of an apartment, colourful luxury reigns supreme. Never has a set seemed more hollow. While she talks on the phone to the never visible or audible man that got away, we see her rummaging through stuff. She may have been talking to herself, as far as we know. Then she smokes on the balcony.

The bathroom shots are wonders of product placement for lots of different Natura Bissé skin care products (i.e.: 1.7 oz. of the Diamond Extreme creme are $385, their intensive line minimising serum is $765 for 2 oz.). There are also some Chanel and Dr. Hauschka products. To make it less obvious? Speaking of it, Chanel even gets a verbal shout-out when the woman tries to convince the ex-lover to come in-person to pick up his things. “I put the letters in a little Chanel case,” she says and we cut to the case. The designer clothes by Chanel and Balenciaga and the like all look very nice on Swinton and we get the point quickly about her misery among the riches. And that is the problem with her performance.

She takes her red-knit ensemble out of the closet, then takes out the axe and chops up the man’s suit which was laid out on the bed. The lovely dog, Dash (the real star of the movie), lies down on the suit. He misses him. He prefers him to her, and judging by what we are seeing, so might we. The red Krups coffee maker, the spectacular shower, the colour-coordinated pills (5 yellow, 4 red, 5 medium-grey) signal nothing more than what the character named Old White Male would call Final Capitalism in Heinz Emigholz’s The Lobby, another film in the New York Film Festival consisting of a monologue, that takes a lot more risks than The Human Voice does.

When Almodóvar has the protagonist talk about kitchen knives and their temptation, all I could think of was the brand of knife he might choose to showcase. Tilda plays an actress and says sentences such as “women my age are fashionable again” and that the newfound popularity results from her “mixture of madness and melancholy.”

We hear that “reality always prevails”. Whose we might ask? More thought has gone into the selection of the separate pieces (which turtleneck? Which leather jacket?) of the final outfit Swinton picks from the closet than into what this film has to say to the majority of people making it through a pandemic. Arson and revenge are not exactly an original or empowered update on despair.

Reviewed on: 29 Sep 2020