Visions of Ecstasy

As new laws on “extreme porn” look set to expose inconsistencies in the UK’s approach to film censorship, Jane Fae spoke on behalf of Eye For Film to John Waters and Nigel Wingrove – two film-makers who have had their own quite singular difficulties with the film censors in the past.

This month, the UK is shifting the emphasis in its policing of “distasteful” material away from the publisher and beginning to place the burden of responsibility on to the shoulders of ordinary citizens.

This is because the government deems itself powerless to stop the flow of “internet filth” from abroad. It will therefore become a criminal offence merely to possess material that is pornographic, realistically depicts certain specific defined criteria (highly violent, necrophilia or bestiality), and grossly offensive to a jury. All of these elements need to be present – so a film that was merely “very violent” (mainstream productions such as Saw or Hostel spring to mind) would be unaffected.

Curiously, the government has added a caveat which says that material which has received a BBFC classification is wholly exempt from this Act – although extracts from any BBFC-rated films might not be. A Clockwork Orange is OK. Re-playing the rape scene from that film over and over is OK. But saving the rape scene as a stand-alone clip could see you up before the courts.

This does appear to create a serious trap for new and young film-makers. Before film is viewed by the BBFC, it is unrated. I spoke to the BBFC about this and they agreed that, in theory, this could cause problems. The BBFC rejects scenes that they deem to be obscene but, as they have no specific legal protections, they are still, technically, subject to the attentions of the police.

In practice, such action is virtually unthinkable. If the police started raiding the BBFC, the UK would soon find itself without a film classification body. This would be in no-one’s interests, least of all local councils’, who would suddenly be responsible for classifying every single film that might be shown in their cinemas. Chaos would ensue – and it would not be long before the government was forced to re-invent the BBFC.

Having said that, it is clear that such action has occasionally crossed the minds of the authorities. Back in 1997, the BBFC liberalised its approach to film censorship, and much stronger material began to enter the UK. Film Director and Chief Executive of Salvation Films, Nigel Wingrove, was at the Cannes Film Festival when he received a call telling him that Customs were raiding his London Offices.

Having said that, it is clear that such action has occasionally crossed the minds of the authorities. Back in 1997, the BBFC liberalised its approach to film censorship, and much stronger material began to enter the UK. Film Director and Chief Executive of Salvation Films, Nigel Wingrove, was at the Cannes Film Festival when he received a call telling him that Customs were raiding his London Offices.

On being told that the BBFC were operating a more relaxed regime, Customs responded that if material of the sort they had seized was sent directly to the BBFC, “they would have to raid the BBFC”.

Nigel is no stranger to this type of controversy – or to taking on the establishment. I met with him in the offices of Salvation Films, which describes itself as a “publisher of Euro cult, horror, giallo, erotic thrillers and sex videos and DVDs”.

Their website claims to “offer you every vice known to man and a few that aren’t”. My mind boggled, as I tried very hard to reconcile the well-spoken, insightful and yes, almost cuddly, Mr Wingrove with the horrid imagery that lined his office walls. Titles such as Emmanuelle And The Last Cannibals or Let Us Prey do not begin to do justice to the blood-spattered, gory and often sadistic content within. This is no place for the faint-hearted.

But then, that is probably the point. Nigel Wingrove works closely with the Satanic Sluts, an erotic burlesque act interested in exploring “areas of dark eroticism”. There is an element to his work that is both Goth and Gothic, and he is clearly fascinated by issues associated with the darker side of sex and religion. Vampires, demons, lesbians - and nuns - all feature heavily in Salvation Films' catalogue.

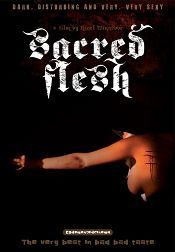

He still holds the dubious accolade of being producer to a film – Visions Of Ecstasy – that remains banned by the BBFC on grounds of blasphemy, although “the ban would almost certainly be lifted if I put it in for re-classification”, but there is little point: “it was a film of its time”.

Nigel claims his collision with authority came mostly from naivety. He started making films because "I wanted to develop the imagery I was creating photographically by making it move". His interest in strong themes guaranteed an inevitable clash with the authorities, and the early 1990s are a history of banned films, arguments with the BBFC and legal actions.

There is a definite sense, though, that he has put that era behind him. Salvation’s list is all BBFC rated: on the proposed new law, he talks of checking with his lawyers, and doing his best to comply. He sounds almost wistful. The attitude of the UK authorities, and their obsession with sex puzzles him. He has little time for pure violence, finding films such as Hostel actively distasteful; but he would not censor.

The US attitude feels much more healthy. There, a wealth of extreme views manage to co-exist side by side, and people are able to choose what to buy into – unlike the UK, which appears to prefer a uniform grey consensus, with the worst crime of all being the possibility that one person’s meat may turn out to be another’s offensive material.

