|

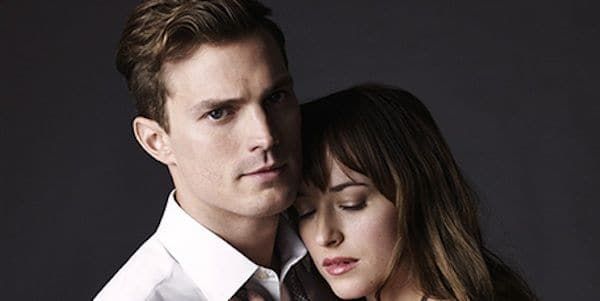

| Fifty Shades Of Grey |

Fifty Shades Of Grey is a slight and inconsequential film, made monstrous through notoriety. Positioning itself as the ultimate bdsm* love story for our time, it has achieved an odd double, simultaneously drawing the ire of feminists and fans of bdsm. Yet in the final analysis, this seems mostly misdirection – masterly or otherwise – encouraging heated social media debate on the grounds that no publicity is ever bad publicity.

Yet Fifty Shades is not the film imagined, but actually something much messier, more confused. It lacks coherence as any sort of bdsm manifesto: and it not so much flirts with themes of abuse, as writes them down and invites the world to buy them wholesale.

It doesn’t help that much critique is equally confused, seemingly written by individuals who don’t get out to the movies all that much or, if they do, have somewhat missed the point of how film works.

|

| Everybody loves beautiful things in Pretty Woman. |

The core problem in Fifty Shades is not so much the sex, which is largely female-friendly and unexceptional, as the central relationship between Christian Grey and “love interest” / object of desire Anastasia Steele. It starts with behaviour by him that is creepy, stalkerish and obsessive, turning up at her workplace, buying her an outrageously expensive car and generally inserting himself into her life in ways that are both controlling and non-consensual.

The problem with this critique is that this narrative is not the least bit unusual. It follows an arc commonplace to many “chick flicks” and rom coms. Boy meets girl. Boy pursues girl. Boy is overly pushy. Girl rejects boy, thereby setting up a second half resolution in which boy sees the light, understands that true love means letting go. Cue hearts and flowers and all things nice.

Reading such deconstructions, I am instantly reminded of Casablanca’s Captain Renault who, in the middle of Rick’s Casino, and collecting his winnings, utters the immortal line: “I'm shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here!”

Because this is romance. Or rather, this is how romance is sugar-coated and wrapped up in cute ribbons and sold to us. That is problematic, but it is scarcely unique to Fifty Shades.

Indeed, while many, myself included, have argued that 50 Shades owes much in plot and form to Pretty Woman, the central narrative is far older: this is Beauty And The Beast. Anastasia, the young virginal maiden is brought to the Beast’s lair where, eventually, her love and her pity will effect a magical transformation. The danger – the lie, perhaps – in this narrative is in the central premise: that beasts are redeemable; that they can learn to be less beastly, rather than simply hide their beastliness more effectively.

Outrage over Grey’s interpretation of romance as control is redoubled by reflection on his desire to impose what is broadly read as a contract for abuse. Not only is he treating Anastasia badly: he also wants to formalise this treatment by imposing a contract in which she accepts his right to micro-manage her life. This, too, is problematic, but perhaps not as some appear to believe it.

|

| "Although he had everything his heart desired, the prince was spoiled, selfish, and unkind" - Beauty And The Beast. |

Such contracts do exist within the bdsm sphere. If one grants that two individuals may freely enter into them – and I am aware that some don’t accept that – then they are not, in themselves, the issue. They become an issue where, as here, the contract is something that one party is attempting to force upon the other from a position of extreme power imbalance.

That is the essence of the abuse being concocted: Grey is wealthy, powerful, experienced. Steele is none of these. His attempt to force his will outrages equally feminist and bdsm sentiment.

Still, some critics have wrongly conflated the issue of the contract which, unless I missed it, is never actually signed, with Grey’s initial bad behaviour. The contract is never a done deal: is actually the heart of the film’s dramatic dilemma. He wants her to sign. She won’t. Will she? Won’t she? What does that mean, eventually, for their relationship?

And what does that say about him? Because in the end, this is part of the film’s central confusion. Grey claims, is claimed to be, experienced in bdsm. He is a dominant (not a sadist), who enjoys control. The entire point of his bdsm, he suggests, is the giving of pleasure and mutual satisfaction.

|

| As long as he needs me... I know where I must be. I'll cling on steadfastly... As long as he needs me - the doomed Nancy in Oliver!

|

This sits ill with the way in which he swings seemingly at random between power play, consistent with his initial claim, soft-end sensual bondage and, immediately prior to Steele’s rejection of him and all his works, vicious questionably consensual sadism. His bdsm consists mostly of a ragbag of incoherent habits drawn randomly from the body of kink.

Will the real Grey please stand up!

Throw in various comments by Grey about how he is “50 Shades of fucked up”, revelations of a past rooted in abuse and a present in which he considers himself not “normal”, and one can see why the bdsm community, too, is in revolt over this film.

Because this is not about bdsm. It is a bowdlerised version of the lifestyle made hostage to one of the oldest tropes in the film book: of the bdsm player as sick individual who will, in time, be redeemed and made whole again through the love of a good woman. Did I mention Beauty And The Beast?

Not only is Grey a confused bdsm’er: he is a seriously dangerous one, too. For while the actual play that takes place between him and Anastasia is mostly very mild, there is one reference – a running joke throughout the film – that has serious players very hot under the collar. This is the idea that cable ties, purchased from your local DIY store, are a mild and acceptable add-on to bdsm play.

|

| Tippi Hedren (Dakota Johnson's grandmother) is blackmailed into marriage in Marnie. |

No, no and no. A short sharp survey of half a dozen dominatrices provided instant consensus. Cable ties are dangerous, can lead to serious injury and used wrongly, may even be fatal. They are not for soft play but, as Ms Slide explained, there if you want something “harsh and brutal”.

Yet, in a statement that is likely further to incense the bdsm community, the British Board of Film Classification, which has been swift to pronounce on dangerous practices such as “face-sitting”, told me: “Fifty Shades Of Grey only features activities at the milder end of the bdsm spectrum and contains nothing that is likely to present any novel ideas or potential dangers to adults”. Did they take advice from any bdsm players before reaching that conclusion? The BBFC have since explained that they have "long-standing contact with bdsm practitioners" - though whether these contacts were consulted in this instance remains unclear.

In sum, there is little to recommend Fifty Shades. It is being written about because it is being written about and that, I suspect, was always the intention. It contains much that offends, much to dislike. But the themes that have kicked off so much criticism are commonplace to film, intrinsic to our view of what is acceptable in terms of romantic power dynamic and the behaviour of privileged males. There have been far more worrying films in the last 12 months: Before I Go To Sleep and Gone Girl for two.

There is much that is very worrying in the representation of women in film. And to focus so much concern on so small a film is to miss the point. Entirely.

* An umbrella term for bondage, domination, sadism/submission and masochism.