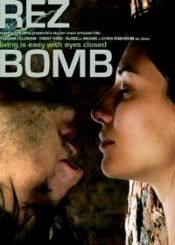

The tale of two young lovers out of their depth and on the run from a violent loan shark, Rez Bomb has proven a big hit with festival audiences but has yet to secure a UK release. It's set in the desperately poor community of Pine Ridge, a Lakota Sioux reservation, giving it a unique character. I caught up with director Steven Lewis Simpson to ask him what his plans are for the film and how he made it happen in the first place.

"The background and setting of the film are very important. I think it's important to let people know how desperate life is there, but I also want them to know what a powerful and different experience it was to make a film there with the people in that community. People there don't have much of a concept of time. The film production is all about time. I think it's quite extraordinary that people in the world are unaware of this. For example, a few weeks ago when Israel were bombing Gaza, I was seeing families being uprooted and made homeless and, you know, three or four families moving into one family's little concrete apartment, and I was thinking, the situation they're going into after they've been bombed is the equivalent of how most people already live in Pine Ridge.

"Unemployment is higher on the reservation than in Gaza and life expectancy is lower - and this is in the United States! So this film has provided a great opportunity to talk to the press and people in general and try to educate them about it, and about the prejudice that's still contributing to this situation. But at the same time, when any community is treated in that way, the people there find that they're being marginalised in every field, and that includes the entertainment business. To my knowledge, my film is the first universal story ever set there. I think that screams of how bad it is."

I note that I've only ever seen documentary films using this kind of setting before.

Steve agrees. "There have been a few feature films set on reservations over the last few years, but every single one is culturally specific. It's about the Indian experience. Half the time when Indian directors get money it's because people are saying 'Well, you can tell us your stories," kind of thing. That's what they want to see. For a whole community to never see themselves onscreen in something that they want to see - something entertaining - is extraordinary. I hope Rez Bomb will be a seed that starts some change there. I want it to be seen very much as a mainstream audience film, but it's very rewarding having First Nation people coming up to me and telling me how much they loved it.

"There are little pockets of stuff in there that are more specific to their experience, and they get it. There's a conversation that the heroine, Harmony, has with her boyfriend's mother, where she's asked what's with all the trash and why don't they just clean it all up, and that's easier to say when you live somewhere where they have garbage collection twice a week. I mean, there's truth on both sides of the argument, but nobody takes the time to empathise. I think mainstream audiences sometimes miss how subtle a lot of racism is. It's a discreet little question planted in the film that actually has a lot more behind it."

So how did he get involved in making a film in Pine Ridge?

So how did he get involved in making a film in Pine Ridge?

"It started in '99," he says. "I'd started out developing a script about the events that led up to the Wounded Knee massacre that happened at Pine Ridge in 1890, and in '99 I heard that there was a ghost shirt being returned from the Kelvingrove Museum [in Glasgow] that had been taken from the massacre site. On an impulse I decided to follow it. Within a couple of hours of reach the reservation I encountered Russell Means, who's in my film but who is also the most famous American Indian activist since Sitting Bull. He asked me to film three days of political meetings which they were doing there. So I was thrown right into the heart of the American Indian struggle.

"I went back over the years to film more - I have a documentary, a long term project, which is currently at a four hour cut and needing to be whittled down. That's one of my other Pine Ridge projects, but my features have to come first, and editing a documentary is an epic feat because you're writing it while you're cutting it. There's also a drama series that I really want to do, and there's another feature, which is more culturally specific. It's about events that took place around the time I was first out there, about a couple of uninvestigated murders. Pine Ridge is an extraordinary place for drama because drama is a way of life there.

"At the same time, I think a lot of people would go into that kind of world, as filmmakers, and do a Ken Loach style movie. That has its place, but the thing that strikes me is that nobody on a housing estate ever wants to see a Ken Loach movie. I want these people to be entertained."

Did his close involvement with the community help him to find the actors who played the minor roles in the film?

"It was pot luck a lot of the time! Arlette Loud Hawk, whom you mentioned in your review, I've known since 2000 or so. She's a good friend of mine. Hers was an important role, and most of the American Indian actresses whom I've seen onscreen lacked oomph - I wanted someone who felt real to me from the rez. Arlette has a lot of character and I felt she was believable as the mother. I've never seen photos of Arlette when she was young but I gather she was quite striking. Time really ravages people on the rez because of the poor diet and living conditions, but I thought some of the beauty still shone through.

"I basically just slotted Tamara Feldman, who plays Harmony, into a real family. The night before Arlette's first big scene, which was in the café, she stayed with us in the motel where we were based. Arlette and Tamara shared a bed that night and were up at six in the morning telling each other stories and bawling their eyes out. It was an extraordinary way for an actor and a non-actor to bond. Then, a few months after we were filming, Arlette developed cancer. Tamara went back on a number of occasions to help her through the chemo, and she survived. So for the actors it was a much deeper experience than most films. I think it had a profound effect of everyone."

What about the rest of the cast?

"It was extraordinarily random sometimes," Steve laughs. "For the father, we had a guy lined up who'd been in Dances With Wolves, but on the morning of filming he decided to flake out on us. He got his wife to phone up and when I asked if I could speak to him she said no, he was out feeding his buffalo. We were due to start filming in half an hour. So I went by the tyre store and saw a guy I knew there, and said, 'Hey - do you want to be in the film?' And he said 'Alright. When do you need me?' When he turned up an hour later I discovered that I preferred him to the guy who dropped out. As for Russell Means, he basically did it out of friendship, and I was thrilled because he's a pretty big name actor now.

"One of the proudest moments I had was when we had a screening at the Santa Fe festival and Russell came along, and he hadn't seen the film or read the script - he'd just read his own role - and he was really sweet. He said to the audience that it meant a lot to him to see contemporary Indians on the screen who weren't alcoholics or mystics or whatever. He used to be a hero of mine before I knew him, so to hear that from him was quite extraordinary."

"One of the proudest moments I had was when we had a screening at the Santa Fe festival and Russell came along, and he hadn't seen the film or read the script - he'd just read his own role - and he was really sweet. He said to the audience that it meant a lot to him to see contemporary Indians on the screen who weren't alcoholics or mystics or whatever. He used to be a hero of mine before I knew him, so to hear that from him was quite extraordinary."

I found that the actors brought a lot of humour and humanity to their roles. Steve agrees.

"I think if we'd hired all professional actors and flown them all in then they would have been focused on the experience of trying to relate to the horrible life on the reservation, but people who actually come from there have a lot of laughter. There are a lot of great characters and personalities. I didn't find I had to direct the non-actors very much at all, I just kept rolling. They talked through their scenes with the actors. Creatively, when I walked away from the production, I thought I'd probably underachieved, because so many things had been compromised on set, but when I started putting it together I was really pleased. I think that sometimes the faster you shoot the more energy you get through the camera."

That energy certainly comes across, but will viewers here get the chance to experience it for themselves? I ask how negotiations are going.

"I haven't been very aggressive with it yet," Steve concedes, "I'm just trying to build up a bit of a profile for the film. The market is really sharp at the moment. There are a couple of things on the table but they're not really that interesting. I'm also busy with a couple of other big projects at the moment. One's a remake of a previous film of mine, The Ticking Man, and it's been getting interest from some major players in L.A. What I do want to do with Rez Bomb, over the next few months, is tour it around the reservations as a way of getting it to the people there. That won't be a commercial endeavour, but I expect to find it rewarding."