The UK is definitely hung up about sexual imagery, in a way that it doesn’t seem to be about violence. When it first came out, The Story Of O created immense difficulties for the British film censors, whilst just across the channel in France, no-one batted an eyelid.

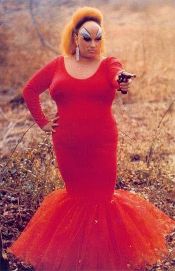

Nigel Wingrove's comments find an echo in the views of John Waters, to whom I also spoke just before Christmas. John’s work has been in areas very different from Nigel Wingrove's. However, he gained notoriety in the early 1970s for a series of what have been described as “transgressive cult films” - most notably, Pink Flamingos in 1972. Works such as Desperate Living confounded critics by mingling convicted criminals, well-known actors and porn stars in the same film. His cross-over to the mainstream was finally sealed with the release of Hairspray in 1988.

Nigel Wingrove's comments find an echo in the views of John Waters, to whom I also spoke just before Christmas. John’s work has been in areas very different from Nigel Wingrove's. However, he gained notoriety in the early 1970s for a series of what have been described as “transgressive cult films” - most notably, Pink Flamingos in 1972. Works such as Desperate Living confounded critics by mingling convicted criminals, well-known actors and porn stars in the same film. His cross-over to the mainstream was finally sealed with the release of Hairspray in 1988.

John is not averse to censorship. He is “wholly against kiddy porn”. There is stuff now available that he would definitely prefer was not out there: material that depicts real violence and abuse. He fears there is a market for genuine brutality, possibly even violence carried out to order.

However, when it comes to film, he draws a simple line between real violence – which he detests - and the stuff of fantasy. He says: “I can’t look at real stuff, even on the news”; but when it comes to films like Saw, he can deal with it.

He has had his own occasional run-ins with the MPAA, the US equivalent of the BBFC, most recently over their decision to award an adult-restricted (NC-17) rating to his 2004 film, A Dirty Shame. Although a comedy, based around the conceit of a war between sex addicts and “neuters” in suburban Baltimore, both the film’s plot and the MPAA’s reaction to it can be seen as encapsulating debates going on in the US right now over the limits to sexual diversity.

John Waters’ view is pretty straightforward. He says: "I don't care what people do in bed, or if they don't do anything. I just don't think that everybody else has to feel how you feel about it, whether it's sex, religion or politics."

That, for him, is pretty much the bottom line. He doesn’t resent the MPAA rating: he even reckons that back when he was getting started, the critical controversy over some of his films was actually helpful. “A certain audience would see that we had an X rating and that would be a reason for them to come and see the film.”

He, too, concludes that a part of the problem is the way in which rating authorities see sex and violence as different and, bizarrely, regard sex as the more dangerous of the two. “Rating Boards seem to be that much pickier where a film has explicit sexual content than where violence is concerned”.

His own innate sense of tolerance is somewhat tested by the idea of laws to criminalise possession of material. It takes a while to convince him that yes: this is what the UK authorities are proposing to do; have, in fact, already done. He is not impressed. It feels like the thin end of what could end up being a very large wedge.

But then, he has always found UK to be a little difficult when it comes to censorship. In the US, local standards mean that some places will throw up the occasional quirky result: but overall, there is no general attack on speech. By contrast, the UK continues to hold out against images that the rest of the world are prepeared to tolerate. For instance, we still ban the infamous “shit-eating” scene from Pink Flamingos.

But then, he has always found UK to be a little difficult when it comes to censorship. In the US, local standards mean that some places will throw up the occasional quirky result: but overall, there is no general attack on speech. By contrast, the UK continues to hold out against images that the rest of the world are prepeared to tolerate. For instance, we still ban the infamous “shit-eating” scene from Pink Flamingos.

Which brings us back to the new laws in the UK. Will they create problems for film-makers? In theory they do, because until a film receives that all-important BBFC classification, any scenes dealing with extreme sex could now constitute a criminal offence. However, none of the official film bodies we spoke to believed there was an issue. Not even PACT, which bills itself as the UK trade association that represents and promotes the commercial interests of independent film companies.

Either there isn’t a problem, or no-one is interested in the rights of people making “extreme films”. The trouble is, such legislation is pernicious, affecting us all. No-one seriously believes that from the day this new law becomes active, the police will start rounding up student film-makers.

However, anyone who works at the edgier edge of film-making will need to be careful. They will need to watch what they film and, in the end, make a choice over whether to play safe – which means working well inside the law, opting for certification, etc. – or take a risk. It will also put pressure on film-makers to go for classification. In the US, they have a name for it: “chilling effect”. We hope we are wrong: but the signs are that it is about to become a lot harder for new film-makers to test the boundaries.