|

| Son Of Saul (Saul Fia) director László Nemes with Anne-Katrin Titze Photo: Sophie Gluck |

Claude Lanzmann's The Patagonian Hare, Shoah and The Last Of The Unjust, working with cinematographer Mátyás Erdély, the clothing choices of Edit Szücs, Stanley Kubrick's influence from Barry Lyndon to The Shining, the chaos of language and sound design by Tamás Zányi, were among the insights culled from my conversation with László Nemes on the making of his extraordinary, uncompromising film, Son Of Saul (Saul Fia), co-written with Clara Royer and starring Géza Röhrig.

|

| Danny Boyle with Géza Röhrig and László Nemes at the brunch for Steve Jobs Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

I caught up with the director in New York a couple of weeks before the US theatrical release and ran into him and Géza during the brunch for Danny Boyle's unorthodox take on Steve Jobs with Aaron Sorkin and Jeff Daniels, organized by Peggy Siegal, in The Vault of the St. Regis on Sunday. Michael Fassbender as Jobs suggests the machinations of his mind, mainly through interactions and in lightening quick flashbacks. Steve Jobs was the New York Film Festival's Centerpiece Gala selection.

Son Of Saul had its World Premiere at the Cannes Film Festival where it won the Grand Prix du Jury and the FIPRESCI Prize. László Nemes's debut feature has been chosen as Hungary's Oscar submission for Best Foreign Language Film.

In Son Of Saul, we follow closely Saul Ausländer [Röhrig], a member of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando, into Hell. He is a part of the crew of inmates forced to dispose of the corpses from gas chambers and crematoria. Saul, to whose back we are tied, the prison garb marked with an enormous blood-red X, finds a small boy still breathing underneath the dead bodies in the pretend shower - his son. Saul, triggered by this miracle in an inhumane place, tries to regain what it means to be human.

Anne-Katrin Titze: I would like to start with the disorientation you begin your film with. How did you balance not completely disorienting the audience and at the same time bringing us into a world that we don't understand? That nobody can really understand?

|

| Géza Röhrig as Saul Ausländer |

László Nemes: Well, I think it's twofold. First we have the main character who gives a point of reference. He is a guide throughout Hell. At the same time, what's going on in the context all around is changing and uncertain and that fluctuates. You know, the two things kind of work against each other. The sense of being lost and the constant reference point. As an audience we have to rely more on the main character.

We wanted to convey something about the human experience within the concentration camp, within the extermination process and that was our strategy. We achieved it through the mixture of chaos and organization. These two elements of chaos and organization are in the film, are in our strategy of directing and making it happen but also are at the heart of the human experience within the concentration camp.

AKT: Saul is our guide, but he is a guide we do not want as a guide at first. Then we accept him, because we have no choice.

LN: That's interesting.

Saul (Geza Rohrig)_225.jpg) |

| Oberscharführer Busch (Christian Harting) commanding Saul |

AKT: We are on his back, so close, far too close for any kind of comfort for the spectator. And you say - there's no other choice!

The camera gives audiences no comfort of distance and no choice as to whom we have to follow.

LN: These are very interesting questions I never get. I think, it's more an intuitive approach I have. I'm just thinking about it right now. The fact is, we need a guide through hell, there's no other way. We wanted to make this portrait of one man that gives the measure of everything. At the same time you cannot understand or decode or process but you have to accept that you're lost. It certainly creates frustration for the viewer but it had to be part of the experience.

AKT: At the very beginning you give a minimal intro into what Sonderkommando is.

LN: I think also, when you are in Auschwitz, there is no sign that you are in Auschwitz. You have to forget everything that was given to you by the films on the Holocaust. It has to be forgotten at some point because all those films rely to an extent on an external point of view. I really wanted to immerse the viewer in an experience that's not explained. It had to be visceral because that's the way it happened.

_225.jpg) |

| László Nemes with Géza Röhrig in The Vault of the St. Regis Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: You decide to give the protagonist the last name Ausländer [foreigner in German]. That is clearly also bringing us to the present.

LN: Why do you say that?

AKT: Well, he is a foreigner. Language and languages are very important in your film. "Pieces", "Stücke" [in reference to human bodies] is at the core of what is happening.

The sound design and the use of languages are as startling as the visuals.

LN: Auschwitz and the camps were about dehumanisation of the individual. In a way sticking to one person, gives back to the individual the human dimension that has been lost. So in a way we go against the logic of the camp even if we try to recreate the logic of the camp. There's an internal conflict in it. And the fact that he was named Ausländer - it was an intuitive choice. We were looking for a name that came from this region, the place from which my family came. And I like the fact that he is in a certain way a foreigner or a stranger. I think a lot of Jews were in a way.

AKT: How can you not be a foreigner in Auschwitz?

LN: Absolutely. You were talking about the languages. As an individual you have to be lost because of the language issue. Even if Yiddish was used throughout the camp whenever it could be used, you had this mixture, this chaos of languages, this Babel. And we wanted to have that - we have eight languages in the film, because we wanted something that is anchored in the very heart of the film. This sense of being lost, of being unable to communicate.

|

| Son Of Saul director László Nemes at the New York Film Festival Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: You show how language doesn't function any more. Just taking the example of Kaddish. We can't tell if the true/false rabbi even knows what he is talking about. There are these words in your film that function as pillars - one is "Stücke", one is "Kaddish", another one is "son." There is a construction with language, I thought.

LN: That is true. That is interesting. Yes, very important. Religion is losing its meaning, there is no more of that. At the same time, there is something very religious in what Saul tries to accomplish. In a way, Saul becomes a reference, even in a moral point of view. What interested me was having this saint man, even without knowing.

AKT [pulling out a book from my bag]: This is what I am reading at the moment, The Patagonian Hare, Claude Lanzmann's autobiography. Have you read it?

LN: Wow. Yeah, great.

AKT: He is talking about how incredibly difficult it was to get Shoah made. Did Claude Lanzmann see Son Of Saul? Did he comment on it?

LH: Yes, he likes it a lot. We became friends through the film. And I know he is very hard with fiction films.

|

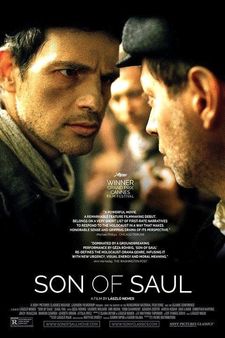

| Son Of Saul US poster |

AKT: Your film is almost on the other side of the spectrum but maybe that's where they can come together?

LH: In a way I think they are very much linked. We watched Shoah a lot before making this film. It inspired us. I think Shoah has a tremendous outer frame off stage. It's the vanished world of the Jews of Europe. The idea of an off-screen that is always there that fueled our approach.

AKT: Also looking at Lanzmann's latest film, The Last of the Unjust, and your approach to the "unjust" Sonderkommando - the guilt that is produced in the victims as part of the system.

LH: I think this film is also a reaction to that. There has been so much responsibility shifted back to the victims. At some point, from a moral standpoint, you have to separate. You don't make the victims morally responsible.

Coming up with László Nemes, working with cinematographer Mátyás Erdély, the garments by Edit Szücs, more on Claude Lanzmann, looking at the natural elements in Auschwitz, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Stanley Kubrick's abandoned Holocaust film and what's up next for the Son Of Saul director.

Son Of Saul screened earlier this year at the New York and London Film Festivals and will open in the US on December 18, 2015. The UK release is scheduled for April 1, 2016.

Géza Röhrig will participate in a post screening discussion with Anne-Katrin Titze during the opening weekend in New York at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas.